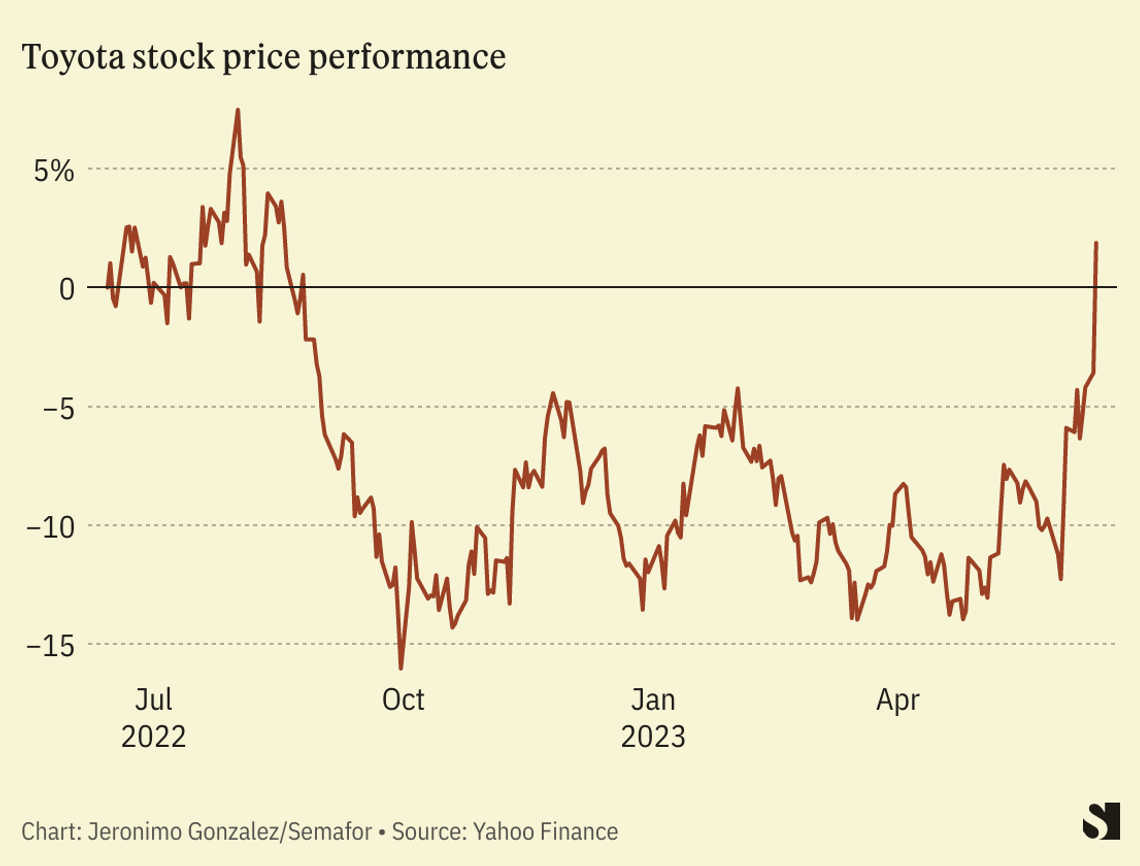

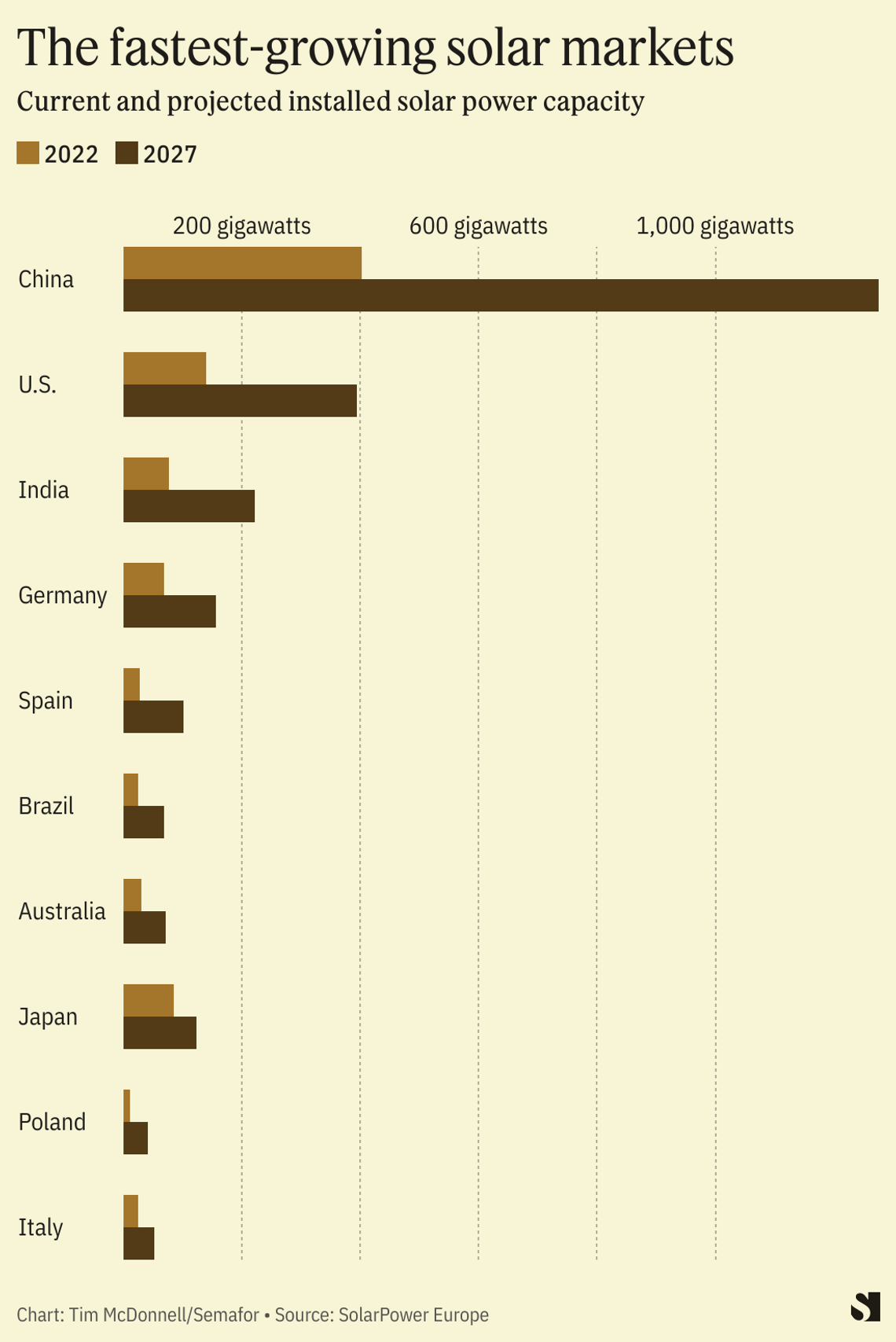

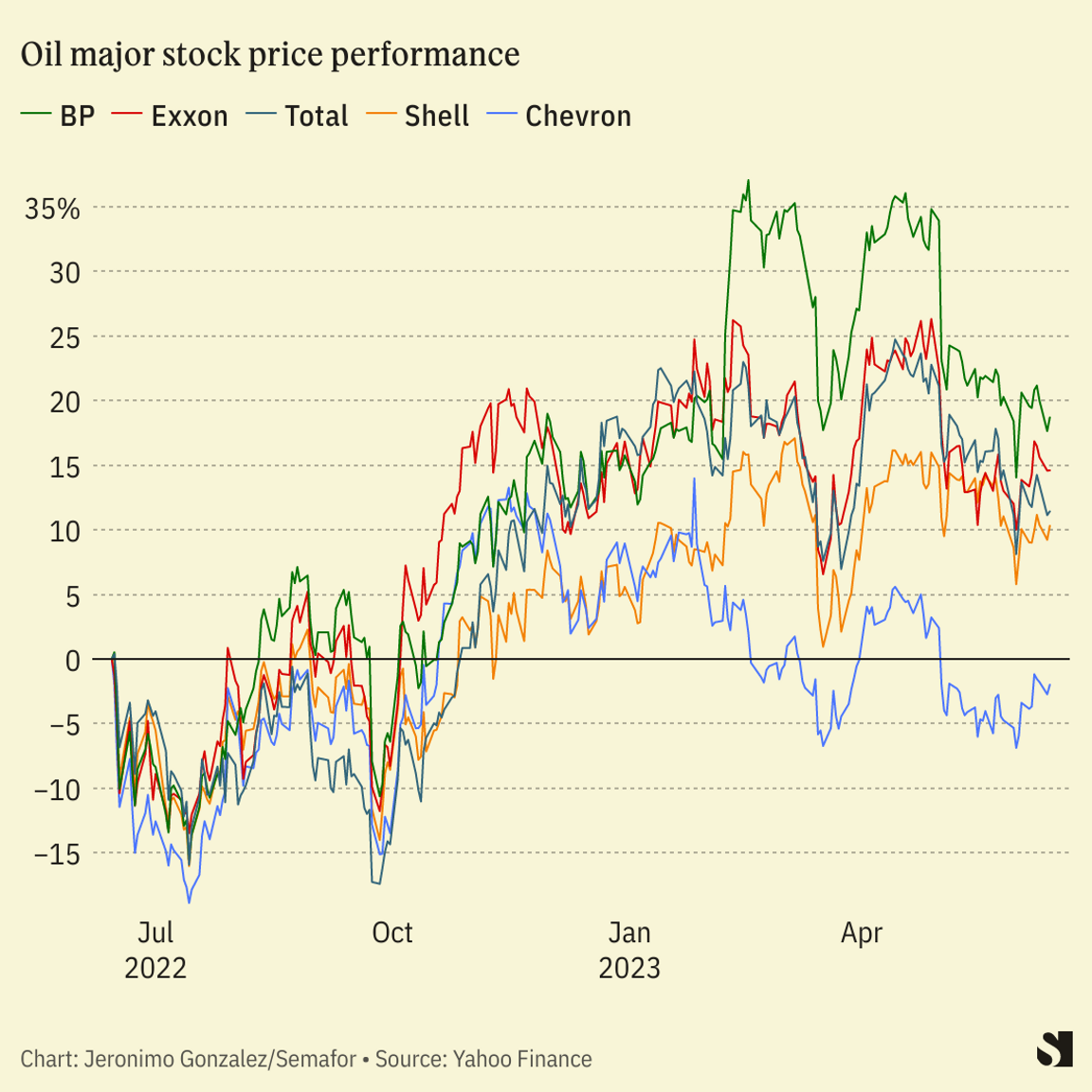

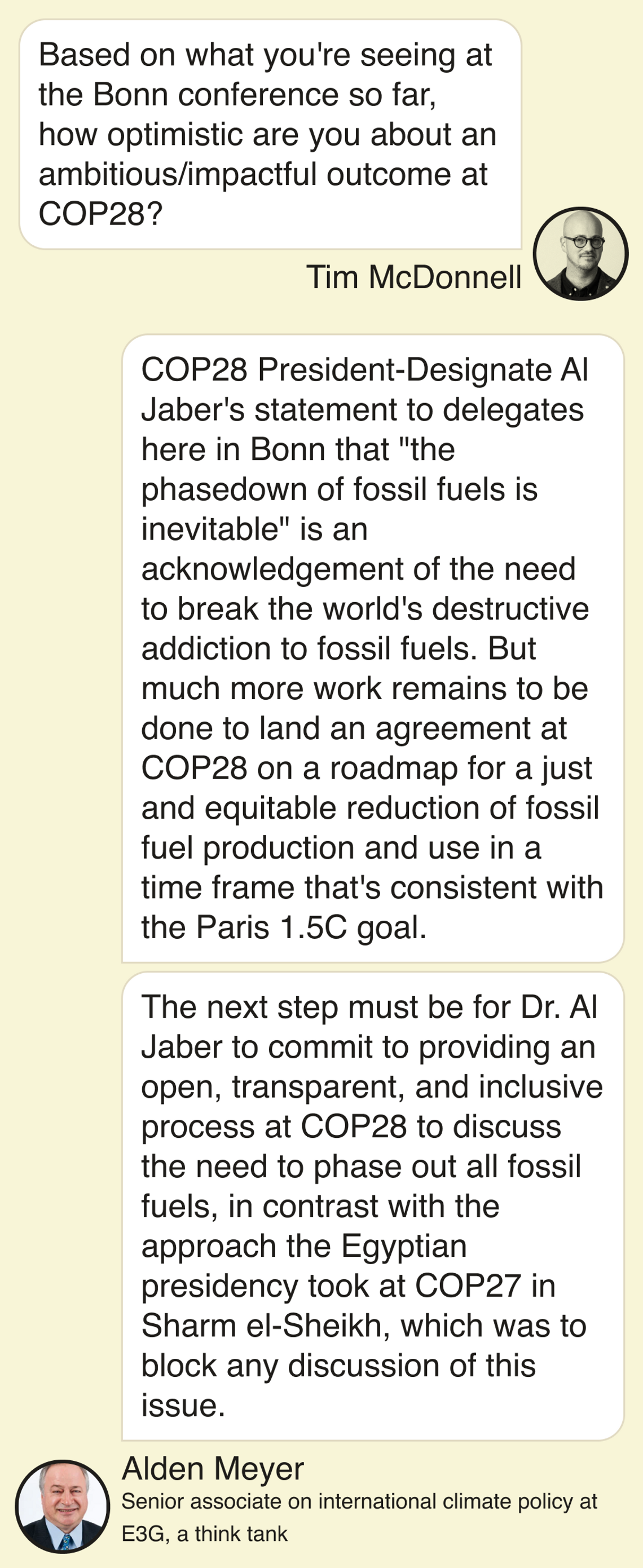

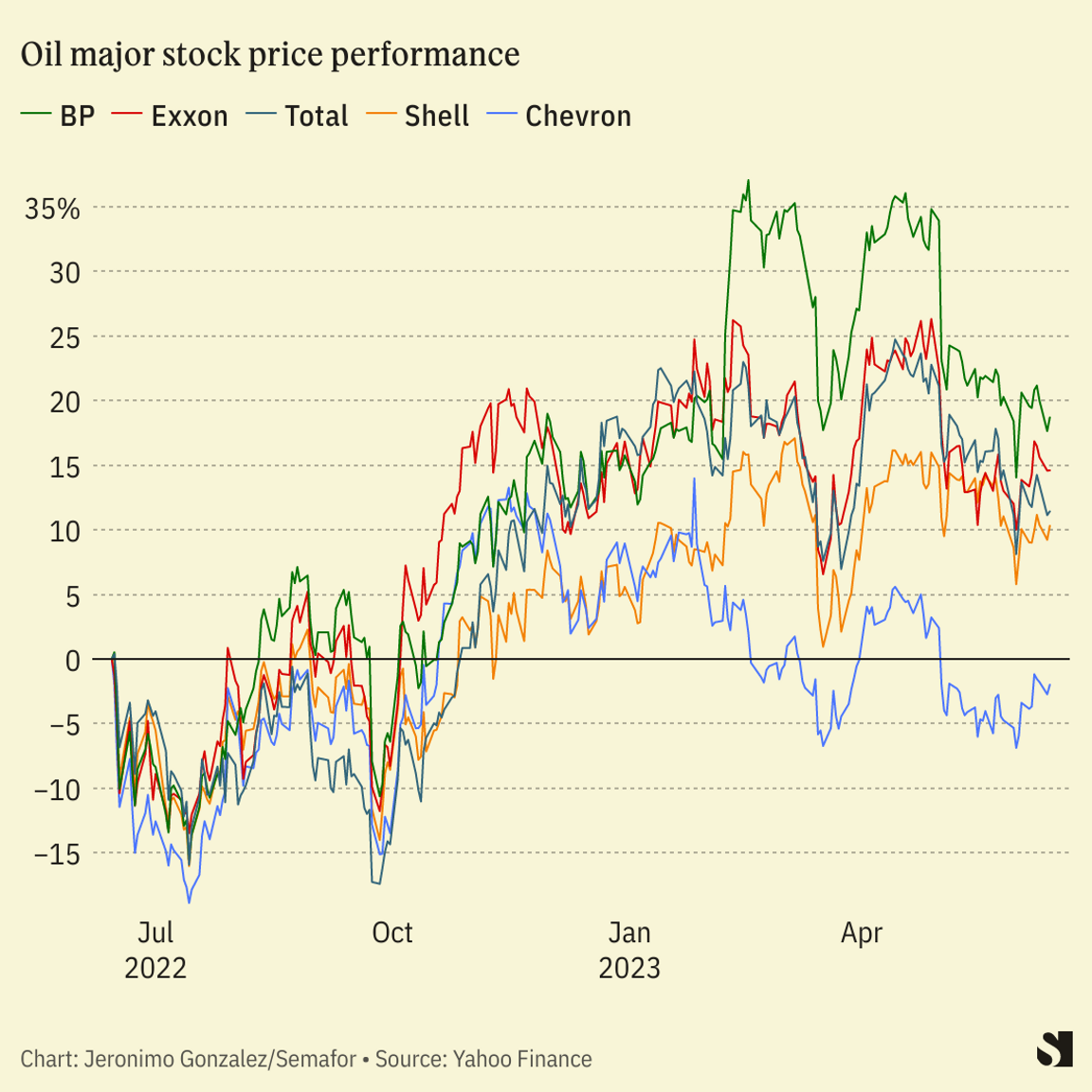

James Cornsilk for Semafor James Cornsilk for SemaforTHE NEWS The head of the International Energy Agency issued a stark warning to long-term investors, arguing against investing in international oil and gas companies because of mounting reputational risks and concerns that fossil fuel investments will soon become stranded assets. “I, myself, wouldn’t do it,” Fatih Birol said of whether he would invest his own personal pension in fossil fuel firms. KNOW MORE Birol also said governments worldwide were systematically