The News

LAGOS — Nigeria’s President Bola Tinubu vowed to usher in an era of renewed hope when he was inaugurated into office a year ago. Twelve months later, the prices of food and fuel have doubled, driving increasingly loud discontent.

Tinubu’s first anniversary, on May 29, comes as the country is set to slip two places to fourth on the ranking of Africa’s largest economies, according to the IMF.

The president had promised to deliver higher economic growth, a million new jobs and security reforms. On his first day, he removed a decades-long subsidy on petrol that had made it relatively affordable for consumers. He charged the central bank’s new leadership to pursue a market-driven exchange rate. The bank has hiked the benchmark lending rate by 7.5 percentage points since February to tame inflation.

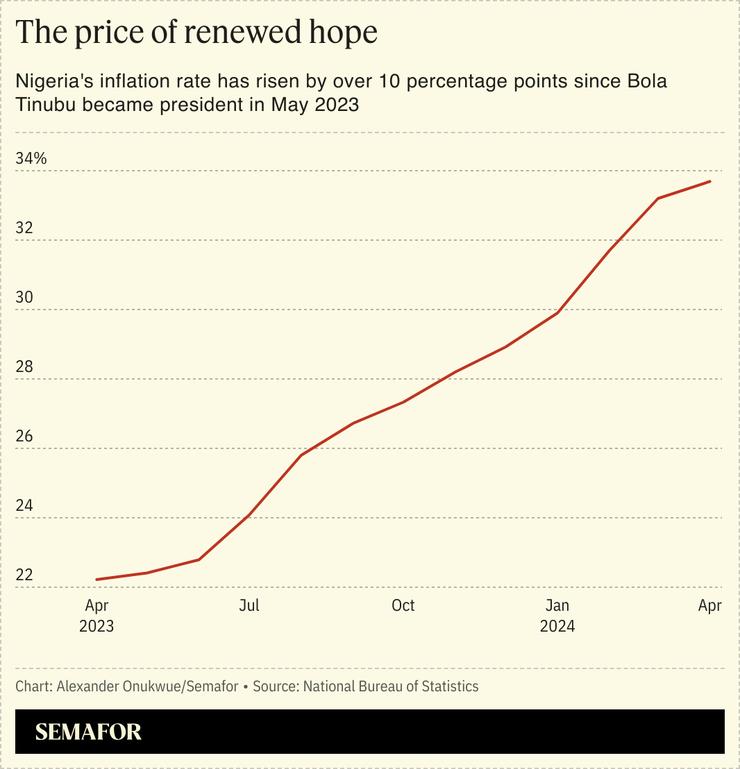

But Nigeria’s inflation has climbed to a three-decade high instead — up to 33% from 22% over the past year.

“It has felt like a very different country because things are so hard,” Olusegun Akinsanya, 53, a father of three who works at a furniture company in Lagos, told Semafor Africa. His employer moved from paying fixed salaries to a per contract basis in response to the state of the economy, he said. “I don’t have any hope in the president and he doesn’t have any plan for us.”

The largest union for Nigerian government workers has demanded a tripling of the $20 national minimum monthly salary to match the fast rising cost of living. The government last week offered an increase that falls short of doubling the minimum, which the union rejected.

Know More

Tinubu rode to power promising better economic management than his predecessor Muhammadu Buhari, a former military ruler who favored import restrictions and central bank control over the naira currency’s value. Nigeria endured two recessions during Buhari’s eight-year tenure.

As the petrol subsidy removal sent prices soaring last June, Tinubu said Nigerians must bear the pain to “save our country from going under and take our resources away from the stranglehold of a few unpatriotic elements.” The subsidy — which at nearly $10 billion in 2022 cost over four times the budgets for education and health respectively — has been reintroduced, according to the IMF and fuel traders even though the government has not formally announced it. Meanwhile the average price of petrol is double what it was in May 2023, according to the government’s statistics agency.

Nigeria’s naira has lost about 60% of its value following two devaluations in June and January. The IMF projects the size of the economy to be $253 billion this year, a steep drop from over $470 billion in 2022, according to the World Bank and further away from Tinubu’s stated ambition to turn Nigeria into a trillion-dollar economy by 2030.

Internal security remains volatile despite Tinubu’s pledge to prioritize reforms. Deaths due to abductions or gangs taking over territory across the country have risen by nearly a quarter, to around 1,900 people, since his first day, according to ACLED, a conflict research non-profit in Wisconsin.

Alexander’s view

Many Nigerians feel worse off than before President Tinubu was sworn in a year ago, despite his attempts to signal stability and clarity. “My business is stagnant because everything is expensive in the market and so customers don’t buy,” says Motunrayo Adaramaja, a road-side trader in the Surulere area of Lagos. She has limited her stock to items like small noodle packs that she can buy and sell off without owing suppliers.

Tinubu got off to a quick start in choosing his cabinet and signaling an economic plan, compared to his predecessor. “He and his team have shown some hustle and this has produced some modest but discernible improvements to the country’s economic and security situation,” said Matthew Page, an associate fellow at the London-based Chatham House think tank.

Oil production, on which Nigeria relies to fund a $34 billion budget for this year, rose to 1.57 million barrels per day between January and March as the authorities clamped down on oil theft and other challenges. It’s the highest level since September 2021. Looking ahead, Dangote Refinery — a 650,000 barrels-per-day processing facility in Lagos owned by Africa’s richest man Aliko Dangote — is expected to ease Nigeria’s reliance on imported oil products after it began production this year.

But Page believes Tinubu is merely “mismanaging Nigeria less badly” than Buhari did, with the situation still “objectively bad.” Despite international trips to invite foreign investors, the president has maintained structures of “grand corruption in plain sight” that undermine Nigeria’s long term socioeconomic trajectory, Page told me.

Some of Tinubu’s choices — like the continued subsidy of pilgrimages, including 90 billion naira ($60 million) for this year’s Islamic pilgrimage to Mecca — already betray an eye towards re-election in 2027, says Ayisha Osori, a Nigerian lawyer and director at the Open Society Foundations civil society network. “We know as a country that this is a luxury we cannot afford but Tinubu has to appease the ‘elite’ who will benefit most from these plans,” Osori told me.

Room for Disagreement

Nigeria is on a road to recovery, the government insists. “Our economy has turned the corner. By the coming months, the economy will roar back to glory,” the vice president Kashim Shettima, speaking on Tinubu’s behalf, told state governors and legislators on April 12.

The View From Washington DC

The Tinubu administration has struggled to effectively communicate its direction to Nigerians over the past year, said Amaka Anku, who heads the Africa practice at the Eurasia Group consultancy. “They have not done a good job on creating a rallying cry that people can buy into,” she said. The central bank’s push to stabilize the foreign exchange market has not been matched on the fiscal side with similarly clear policies on agriculture, trade and security, she said.