The News

The energy transition is losing steam, two new reports conclude, shifting the conversation likely to dominate the upcoming COP30 summit from how to avert climate change, to how to survive it.

A UN analysis this week of countries’ formal climate plans revealed two unsettling facts: First, that only 61 countries, covering about one-third of global emissions, have submitted new carbon-cutting plans this year as required by the Paris Agreement; China, the EU, and other major emitters aren’t on that list. Second, if those plans are fulfilled, they will deliver less than 6% of the emissions reductions needed by 2035 to limit global warming to 1.5°C. As UN Secretary General António Guterres said last week, “overshooting [the 1.5°C target] is now inevitable.”

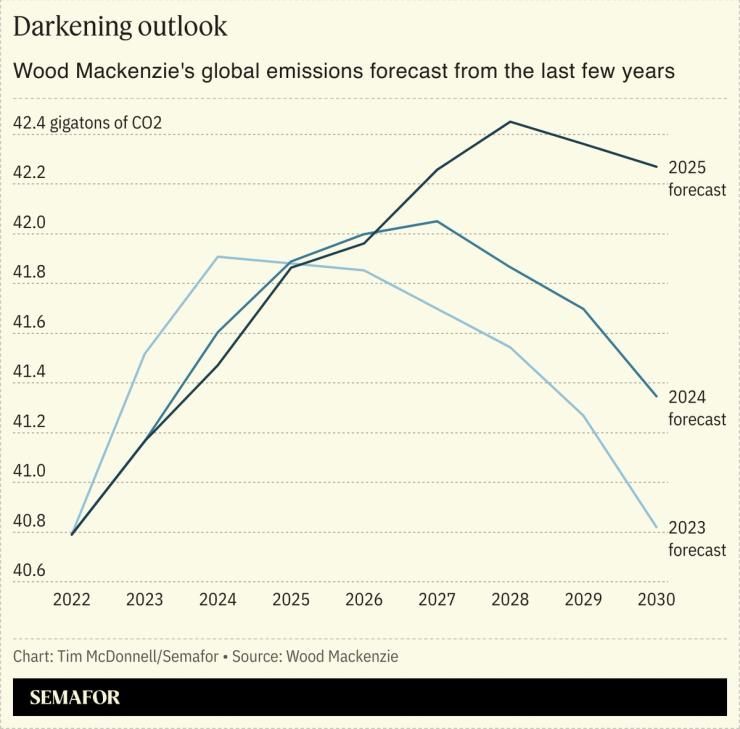

Separately, a report by energy data firm Wood Mackenzie concludes that wars in Ukraine and the Middle East, supply chain bottlenecks, and the Trump administration’s campaign of trade wars are all working to slow the transition from fossil fuels to cleaner energy sources. WoodMac projects global emissions in 2030 to be 4% higher now than it did two years ago, and has pushed out by several years its expected date for peak global oil demand. “It is widely acknowledged that the world will not achieve net-zero emissions by 2050,” chief analyst Simon Flowers wrote.

In this article:

Tim’s view

COP30, which will kick off next week in Brazil and continue for the following two weeks, already had a daunting task to make any meaningful progress with the US again withdrawn from the process. A decade after the Paris Agreement set the ground rules for global cooperation on climate, it’s clear that the process is neither totally ineffective nor capable of delivering the kind of rapid, sweeping change envisioned.

Just two years ago, the oil executive leading the Dubai COP secured a commitment for the global energy system to “transition away from fossil fuels.” That prospect now seems less realistic than ever. The recent defeat of an international plan to tax emissions from shipping showed that the willingness of governments to collaborate on punitive emissions reductions is waning, especially in the face of a pressure campaign by the Trump administration to encourage more, not less, fossil fuel use. Even Bill Gates, a onetime stalwart champion of climate action, said this week that near-term emissions targets are a distraction at best and could even be counterproductive for human welfare.

In that context, there’s not much that can be credibly achieved at COP30 to tamp down the main causes of climate change. Better prospects for a more productive dialogue will be around how to deal with the consequences.

“We will see adaptation and resilience really at the center, because we just can’t avoid the question of impacts anymore,” David Waskow, director of the World Resources Institute’s International Climate Initiative, told Semafor.

But that conversation won’t be easy either. Foreign aid funding, never in surplus, is especially limited since the Trump administration dismantled USAID, and many rich countries are choosing defense and other priorities over climate aid. Developing countries currently receive less than one-tenth of what they need to manage climate impacts, the UN reported this week, a “yawning gap” that shows no signs of closing. But the summit’s Brazilian leaders have promised a new “package” of resources for adaptation from rich countries, philanthropies, and development banks.

Room for Disagreement

While new commitments to end fossil fuel use may be lacking, COP30 could see tangible progress on another key source of emissions, deforestation, which Brazil plans to target through a new $125 billion fund that will pay tropical countries for forest conservation.

It’s also likely that COP30 will show progress on the adoption of renewables, even if those are for now mostly additional to, rather than a replacement for, fossil fuels. China, Indonesia, and other Asian countries are committing to massive increases in solar and wind adoption, and renewable energy lobbyists will be present in force in Brazil to make their case to government officials there.

“Now [COP] is all about the real economy, that’s where the real action is happening,” Sonia Dunlop, CEO of the Global Solar Council, told Semafor. “What’s happening outside the negotiations is almost more important than what happens inside.”

Notable

Hurricane Melissa, currently ravaging the Caribbean, is a perfect example of why climate adaptation finance is so badly needed. The International Monetary Fund estimates that the region requires at least $100 billion in new investments to manage its new environmental conditions.