The News

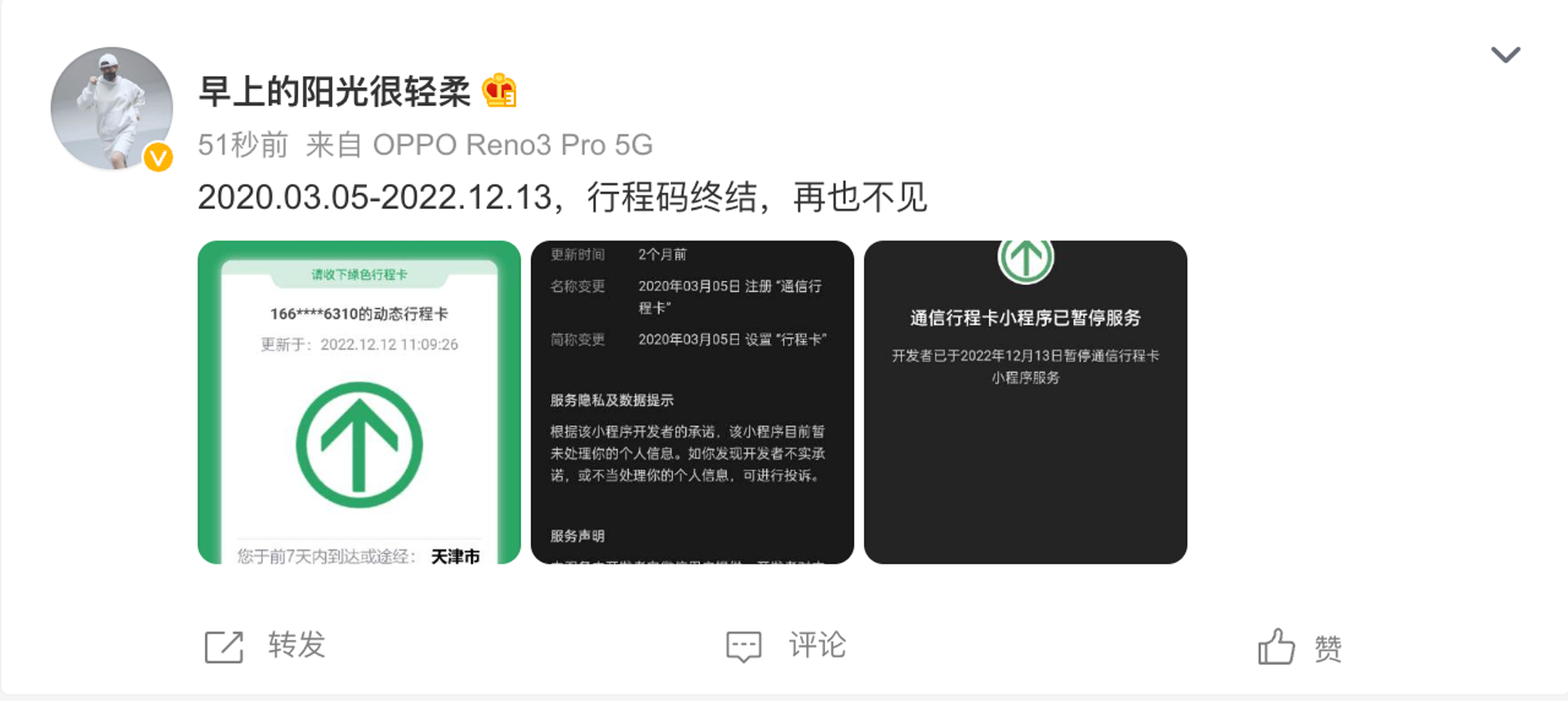

Chinese social media users posted their final screenshots of a nationwide COVID location tracking app after the government announced Monday that it was deactivating the once-mandatory service.

Many citizens on Weibo posted celebratory messages hailing the end of the Tongxin Xincheng Card travel tracking app (通信行程卡), which had been used since 2020 to determine whether residents had been in high-risk areas in order to decide their testing and quarantine requirements.

Some, however, acknowledged the app’s utility which had been a critical part of China’s zero-COVID strategy.

China’s ambassador to the U.S. told Semafor’s Africa Summit Monday that COVID rules would be “further relaxed” in the near future and travel to China would get easier.

Know More

Since 2020, Chinese authorities had partnered with the country’s three biggest telecommunications companies to gather data on people’s movements.

On Monday, officials announced that the service would be taken offline and that everyone’s travel history would disappear by midnight.

“It’s been three years and I’ll never see you again,” one Weibo user wrote.

“I hope I’ll never see you again,” another person wrote.

Some users appeared excited over the prospect of international travel, with one woman writing: “Does this mean we can go wherever we want to play?”

Other felt a bit more nostalgic.

“Thank you for protecting our country,” one verified user wrote. “I will never hear the phrase ‘please show your health code’ in the future.”

While the national tracking app has been scrapped, many other similar health code tracking apps continue to operate locally in cities and provinces.

Step Back

China recently announced that it would relax quarantine and testing requirements, among other measures, as part of a nationwide shift away from the country’s stringent COVID restrictions. The decision by authorities came shortly after China was gripped with protests calling for an end to zero-COVID.

But the country has also seen a dramatic uptick in cases — with some cities also reporting a shortage of resources.

According to the Wall Street Journal, emergency requests in the capital city of Beijing had jumped from an average of 5,000 to 30,000 a day — straining the capacity of paramedics.

A video circulating on Chinese social media last week purported to show a huge crowd jostling inside a Beijing hospital.

Notable

Kendra Schaefer of Trivium, a policy research organization in China, suggested in a Twitter thread that the end of the Tongxin app “doesn’t actually change much” in terms of how the government uses data.

She said that even though the app is gone, the “data is still there” and implied that it could be reutilized for other government applications.