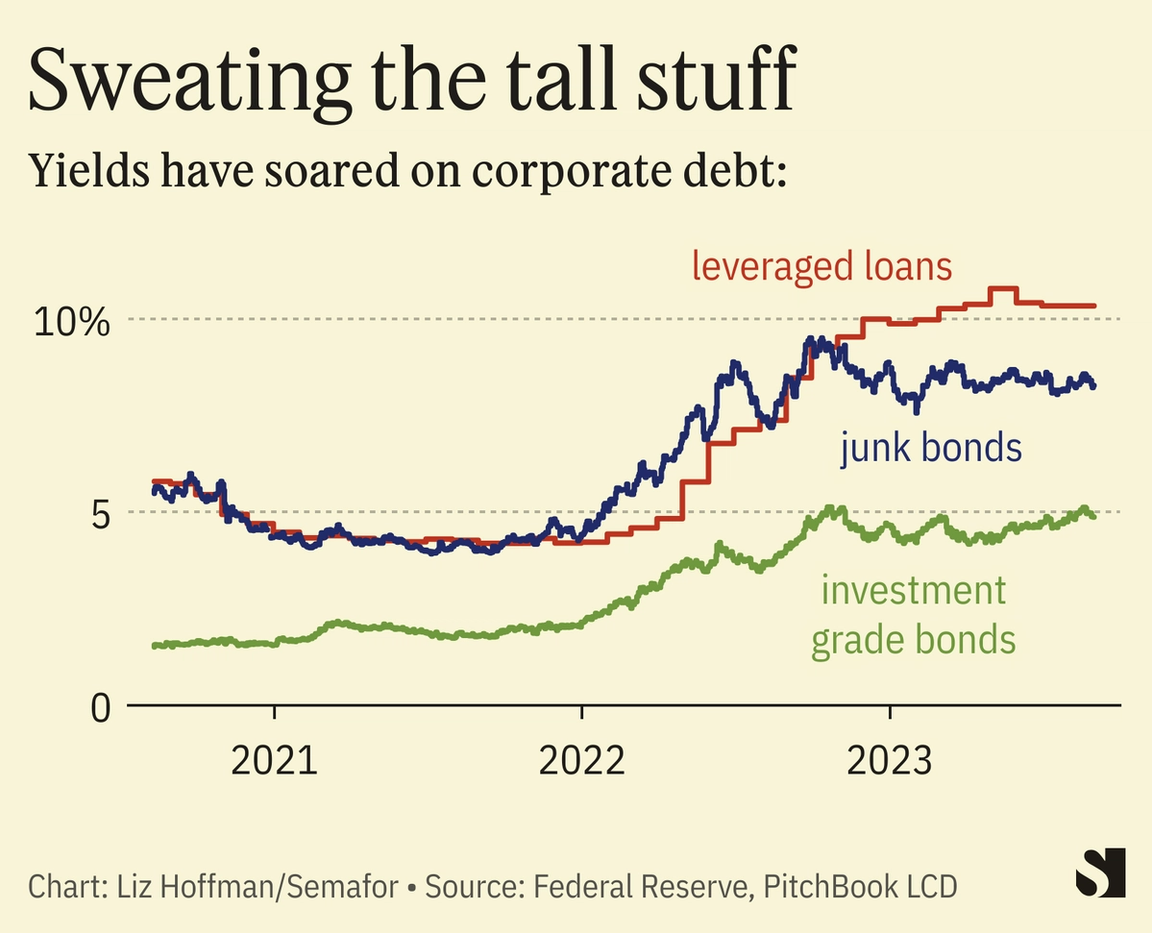

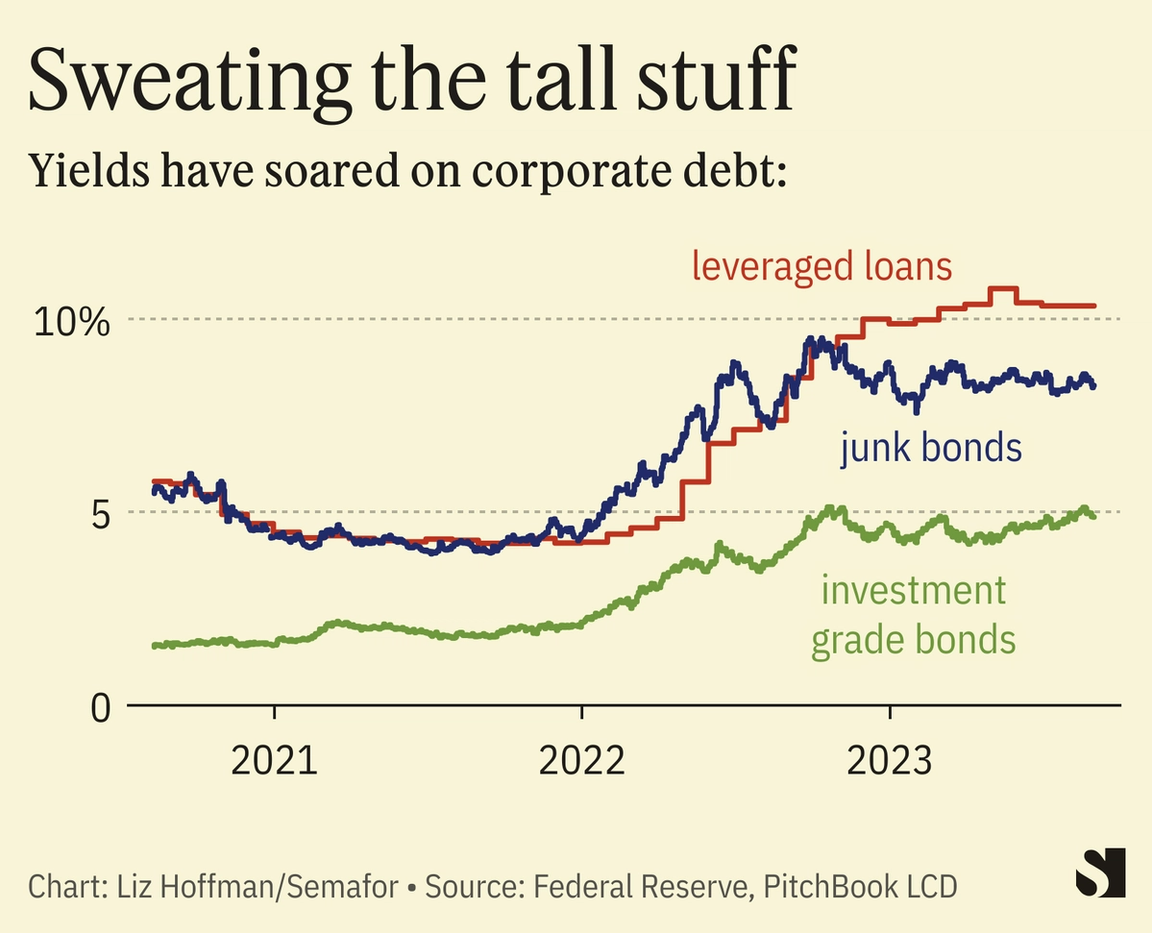

THE SCENE With debt payments soaring, companies and their lenders are returning to an old trick: kicking the can. Payback schedules have been extended on $114 billion worth of U.S. loans this year, most of them to companies with private-equity owners and low credit ratings, according to Pitchbook LCD. That’s the highest since 2009, when the country was emerging from a recession. These deals involve pushing out maturity dates by a few years and tossing lenders extra fees in exchange for their flexibility. The hope is that the company will be in better shape by then. Private-equity firms “are eternal optimists,” said Carolyn Hastings, a partner at Bain Capital Credit.  Soaring debt costs are one of the clearest ways that higher interest rates are rippling through the economy. Stressed companies lay off workers or delay initiatives: Goldman Sachs estimates that for each extra dollar of debt service, companies cut labor costs by 20 cents and physical investments by 10 cents. That’s how the Fed accomplishes its goal of cooling the economy. But in the meantime, companies that overborrowed during the last, halcyon decade are running into trouble. Blue-chip companies are paying more for debt than junk-rated companies were two years ago. Rates on risky loans used in buyouts have doubled since 2018, stretching companies that borrowed during a time of lower rates and rosier growth projections.  Lenders can, of course, wait until companies default and seize them, but banks and loan funds aren’t in the business of running billboard owners and dialysis clinics and scaffolding suppliers — all beneficiaries of reworked loans in the past few months. Operating businesses tend to deteriorate in creditors’ hands. “You don’t want to take the keys, but you are going to see more of that and more forced sales,” Hastings said. LIZ’S VIEW Debt amendments