The Scoop

Australia’s Macquarie Group held talks to acquire Carlyle Group, a deal that would have created a new member of the $1 trillion asset-manager club.

The two firms discussed a transaction that would have instantly created a global investment giant across private equity, credit, real estate, and Macquarie’s legacy strength of infrastructure, people familiar with the matter said.

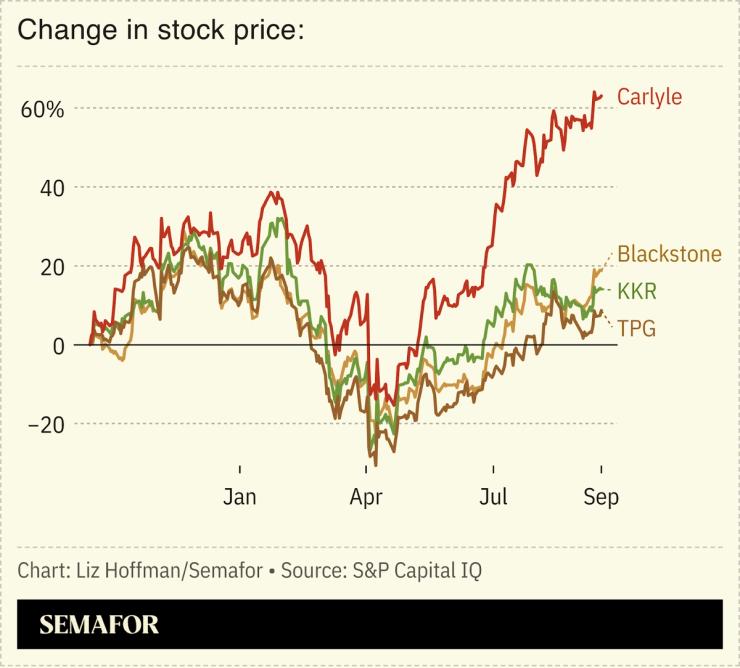

Talks fizzled this summer as CEO Harvey Schwartz’s turnaround plan caught on with investors, the people said. The Washington, DC-based firm’s shares have gained more than 60% over the past year, versus 17% for the S&P 500, and it’s now worth more than $24 billion. Macquarie, which also has a traditional retail and investment bank, is valued at $86 billion.

A combination would have leapfrogged private-capital firms including KKR and Ares in assets under management. Macquarie sold its public asset-management unit in April to Nomura for $1.8 billion, signaling its shift toward privates.

Representatives for Carlyle and Macquarie declined to comment. Carlyle co-founder David Rubenstein is an investor in Semafor.

In this article:

Step Back

The alternative asset-management world has been braced for a wave of tie-ups as size and global reach have come to matter at least as much as dealmaking skill. With more than 18,000 private funds on the road seeking a collective $3.3 trillion, there’s $1 available for every $3 being sought, Bain & Co. found in June — a ratio that has tripled since 2021. Better performance matters, but the race is increasingly one for reach, resonance, and distribution through private banks and retail funds, an area where Schwartz said on a recent earnings call that Carlyle’s 38-year track record helps.

BlackRock’s acquisitions of Global Infrastructure Partners and HPS, and Blue Owl’s acquisitions of Atalaya and IPI, and Ares Management’s purchase of GCP International are among transactions that have sent peers scrambling to find partners. Straight takeovers are hard to pull off; instead, there’s been a wave of partnerships like the recent tie-up between Goldman Sachs and T. Rowe Price, sealed with a $1 billion investment.

Liz’s view

There was a moment in 2022 where Carlyle looked ripe for a takeover. The acrimonious departure of CEO Kewsong Lee had sparked internal unrest, and the firm traded at a fraction of the value of peers that had branched out into credit, insurance, and infrastructure in big ways.

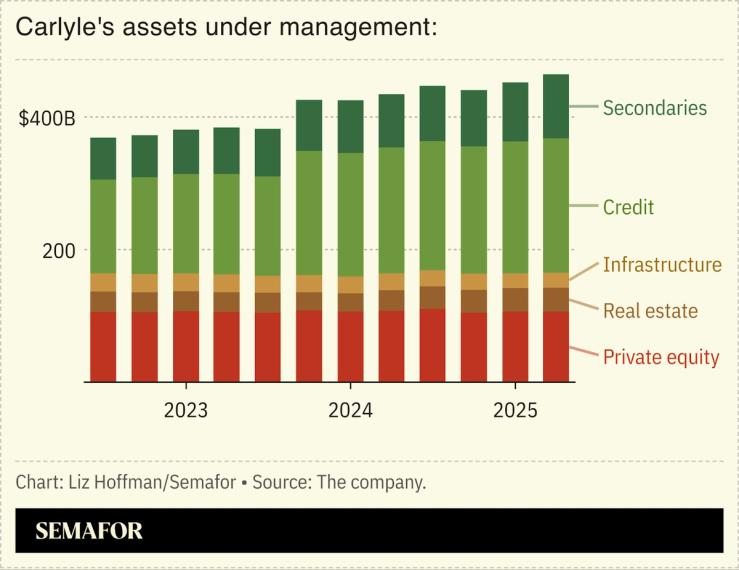

But investors, both public shareholders and fund investors, are buying what Schwartz, a longtime Goldman executive, is selling. It has raised $51 billion in new money over the past year, most of it in fast-growing credit and secondaries. Fee-related earnings have risen 56% over the past two years. And the firm has reestablished its Washington, DC roots and credibility, something Lee sought to downplay in his bid to dominate Wall Street on its turf.

Carlyle isn’t entirely fit for purpose in today’s investing world, but it’s getting there.

Room for Disagreement

Carlyle is still stuck in what Boston Consulting Group calls the industry’s mushy middle. Firms with between $300 billion and $500 billion of assets are competing with larger shops in trying to do it all, but spread their costs over a smaller fee base, the consulting firm wrote in April. They lack the specialization of smaller firms and the flywheel of giants. The magic of scale really starts to kick in at $1 trillion, which explains why KKR set a public bogey to get there by 2030.

Notable

- Asset-management mergers don’t always go smoothly, as Bloomberg’s deep dive on T. Rowe’s takeover of Oak Hill shows: “You can eat revenue, you can’t eat assets.”

- What could’ve been: Before HPS was sold to BlackRock, it held merger talks with CVC that illustrated the same tension as Macquarie and Carlyle’s flirtation.