underinvesting in electricity grids, which he labeled his “top concern” when it came to expanding renewable-energy capacity. “You built the most sophisticated car,” he said, “it is cheap, it is comfortable, it can drive very fast … but you forget to build the roads.” He blamed not simply delays over reforms to permitting — a major political issue in the U.S. right now — but also inadequate incentives and subsidies to make upgrading the grid financially attractive. Separately, the IEA chief called for negotiators at the COP28 climate talks this year in Dubai to target a doubling in energy efficiency, a tripling of renewables capacity, and for oil and gas companies to reduce their emissions from their operations and purchased energy by 60% by 2030. He also pressed for greater commitments from rich countries to help developing nations green their energy infrastructure. PRASHANT’S VIEW Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in particular has put a greater focus on energy security, particularly in Europe, where I live. But what energy security means is a thorny issue. Advocates of renewables argue it means countries and companies should invest more in wind and solar, which are less vulnerable to unstable suppliers, an argument that makes sense in the short and long-term. But Birol’s remarks underscore the challenge facing oil and gas companies, and why many are skeptical of their ability — or desire — to pivot from fossil fuels into renewables. In these companies’ view, energy security means a renewed focus on producing oil and gas to fill the void created by restrictions on Russia.  THE VIEW FROM DENMARK Just because oil and gas companies are risky doesn’t make their greener counterparts surefire bets. The poster child for transforming from a fossil-fuels firm to a renewables giant remains Orsted, now the world’s biggest offshore wind farm developer by gigawatt capacity. For one, the company is majority owned by the Danish state, which analysts say allows it to make longer-term investment decisions than publicly-listed fossil fuel companies. Orsted has also faced its own challenges: Its share price has more than halved since its peak in 2021, hit by increasing costs and rising interest rates, which affect renewables — funded by large upfront investments — more than fossil fuel projects. ROOM FOR DISAGREEMENT Investors have so far not punished oil and gas companies for failing to shift into renewables. Quite the contrary: European fossil fuel giants argue their share prices are undervalued compared to their American peers because of an outsized (if still minimal) focus on cleaner sources of energy. And at annual shareholder meetings last month, the vast majority of shareholder proposals urging ExxonMobil and Chevron to better report and cut their carbon emissions were overwhelmingly rejected. For more from Fatih Birol, click here. |