The News

Alternative economic data is trickling in to fill the blind spots created by the suspension of data collection during the government shutdown, and the broader doubts over the reliability of numbers put out by bureaucrats pressured by President Donald Trump to paint a sunny picture. But the substitutes are all over the map.

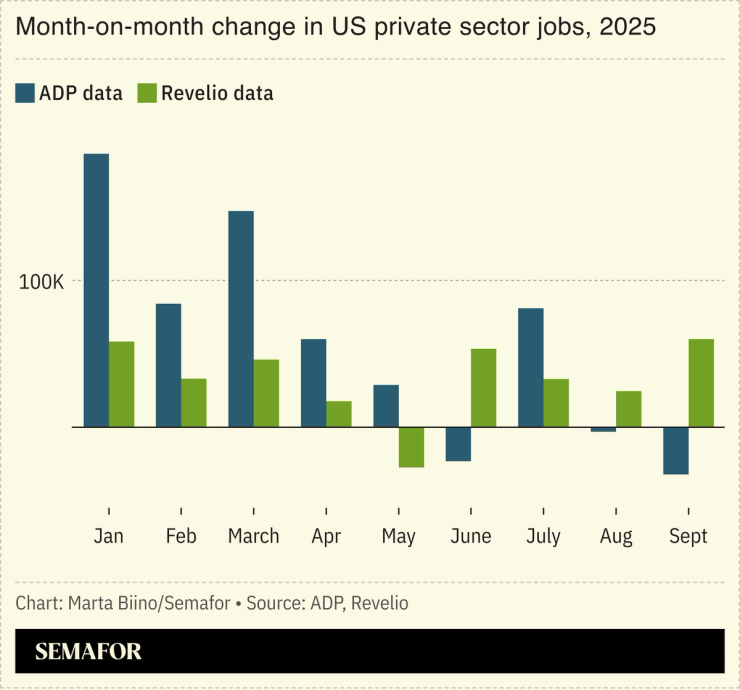

Private investment firm Carlyle’s new jobs report, pulled from its 277 portfolio companies with 730,000 employees, shows the US added just 17,000 jobs in September. Payroll giant ADP says private companies cut 32,000 jobs last month, while Revelio, which scrapes online profiles and job postings, estimated a gain of more than 60,000. Meanwhile, the Chicago Fed’s new unemployment tracker “indicates some steadiness in the labor market,” the regional Fed’s president, Austan Goolsbee, said.

Liz’s view

Carlyle’s entry into the economic-data fray is notable for another reason. Private-equity portfolios were once too disconnected from the broader economy to offer a read-through; common stock in highly leveraged companies can only say so much about the economy as a whole, which depends more on credit than stock prices, no matter what headlines you read.

But private capital’s growth into new sectors and credit give a wider window that’s now worth peeking through.

“The size of the portfolio, that’s number one,” Carlyle’s chief economist, Jason Thomas, tells me. “And second, when you have control positions or significant influence in companies, you get access to a lot more information — order books, backlogs, prices paid, prices received, headcount.”

That’s data that public-company shareholders, to say nothing of bondholders, could only dream of. It’s also more detailed than anything the government has.

The chunk of the economy in private hands has raised some concerns for policymakers, who worry they can’t tell what’s happening. One solution is to nudge companies back into the public markets by reducing the burden. Another would be forcing more disclosure at private companies; Washington has tried this a bit in the context of combatting money-laundering and terrorist financing, though not yet for financial bills of health.

A third, though, is to embrace that huge swaths of the economy are, and will be, private, and for more firms like Carlyle to realize it’s in their interest — and ours — to know what’s going on there. What has lived as a secret sauce inside Carlyle for more than a decade might now inform policymakers flying blind.

“You look back over the past five years, and [our data] is mapping right on top of actual GDP,” with some statistical fixes to correct for sectors, like consumer goods, where Carlyle is smaller, Thomas said.