The News

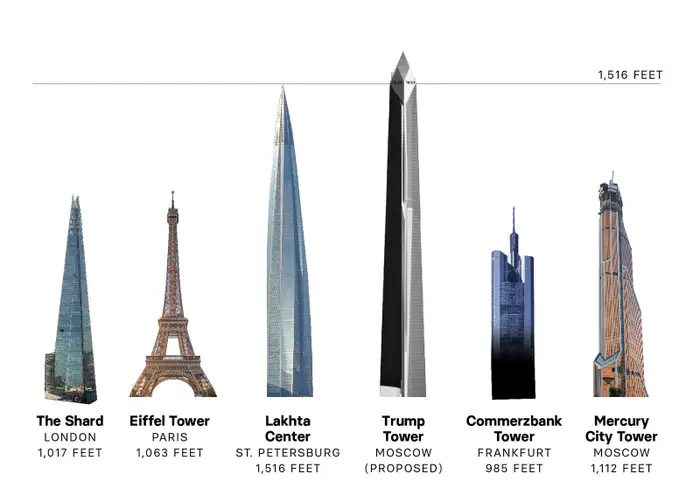

Does anyone remember the Trump Moscow Tower? The glass obelisk would have been the tallest building in Europe, had Donald Trump’s aides managed to get the deal done in the campaign summer of 2016. As a sweetener, the Trump Organization discussed gifting Russian President Vladimir Putin a $60 million penthouse.

The deal provided a non-conspiratorial explanation for then-candidate Trump’s friendly attitude toward the Russian leader — but by the time Jason Leopold and Anthony Cormier broke the story for BuzzFeed News in 2018, nobody wanted a new theory about Trump.

The building never went up. War and politics get in the way of real estate projects. But I’ve always thought of the episode as a reminder of both the allure and futility of big Russian deals for Trump and many other Americans. And as soon as Trump returned to office this January, the chatter again rippled through the hapless world of would-be Russia investors that there might be some business to be done.

Now, The Wall Street Journal has revealed that negotiations between Trump envoy Steve Witkoff and Putin’s sovereign wealth fund chief, Kirill Dmitriev, have interwoven talk of transactions and business opportunities.

“Russia has so many vast resources, vast expanses of land,” Witkoff told the Journal, outlining a scenario in which Russia, Ukraine and the US would “become business partners.”

This framework has been met with deep skepticism by veterans of the last wave of optimism about trade with Russia.

“You show up and you meet Kirill Dimitriev, and he seems so reasonable, and he has nice suits and he’s trotting out all these statistics, and you’re like, ‘Wow, how could they have missed this brilliant opportunity, they must have been blind for 30 years,’” sighed one banker deeply involved in Russian investments. “It’s the greater fool theory. People who have been around Russia for a while — they know how hard it is.”

Bill Browder, once the biggest foreign investor in Russia and now a bitter Putin critic, told me it’s “the stupidest thing ever to think the Russians will let Americans get a single penny out of this.”

There are two reasons.

First: politics. Are investors willing to bet that a decades-long project can survive Putin’s imperial ambitions and shifts in American politics after Trump?

Second: the actual history of Russian treatment of US investors. The 1990s saw a seedy and glamorous “Wild East” depiction of American businessmen profiting in a dissolute and corrupt Moscow. Their investments were mostly more colorful than material, though some Western traders made personal fortunes.

But even before Russia and the US reverted to Cold War-style hostility, major US oil investments in Russia were scarcer than is commonly assumed. Only two major American-sponsored projects in Russia ever became profitable, and both were signed in 1995. Conoco got out of the Polar Lights investment in 2014, when Russia invaded Crimea. ExxonMobil wrote off $4.6 billion in its Sakhalin-1 investment in 2022, though Russia has opened the door to a return.

A person familiar with talks between ExxonMobil and its Russian counterparts said they’ve focused on “finding ways to recoup losses associated with expropriation.” Exxon’s CEO, Darren Woods, has said the company has no plans to return to Russia.

The opportunities that remain are substantially less glamorous. Companies selling everything from iPhones or oilfield service equipment can get back into the Russia trade without much risk. Traders with big appetites for risk can jump into the market for deeply discounted Russian distressed debt.

And then there’s a third category, the one the Russians are currently dangling: medium-sized sweetheart deals.

“There are a number of discrete business opportunities that the Kremlin could make available to a friendly Western business-person — anywhere from real estate development deals to relatively small-scale natural resource deals,” said the banker. These projects are possible, he said, “if you have the right partner and dedicate immense time and effort to stop yourself from getting fleeced.”

In this article:

Ben’s view

The optimism about exporting American democracy alongside Western capitalism in the early 1990s has long since curdled into another reality: The US and Europe didn’t export democracy to Russia. Instead, the West (London in particular) imported Russian corruption. The Europeans were always ahead on this — less idealistic about changing the Russian system, and quicker to capitalize on the strategic and material deals that eluded American investors. The Nord Stream pipelines, which kept German energy prices low and German politics pro-Russian, were the crown jewels.

One pipeline was blown up in a wild Ukrainian operation that’s the subject of Bojan Pancevski’s forthcoming book The Nord Stream Conspiracy. But most foreign investments in Russia have ended without underwater explosives — in forced sales to local investors. The yogurt company Danone, which was among the longest to hold on, sold its Russian assets last year to a businessman linked to the Chechen strongman Ramzan Kadyrov; the company lost $1.4 billion on the deal.

The result was “a generational transfer of wealth from American shareholders to these others,” a founding board member of the American Chamber of Commerce in Russia told Charles Hecker for his timely new book Zero Sum: The Arc of International Business in Russia.

And while Hecker told me there’s an appetite among some American companies to return, they’d face a new Russian business elite operating in a new commercial and legal landscape. Permissive Russian pharmaceutical regulations, for instance, mean the country is awash in counterfeit GLP-1s.

So if there’s a bull case for investing in Russia, it’s this: Pessimistic American veterans of Moscow may understand that Russia is the same tough place. But they may not realize how much the US has changed, and how eager this administration is to make the Nord Stream-style deals Europe now regrets.

Room for Disagreement

“We believe that the US and Russia can cooperate basically on everything in the Arctic,” Dmitriev told the Journal. “If a solution is found in Ukraine, US economic cooperation can be a foundation for our relationship going forward.”

Notable

- Sanctions have forced Russian oil companies to sell off assets, and US investors are looking to buy Lukoil’s international operations after the US Treasury derailed a sale to the trading firm Gunvor by calling it the Kremlin’s “puppet.”

- Energy investors betting on Trump see opportunities in Venezuela, Shelby Talcott reported for Semafor.