The News

Côte d’Ivoire’s 83-year-old President Alassane Ouattara is pitching his bid for a fourth term on his experience, saying he aims to lead the nation to upper middle-income status by 2030, as protests erupted around his decision to run again.

Only experienced leadership can guide the country through “unprecedented security, economic, and monetary challenges,” said Ouattara, an economist and former deputy managing director of the International Monetary Fund, in a video released on social media last week. He also acknowledged breaking his 2020 promise to step aside for a younger generation — a transition derailed by the sudden death of his designated successor. “Sometimes, duty must transcend a promise made in good faith,” he said. “This term will be about generational transition led by the team I will choose.”

Over the weekend opposition supporters protested against Ouattara’s decision to stand again. Former President Laurent Gbagbo’s opposition African People’s Party of Côte d’Ivoire (PPA-CI) said six of its members were arrested in “a wave of repression,” RFI reported.

Know More

Ouattara’s economic platform has so far been scant on details. However, some clues on its direction can be drawn from a document penned by one of the president’s most loyal lieutenants that was published by the IMF less than 24 hours ahead of his rerun announcement.

“The government aims to bring poverty below 20% — down from 50% in 2010 and 37.5% in 2021 — and maintain annual GDP growth around 6.6% through 2030,” Finance and Budget Minister Adama Coulibaly wrote in a letter to IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva.

This ambitious target would, in all likelihood, see Côte d’Ivoire move from its lower middle-income classification to upper middle-income status which is a longstanding goal that Ouattara’s government has said it wants the country to achieve by 2030.

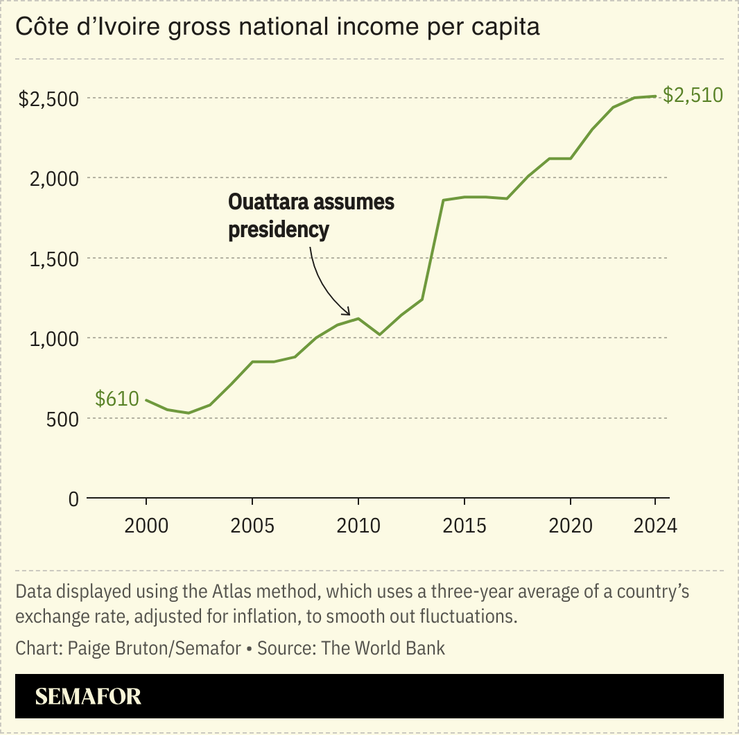

The World Bank determines the classifications according to gross national income (GNI) per capita — the average income earned by a nation’s population in a given year. Côte d’Ivoire, a lower middle-income country, had a GNI per capita of around $2,500 in 2024, whereas $4,495 would push it into the upper middle-income bracket, alongside wealthier African countries such as South Africa, Botswana, and Mauritius.

Step Back

Ouattara’s rerun announcement drew condemnation from the PPA-CI opposition, which called it “a very dark day for the rule of law.” The president’s long silence over whether or not he would seek another five-year term in October’s election has forced the country’s opposition parties into fragile alliances with few and unified messages. Tidjane Thiam, the former CEO of Credit Suisse who was the main opposition frontrunner, was barred from running earlier this year, later forming a front with Gbagbo.

Unseating Ouattara is no easy task, according to analysts. After 14 years in power, his loose coalition commands majorities in parliament, and Outtara’s party secured a symbolic win in Yopougon, the country’s most populated district, during the 2023 municipal elections.

Room for Disagreement

While Côte d’Ivoire is Francophone Africa’s most dynamic economy, the country still lacks fundamental processes, according to Ivorian banker Charles Kié. He cites the need for more legal and fiscal predictability, an independent judiciary, safeguards against executive overreach, and transparent public-sector performance.

“Côte d’Ivoire’s institutional framework remains its most underused lever of transformation,” Kié told Semafor. “Strong, independent institutions — not just growth — are what reassure investors, protect legal certainty, and reduce the sense of crisis that returns with every election cycle.”

On the macroeconomic side, Stanislas Zézé, CEO of Abidjan-based Bloomfield Intelligence, warned that Côte d’Ivoire’s trade surplus is shrinking as imports outpace exports — an early sign of structural imbalance. “Industrialization remains weak,” he told Semafor, “constrained by outdated equipment, a large informal sector, and a mismatch between available skills and industrial needs.”

Concerns also persist within Côte d’Ivoire’s business elite. “The Ivorian business community is raising tough questions,” said Georges Yao Yao, co-founder of the advisory firm Y3 Audit & Conseils. “Among them: the sustainability of public debt — where government reassurances haven’t fully dispelled doubt — and customs policy, particularly access to key export markets like the US.”

Joël’s view

Ouattara is betting that continuity — not clarity — is enough to secure a fourth term. With the economy still growing and the opposition divided, he may be right in the short term. But the long-term question remains unanswered: Who comes next, and on what institutional foundations?

The “generational change” he promised remains undefined. Behind the scenes, names like Patrick Achi and Robert Beugré Mambé, the former and current prime ministers, circulate. Other powerful figures are also maneuvering for position, among them: National Assembly leader Adama Bictogo, who fought fire with fire to win the Yopougon municipal election, as well as Cissé Ibrahim Bacongo, governor of Abidjan and executive secretary of the governing coalition.

Even the identity of the next vice-president is unclear. In Côte d’Ivoire, the elected president chooses the VP, subject to parliamentary approval. Ouattara’s current number two, Tiémoko Meyliet Koné — a respected former central bank governor — is seen as loyal and dutiful, but not a future president.

After months of delay, Ouattara has laid out the case for continuity. But not, yet, for succession.

Notable

- Ouattara’s bid for a fourth term risks a return to an era of “old guard dictator rule” in a region where democracy is increasingly being challenged, Ibrahim Anoba, an analyst at nonprofit foundation Atlas Network think tank, told The Associated Press.