The Scene

The Peet’s Coffee executives were fed up. The coffee roaster had spent years trying to expand its foothold in single-serve pods and gotten nowhere as Keurig, the industry’s leader of what consumers generically now call K-Cups, choked off its access to key distributors.

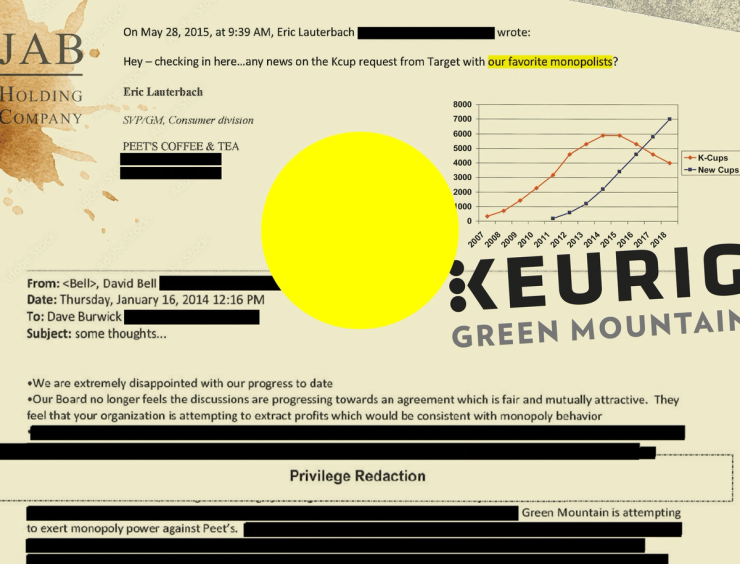

“Our favorite monopolists,” a senior Peet’s executive complained to colleagues in a 2015 email.

Now Keurig’s efforts to maintain iron-fisted control of the coffee-pod market after its patent expired in 2012 are the subject of an ongoing private antitrust lawsuit that the company’s pending $18 billion takeover of Peet’s has given new relevance. The deal would create a global coffee giant and bring one of Keurig’s biggest customers in-house — the type of vertical integration that competition experts have long warned against, and a deal whose consequences, critics warn, will be measured out with nickels, dimes, and coffee spoons in every grimy office kitchen in America.

Efforts by one plaintiff, an independent San Francisco roaster, to press its case in a November letter to Trump’s antitrust regulators appear to have failed: The deadline for the Federal Trade Commission to seek additional information from Keurig and Peet’s — a sign the agency might seek to block the deal — expired without any such requests, people familiar with the matter said.

But the case is winding slowly toward a trial anyway, as grocery prices become a deepening pain point for Americans and the Trump administration balances competing antitrust impulses. A traditional Republican light-touch approach has come up against a populist faction skeptical of corporate power. Perceptions that antitrust enforcement has been politicized have rankled top Justice Department officials.

San Francisco Bay Coffee, that independent roaster, is seeking about $450 million in damages. Another plaintiff, TreeHouse, sees enough value in its claims that its recent sale to a private equity firm includes a sweetener of up to $1.9 billion if the lawsuit breaks its way.

This story is based on internal emails, strategy memos, and financial analyses included in a decade of court filings reviewed by Semafor, and interviews with people involved on both sides of the dispute. They show how Keurig leaned on wholesale distributors so they’d refuse to carry pods from third-party manufacturers — making it difficult, as Peet’s found, for competing coffee brands to reach customers.

Keurig also added invisible ink scanners to its countertop machines, a feature it billed as a safety measure and a way to brew more nuanced beverages. But when asked by a marketing executive in 2013, ahead of the new machines’ launch, whether the change would do “something special,” the company’s senior director of K-cup systems wrote back: “IT WILL DO NOTHING TO BENEFIT THE CONSUMER.”

That same week, another top marketing executive wrote to colleagues: “I continue to question the cost, functionality and consumer benefit of squid,” the company’s code name for the new ink-reading capability.

Keurig said the upgrade was meant to build a broader menu of coffees, teas, and other beverages. It scrapped the ink reader in models sold after 2017, in part because it didn’t reliably work.

“We believe this lawsuit is without merit, and we continue to defend against it vigorously in court,” Keurig Dr Pepper said in a statement. “Consumers have had and continue to have a wide variety of coffee options, both within the innovative Keurig system and beyond, and we are confident that we will reach a favorable outcome on this matter.”

