The Scene

In February 2020, a network of radiologists’ offices owned by a private-equity firm, borrowed $1.3 billion from a group of lenders.

Since then, the company’s credit rating has been slashed twice, deep into junk territory. A federal crackdown on surprise medical bills resulted in its doctors being pushed out of network by some insurers. S&P expects its debt load to exceed 10 times its profits this year.

So what’s that loan worth today? Depends who you ask. Credit funds are valuing — marking, in Wall Street parlance — their slice of Radiology Partners’ loan between 75 and 84 cents on the dollar. All have lowered their marks over the past year, but at different rates.

The portfolios of credit funds, nonbank lenders that are increasingly providing America’s corporate debt, show a veritable dartboard of valuations for the same loans. In a world where loans are expected to trade at face value, and where even a few pennies below suggests deep concerns about payback, these gaps can be significant.

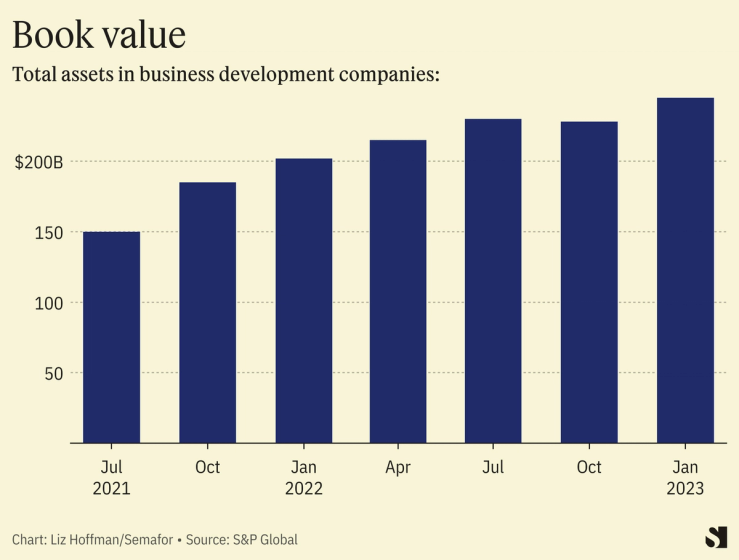

Unlike banks, these companies, called BDCs, have to post their holdings publicly each quarter. And they have grown from $150 billion to almost $250 billion in the past two years alone, according to S&P Global.

BDCs typically hire outside firms like Houlihan Lokey to estimate valuation ranges for each loan, but have considerable wiggle room to pick their own numbers, coloring their marks with their own views about economic growth, the quality of company management — and, some investors quietly grumble, managers’ own desire to avoid acknowledging a deal has gone bad.

With higher rates and lower growth now squeezing borrowers and defaults expected to rise, valuation sleights-of-hand are likely to be revealed.

In this article:

Liz’s view

For all of finance’s spreadsheets and models, a lot remains art, not science. There are legitimate reasons the same loan might be marked differently on different books, such as a team that’s done a deeper dive on a borrower’s customers or prospects.

But they own a lot of the same kinds of loans, mostly supporting private-equity buyouts and portfolio companies. These holdings are considered diversified — what are the odds that midsized manufacturers go bankrupt en masse? Not high, but then again, the idea that home values would plummet everywhere at the same time was considered unthinkable until it happened.

More and more of this lending is happening outside of public scrutiny. I’ve been spending time looking at the quarterly reports of publicly-traded BDCs, and S&P says that 37% of loans are held by more than one BDC, which makes it fairly easy to see who’s outside the fairway on marks. But they are being eclipsed by nontraded vehicles, whose holdings aren’t reported.

When “shadow bank” doomsayers worry about what’s happened to the risk that’s been pushed out of traditional banks and into BDCs, private credit funds and other lightly regulated industries, this is what they’re talking about.

Maybe the underwriting here will prove to be conservative enough — in other words, the loans will eventually be paid back — that the paper marks between now and then won’t matter.

But as BlackRock’s Mark Wiedman told me this week at our inaugural Semafor Business Summit, you didn’t have to be particularly good at lending to make money over the past few decades. Debt was cheap and everything went up, which basically meant anyone with a balance sheet could do it, and investors’ desire to find yield anywhere meant that they were pouring money in.

“We had 40 years where you really looked smart by levering up,” Wiedman said. “That’s over.”

Room for Disagreement

Even if wishful thinking has crept in, it’s hard to imagine this becoming existential. BDCs don’t load up their portfolios with extra debt. Historically they were limited to leverage of 1:1, meaning they could borrow $1 against each $1 of loans they held; that was raised to 2:1 in 2018. In comparison, big banks in 2008 had levered their holdings of risky loans as high as 20 or 30 to 1.

If these loans go bad, the firm will lose money, and it’s possible its lenders might not get made whole. But that’s OK, and unlikely to be existential to the system the way the 2008 mark-to-make-believe was.

In March of 2020, as corporate debt markets were buckling, I broke what I thought was a hot story: That RBC had seized the holdings of a nonbank lender that had gotten over its skis and was dumping its bonds in a fire sale. (This was a real-estate trust, not a BDC, but similar enough for these purposes). I figured it was the front edge of an unraveling of years of shoddy lending. The follow-on stories never materialized.

Notable

- “Just spitballing here, but perhaps, just perhaps, this is a consequences of, you know, not wanting to show that their marks are make believe.” — investor Cliff Asness