The Scene

A series of (mostly) successful IPOs have bolstered CEO confidence about entering the public markets, after a yearslong drought.

Private equity firms that own a record 29,000 companies, worth $3.6 trillion, are desperate for exits; the average hold time is now more than six years, up from just over five in 2021, according to Bain &Company. Public investors, still bruised from the IPO and SPAC free-for-all of 2020 and 2021, have signaled an appetite to back profitable companies — a quarter of new entrants this year were in the black when they listed, more than double the level in 2021, PitchBook data shows.

And US regulators are pushing hard to make the public markets more appealing to companies, floating the idea of less-frequent investor report cards. They are worried that an endless supply of private capital will crowd out retail investors, suck investment away from non-AI industries, and lead to a hollowing-out of one of America’s biggest financial and cultural exports: its stock markets.

There are signs it’s working. IPO volumes through Sept. 30, by money raised, is up 70% from the first nine months of 2024, according to Dealogic. Blackstone took its first portfolio company public in four years last month, and is said to be readying another big one in Ancestry.com, which it bought in 2020. Goldman Sachs last month had its busiest IPO week since July 2021, when pandemic boredom fueled a listings binge, not all of it healthy.

“There’s a huge appetite from [public] investors to buy into IPOs,” said Peter McKay, CEO of Snyk, a Boston-based cybersecurity firm that has been eyeing a listing since 2022 and is now moving ahead. The company, which has raised more than $1 billion from investors including Qatar Investment Authority and Tiger, has fielded interest from strategic acquirers but continues to plan for an IPO in the next few months, McKay said in an interview.

Investors “want to see the window open,” he added. “I think that they’re trying to convince companies like mine to go public quick.”

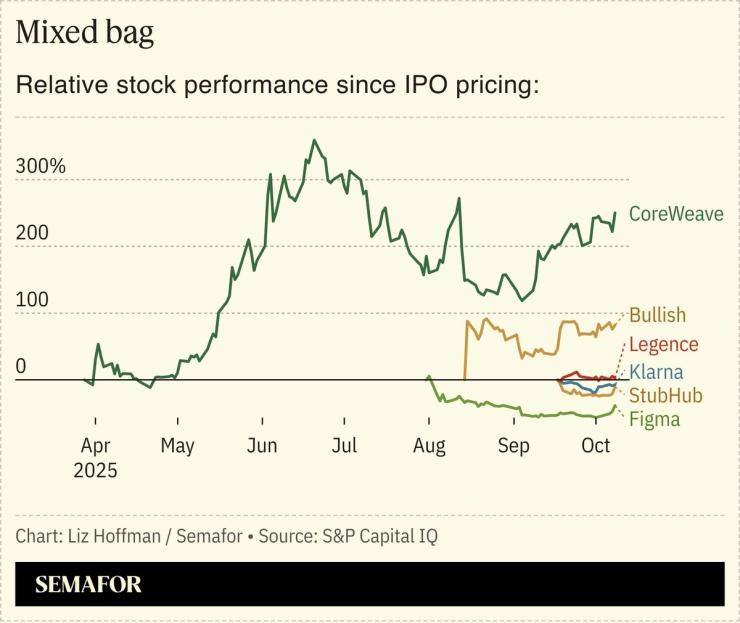

CoreWeave, Figma, fintech Wealthfront, Navan, Netskope, and StubHub are among the firms that have debuted or filed plans to go public. Post-listing performance has been spotty. The Renaissance IPO index is slightly outperforming the broader S&P 500, but that’s thanks in part to huge gains for CoreWeave and Figma papering over weaker goings elsewhere.

Proofpoint, which was acquired by Thoma Bravo in 2021 and uses AI and machine learning to detect online threats, has been preparing for a float that could value the company at around $20 billion, according to people familiar with the matter. Thoma Bravo declined to comment.

“The IPO window looks to be reopening,” Proofpoint CEO Sumit Dhawan told Semafor. “We’ve assessed the market and believe the timing might be near, potentially next year.”

It isn’t just technology companies. Blackstone acquired corporate events firm Encore in 2018 and saw it through a pandemic-induced downturn. Encore’s revenue now exceeds 2019 levels and the company is weighing an IPO, according to people close to the company. Bloomberg earlier reported Encore’s interest.

Know More

The old model for startups (raise a few rounds of venture money, then go public) or buyouts (clean up the business, then relist within a few years) has been upended by the rise of private money as an alternative to being public. Private investment firms raised some $13 trillion between 2014 and 2023, according to PitchBook, whose figures don’t account for sovereign wealth funds, insurers, and other pots of money chasing alternative investments.

“Companies, if they don’t want to go public, they do not have to go public,” London Stock Exchange Group CEO David Schwimmer told Semafor in a recent interview. That’s a challenge for LSEG, which has made a push into private markets as the number of new listings, in London and beyond, dwindled.

“But there are still benefits to being public — liquidity, being able to use your equity as an M&A currency, being able to provide liquid incentive structure to employees,” he said. He added that the decades of low interest rates that aided private equity and allowed companies to forego IPOs are over. “Capital is not free any longer,” he said, and “we’re seeing … a private equity industry that got overextended. That may also lead to a bit of a resurgence in the attractiveness of the markets.”