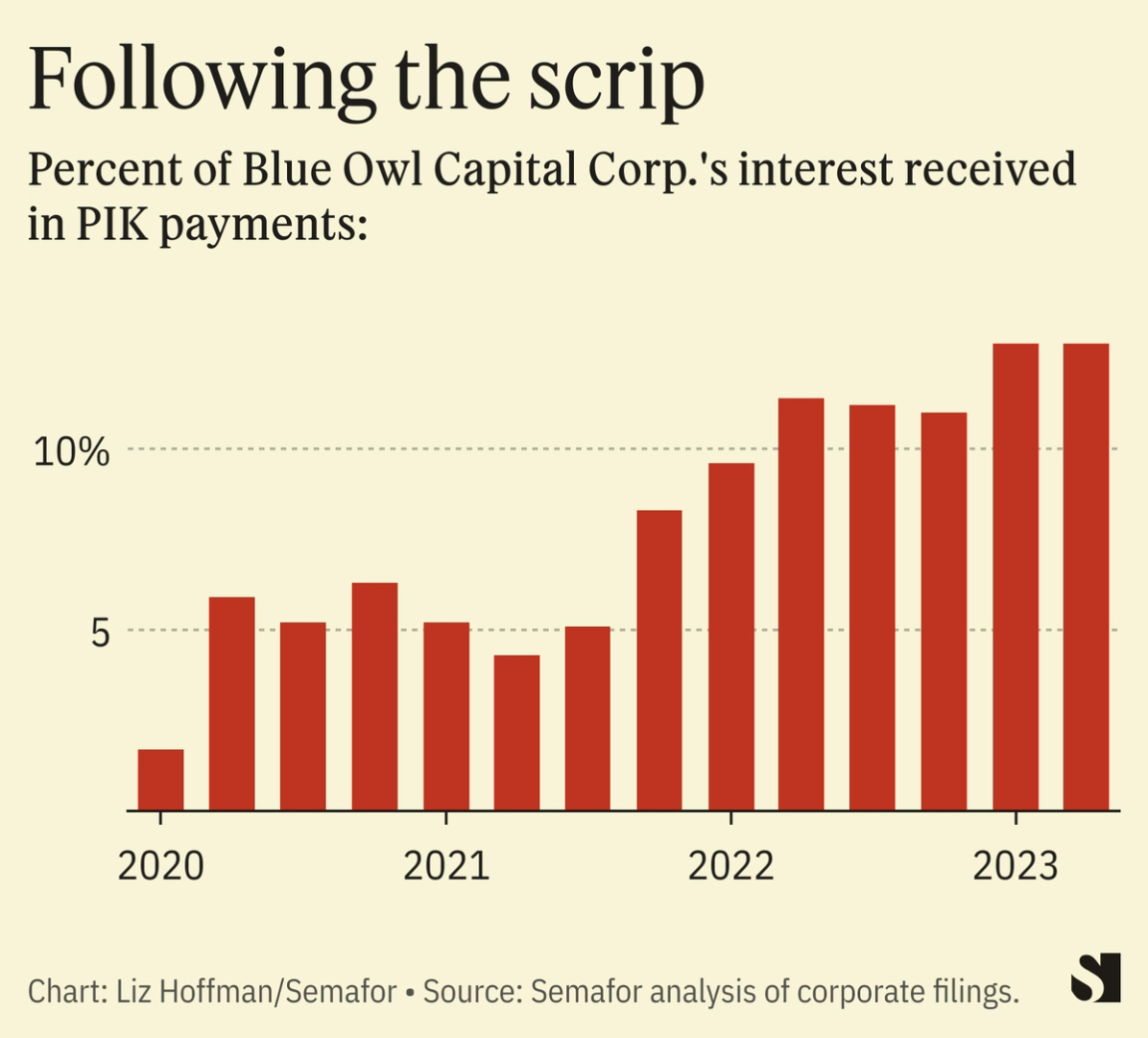

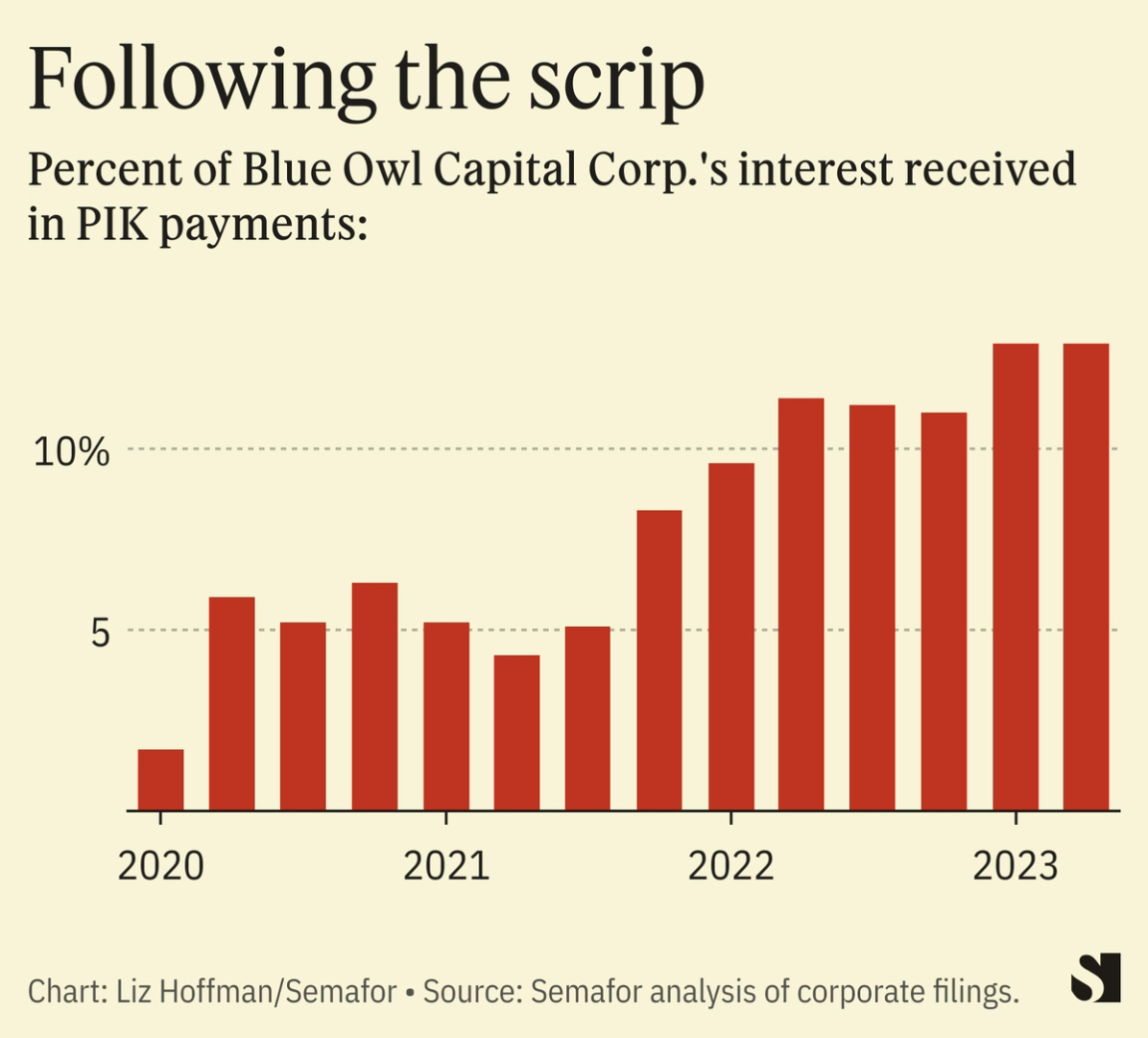

An addendum to last week’s story on the rise of “pray and delay” loan modifications. A refresher: Companies strapped for cash and facing looming maturities on their loans are asking their lenders for more time. It’s classic financial can-kicking and a consequence of rising interest rates. These deals buy time for companies, most of them private-equity-owned, to pay back their loans but raise the interest rate. They also — and this is important — often let borrowers pay that interest not in cash but in additional IOUs. That’s problematic in a bunch of ways that we meant to tell you about last week but did not: A typical case is that of Anchor Glass, which makes bottles for Heinz ketchup and Sam Adams beer. The company was sold to one private equity firm in 2014 and then another two years later, racking up cheap debt along the way. Last month it negotiated with lenders over a $710 million loan coming due in December that charged 8% interest. The new loan matures in 2025 and charges about 11%, and the company has the option to pay in scrip rather than cash. Such “pay in kind,” or PIK, options are getting more popular. The biggest nonbank lending fund, Blue Owl Capital Corp., got 13% of the interest payments owed to it in IOU slips last quarter rather than in cash, up from 2% in early 2020, according to its corporate filings. “It’s funny money,” says Howard Morris, a partner at law firm Morrison Foerster in London, who said he’s seeing it more and more these days. It also adds up quickly: “The exponential amount of debt when you do get to a formal restructuring is eye-watering.”  Funds like Blue Owl, which are called business development companies and given special tax breaks, are required to pay out 90% of their income — cash or not — to shareholders. So higher levels of in-kind payments can stress their own finances, and many close the gap by borrowing. The banks that lend BDCs money are also getting more leery of PIK options, said Carolyn Hastings, a partner at Bain Capital Credit. |