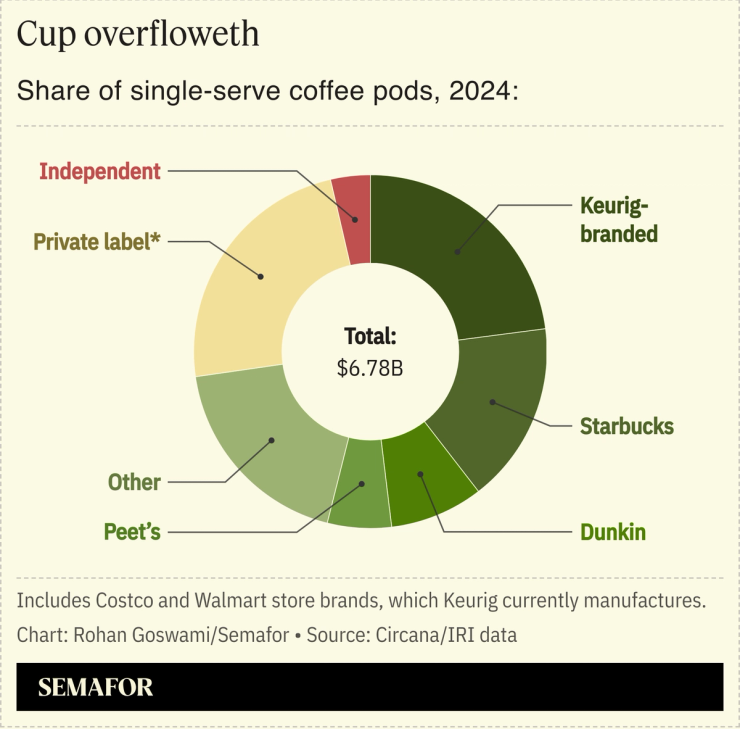

In 2024 Keurig controlled more than 80% of the pod market, executives have said. Its own branded pods represent about one in every four sold, and those it manufactures for other brands, including Starbucks, Dunkin, and Peet’s, make up another two in four. It also makes pods for Costco’s and Walmart’s respective store brands, though data on those is harder to come by.

Step Back

Keurig developed K-Cups in the late 1990s, and by 2011 they accounted for two-thirds of the company’s $2.6 billion in sales. The company lost money on each countertop machine but made up for it with pod sales, following the lock-in model so crucial to the razor industry.

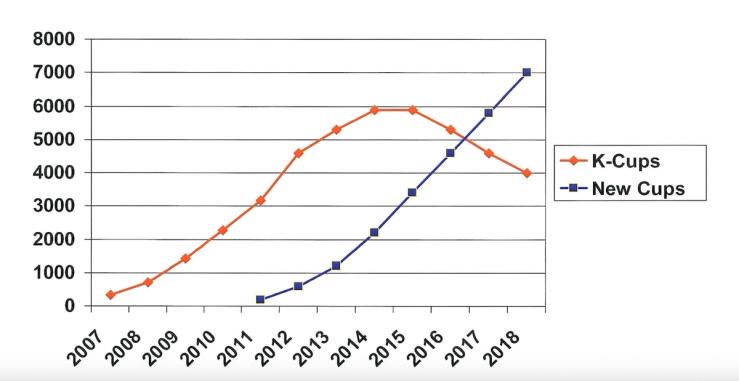

As it faced the expiration of its patent in 2012, internal estimates showed the company expected that third-party pods would overtake its own K-Cups within five years. Each lost percentage point would cost Keurig $35 million in annual revenue, according to a presentation by company executives to its board.

“Multiple technologies can discourage competition,” Keurig’s president had written in a presentation to the company’s board. Keurig “must avoid becoming an open system.”

A consultant hired by Keurig to come up with ways to protect its edge acknowledged in 2012 that efforts to “lock-in” pods “is against competition law.” “That’s why they invited their lawyer to meet,” the consultant added, appearing to refer to the inclusion of counsel in a strategy session, “to give ‘privileged’ status to the meeting.”

He added: “Delete this email please.”

Know More

Peet’s had outsourced the manufacturing of its pods to a Keurig competitor and used a distributor, Vistar, to stock them in offices around the country — the original market for single-serve coffee, before it caught on at home. After Vistar signed an exclusive deal in 2013 to distribute only Keurig pods, Peet’s scrambled to assemble a new distributor network. The company gave up on that effort a year later and hired Keurig to manufacture its pods, despite higher costs.

A senior executive explained the decision in an email to the company’s auditors: “We were completely shut out,” he wrote. “Major distributors such as Vistar and Aramark told us at senior levels that they would not jeopardize their relationships with Keurig to support Peet’s despite clear customer interest.”

Two years later, Eric Lauterbach, a Peet’s executive who would later become its CEO, sent the email calling Keurig “our favorite monopolists.” Lauterbach announced his departure in November, three months after Peet’s agreed to sell itself to Keurig.

By 2014, unlicensed pods had gone from less than 2% market share to more than 15%. But they have shrunk since 2015 and are at less than 5% today, according to industry sales figures.