The News

A growing power struggle between Senegal’s president and prime minister threatens the government’s efforts to address the country’s worst economic crisis in decades.

A credit downgrade by ratings agency S&P this month was already making it difficult for Dakar to tap international capital markets after support from the International Monetary Fund was frozen last year. Francophone West Africa’s second-largest economy also faces soaring borrowing costs months after an audit suggested the public purse was in a much worse state than previously thought.

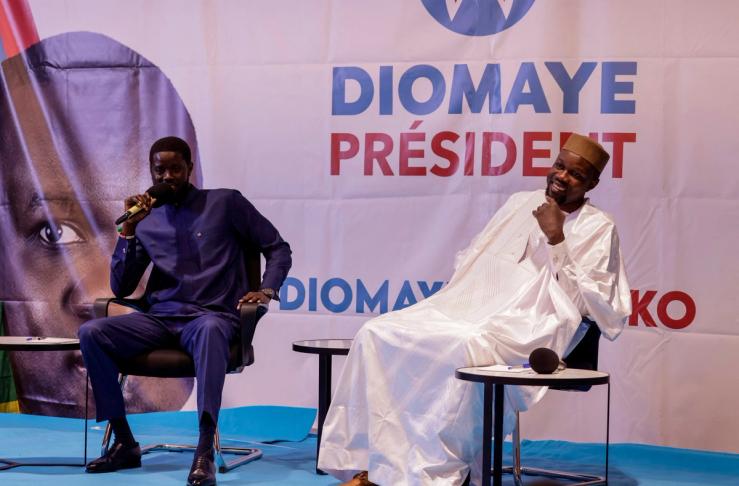

Now strains have appeared in relations between the architects of the current government just as the 15-month-old administration faces its biggest challenge yet. In a speech on July 10, Prime Minister Ousmane Sonko accused President Bassirou Diomaye Faye, his former political protégé, of failing to defend him from “unjust attacks” and “insidious obstacles.”

In the speech to his party, the African Patriots of Senegal for Work, Ethics and Fraternity (PASTEF), Sonko said: “Senegal doesn’t face a crisis — it has an authority problem.” And, referring specifically to Faye, he added: “Either he fixes it, or he lets me fix it.” The premier also lambasted the civil service and judiciary in the address.

Know More

Sonko, 52, and Faye, 45, share a long working history that encompasses great camaraderie: They met in 2007 as public finance inspectors and co‑founded their party, PASTEF, in 2014. Sonko became the party’s figurehead, running for president in 2019 and placing third, while Faye occupied senior positions in the background. Sonko was the most high profile opposition politician in the latter stages of Macky Sall’s 12-year presidency.

Separate cases — that some say were politically-charged — saw both Sonko and Faye jailed in the run up to the March 2024 election. They were freed only days ahead of the vote in March last year. A defamation conviction crushed Sonko’s hopes of running in the contest. Faye, selected by PASTEF to contest the election, won and appointed Sonko as his prime minister.

The premier’s critical comments two weeks ago came days after a Supreme Court ruling that upheld his defamation conviction, threatening a potential run for the presidency in 2029. In a country where the president is believed to have influence over the judiciary, many thought Faye could have stopped the judicial proceedings, Senegalese journalist Ousmane Ndiaye told Semafor.

Sonko’s remarks also overshadowed Faye’s recent trip to the US, noted political analyst Abdou Fleur, where the president had pitched Senegal’s mineral wealth and “stability” as an investment destination in a bid to appeal to US President Donald Trump’s interests on the continent.

Step Back

Both men have exchanged public gestures of conciliation since Sonko’s explosive comments. On July 14, Faye called Sonko “his brother” in parliament, saying they were united in tackling the difficulties the Senegalese — “as well as this government” — were facing.