work when they bridge a company over a choppy spell. The best example is the pandemic, when lenders waived payments and covenants for borrowers from big corporations down to students. But this could get bad quickly. Companies bring money in from selling stuff, and send some of it out to service debt. A squeeze on either side can be problematic, but a squeeze on both is likely fatal. In 2009, revenues fell during an 18-month recession. But companies’ debt payments basically stayed the same or, if anything, decreased as the benchmark rate neared zero, where it would stay for a decade. This time around, the obvious problem is interest rates. Corporate loans are mostly floating-rate, so borrowers’ payments have gone up 11 times since the Federal Reserve began its hikes last year. Yesterday, the central bank projected rates would stay higher for longer. But recession risk still lurks, and while economists are increasingly optimistic, they say they won’t know for sure until 2024. Of 11 tightening cycles since 1965, seven have landed hard. A wall of risky corporate debt is coming due over the next two years: About $100 billion this year, $250 billion next year, and almost $400 billion in 2025, according to S&P Global. The credit market also looks different than it did in 2009. The risk once concentrated at the big banks has now been spread far and wide, with less oversight. Banks have to report their loan holdings to regulators, who look for sloppiness or dodgy marks. Private credit funds do not, and different firms often value the same loan at wildly different prices. If flexible lenders can float a company through peak interest rates, then it probably makes sense. But as Morris told me: “Sometimes it’s a sensible calculation that it’s going to take longer to realize value, and sometimes it’s just buying time,” he said. “We’re tipping toward the latter.” For Room for Disagreement and the rest of the story, read here.

|