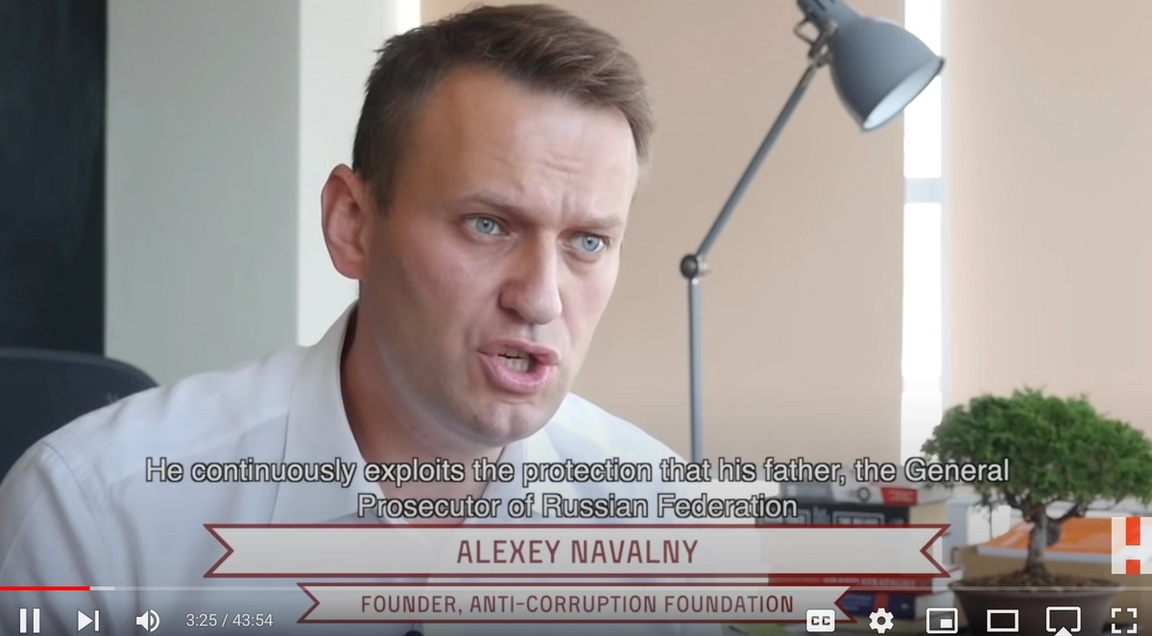

Matthew Prince was boarding a flight for Europe when he learned he’d been personally sanctioned by the Russian government. The CEO of Cloudflare, a cybersecurity company that started providing its services for free inside Ukraine last year, checked his itinerary to make sure he wasn’t flying anywhere near Russian airspace. I caught up with Prince this week about the digital frontlines of what he called the “first real war of the internet.” Q: What’s surprised you so far? A: The origin myth of the internet — it’s not really true, but that the U.S. government wanted something that could survive a war with Russia — has been proven kind of true here. The internet in Ukraine has been more resilient than anyone expected. Even as fiber has been cut, packages continue to find a way out, and information from the West continues to get in. A lot of that is traffic on Starlink, which grew 500% from mid-March to mid-May and another 300% by November. This is the first real war of the internet, and the internet has proven to be very resilient. Q: That’s an interesting phrase. I think a lot of us had expected this to be a faster, quieter, more digital war, but instead we’re watching footage of tanks slogging through the countryside. What do you mean? A: Look at Kherson. As Russia took control [in March 2022], they rerouted internet access back through Russia, where it was subject to Russian censorship. That has since switched back. We could almost track in real time who was in control of the core data center. We’ve never seen that before in open warfare.  Cloudflare CloudflareSecond, the internet has allowed the stories of what’s happening to get out in a way that’s raw and unfiltered. If Russia had been able to turn the internet off, I’m not sure Zelenskyy or Ukraine would have survived. Instead he’s been beaming into conferences and posting on TikTok. Q: It helps that he’s very good at the internet. A: Very good at the internet! Q: Why haven’t we seen Russia’s hackers be more aggressive against Ukraine’s allies in the West? A: I don’t entirely know. We’ve seen some attacks that appear to be Russian against Poland and Japan, interestingly, and some against Germany and the U.K., but very little aimed at the U.S. And what we have seen doesn’t look like a concerted government effort. I think part of it is that it’s a zero-sum game. If you’re attacking one target, you’re not attacking somewhere else. Attacks on Ukrainian infrastructure have increased dramatically, focused on government administration, financial services, and media.  And here’s maybe an anecdotal point: Before the war, a lot of the big cyber gangs were Russians and Ukrainians working together, and they have now splintered. The Ukrainian members of the largest, Conti, released all of its secrets, making it effectively impossible for the Russian side to continue to operate. Q: What are you watching for in the months ahead? A: Whether Moscow shuts down more of the internet inside Russia. [Putin critics] Bellingcat and Navalny’s [Anti-Corruption Foundation] put a lot of their content on YouTube. The Kremlin could block YouTube but it hasn’t.  YouTube YouTubeCompare that to China, which never let the horse out of the barn. The Chinese internet was filtered from day one and the government, with a lot of careful foresight, trickled access out. Russia, Iran, and other authoritarian regimes are now trying to figure out if they can get the horse back in. |