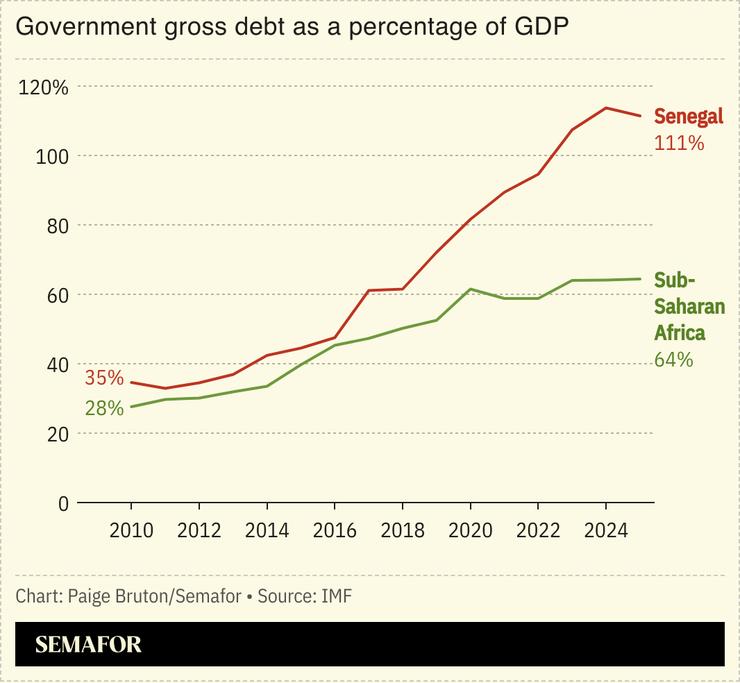

Yet this rift still coincides with a deepening fiscal crisis. Seeking to discredit their predecessors, the government ordered audits soon after taking office in April 2024 that uncovered $13 billion in hidden debt accumulated between 2019 and 2023, prompting Standard & Poor’s to downgrade Senegal twice in six months.

Former President Sall dismissed the audits as technically unsound, but the announcement of nearly a quarter of GDP in unreported debt embarrassed the IMF and World Bank. Financial operators have already priced in the new numbers, leaving little room for Senegal to maneuver.

The audits — though politically useful — backfired economically. Donors and investors took them at face value, freezing support and driving bond yields to record highs. External grants fell more than 70% year-on-year by early 2025. Since disbursing $200 million in December 2023, the IMF has withheld further payments, demanding reforms to prevent “misreporting.”

The World Bank’s $115 million package to Senegal in late June reflected similar caution: just $10 million was earmarked for technical assistance, the rest was tied to measurable reforms. During its March visit to Dakar, the IMF met directly with Faye — bypassing Sonko, in a rare signal of the crisis’ gravity.

Meanwhile, Senegal’s $1.1 billion 2017 eurobond — a proxy for its ability to borrow — has seen yields climb from 8.6% to 12.8% over the past year. In July, both Senegal and Côte d’Ivoire sought to issue five-year regional bonds; Abidjan’s was fully subscribed, but Senegal withdrew its tranche, an unmistakable sign that the issuer judged the rates asked too high.

Joël’s view

“We have a government discovering itself powerless and unprepared,” journalist El Hadj Gassama told Semafor. That may be harsh: Sonko’s speech to lawmakers in December laid out an ambitious policy plan — including a zero-based budget in 2026, a crackdown on tax exemptions, tighter payroll and subsidy control, and plans to tap domestic and diaspora savings through “patriotic” bonds and Islam-compatible bonds.

Whether such politically sensitive measures — reversing tax breaks and cutting subsidies — can survive parliament is unclear. Sonko complained in his address about factionalism in the ruling coalition and of his own failed attempts to secure Faye’s overall backing through the National Assembly President Malick Ndiaye.

Deeper differences may be at play. Ndiaye noted how Faye’s conciliatory approach to dealing with challenges in government contrasts with Sonko’s demand to purge loyalists of the former regime.

For now, the sovereignist agenda that carried both Sonko and Faye to power risks being consumed by the very crisis it sought to expose — with Sonko now the face of promises his government may struggle to keep.

Room for Disagreement

Economic analyst Abdoul Wahab Touré said the government deserves more credit for its handling of the economy. “If resources are used wisely, there’s no reason Senegal couldn’t achieve double-digit growth,” he said, cautioning against over-investment in construction at the expense of vocational training and agriculture.

Notable

- Many African governments spend more on debt servicing than health and education, notes Al Jazeera in a short film, asking whether nations across the continent will “ever be able to repay their debt.”