The Scene

Fears of an economic downturn and consumer belt-tightening will test Wall Street’s favorite new business model: subscriptions for everything.

Since the 2008 recession, the world of commerce has been consumed by subscriptions. Dry cleaning, razor blades, car washes, food delivery, sneakers, dog toys, bottles of wine, dental cleanings — things we used to buy as needed — are now sold as subscriptions (“memberships” for pricier items) that promise a set-it-and-forget-it world of abundance and convenience. They have hit on a fact that gyms have long known: people don’t use memberships as often as they think they will, and they don’t usually cancel.

Fueling this trend is a Wall Street money machine ensorceled by these steady payments. Because those cash streams can be forecast more reliably than episodic sales, they can be borrowed against. A marketplace for loans underpinned by what investors call “recurring revenue” has grown quickly.

But now two forces are testing that model. First, consumers are terrified about the economy and cutting back on some spending.

Second, regulators are cracking down on the mazes of corporate trickery and psychological nudges that make it hard for customers to cancel. The Biden administration sued Amazon and Match for alleged use of these “dark patterns,” and the Federal Trade Commission’s lawsuit last month against Uber over its subscription product, Uber One, shows that Trump appointees are just as focused. A 2024 study of 642 websites and subscription services by international regulators, including the FTC, found that 76% of them used at least one “dark pattern.” (The companies have denied the allegations. Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi told Semafor the FTC lawsuit was a “head-scratcher” in April.)

Just as consumers are taking a closer look at their expenses, the government is serious about making it easier for them to cancel them. A slew of financial-management apps will even do the cancelling, giving rise to a new business model: Rocket Money takes a cut of the money it saves people.

As subscription fatigue has set in, “people are increasingly aware of what they’re getting value from and what they’re willing to pay for,” said Tom Hale, CEO of Oura, which makes the wellness tracker ubiquitous among the moneyed tech set. He believes Oura is protected by what he calls the “Peloton effect.” Without a subscription to its sleep-tracking software, Oura rings are just hunks of metal — nice-looking ones, Hale is quick to note, but not that useful.

“It’s not just that people have health goals — it’s that and ‘I spent $300 on this thing,’” he said. “That’s so different from other subscriptions, where the value isn’t as obvious and all of a sudden people are going to say, ‘When’s the last time I used this?’”

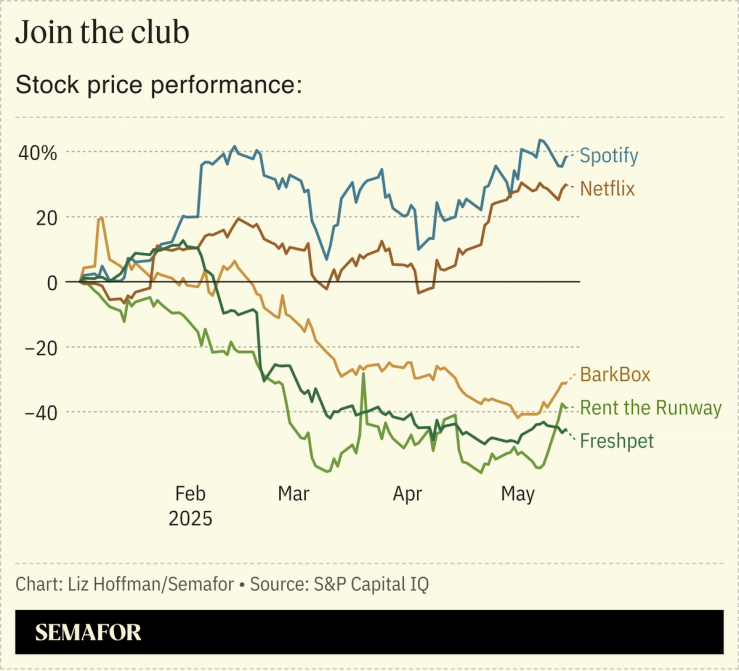

It’s early going yet — and Trump’s climbdown on tariffs may brighten the economic mood — but already the market is distinguishing between recession-proof subscription models and those likely to be canceled.

Netflix CEO Ted Sarandos stopped short of calling the company “recession-proof” in a recent interview, but said it was “resistant.”

“In tough economic times, it’s very important to focus on the things that you can control, and for us, what we can control is that Netflix is a great value,” he said at Semafor’s World Economy Summit last month. “It’s like 30 cents an hour of entertainment, and it’s high quality entertainment.”

In this article:

Know More

The subscription model started in the early 2000s in software, where it was a no-brainer for companies to replace one-time purchases with pay-as-you-go access. It jumped to consumers with streaming, and was cemented there during the pandemic, when delivery became the new normal and shopping habits were tweaked by hoarding and self-care.

Turbocharging that business model was a gusher of Wall Street money. Huge piles of cash have been raised by credit funds that are seeking predictable, recurring cash flow. Half a dozen private credit shops have lent to a firm called Mammoth Holdings, a car-wash chain owned by a private equity firm that offers unlimited monthly passes starting at $17.

So what happens now?

One metric to watch, according to one popular trade newsletter, is the discount a company offers for an annual subscription over a monthly one. Bigger discounts for longer plans mean companies are worried about cancellations — think apps for weight loss, test-prep, and dating. Dan Layfield, a consultant for subscription businesses, notes that utilities don’t tend to offer annual plans. (Hale points out that Oura costs $6 a month, or $72 a year, and offers annual subscriptions for just a touch less, at $69.99.)

When Hale worked at Survey Monkey in the mid-2010s, “we talked about the ‘sleeping bears’” — customers that were paying for the product and not using it. “Don’t poke the sleeping bears,” he said.

Liz’s view

Recessions wash out bad business models, and that’s what will happen here. It makes sense to subscribe to contact lenses. Less so to subscribe to car washes. Some lenders are going to realize that not all “recurring revenue” is the same. Some companies will fail, and some lenders will take losses. Assumptions made during flush times often don’t hold, and consumer belt-tightening might show subscription mania to be one of them.

The View From Universal Music

“Good value for money,” is how Universal Music CEO Lucian Grainge describes his business.

“When there’s been inflationary pressure and household budgets tighten, music subscriptions and music purchase has always been resilient,” Grainge said on his quarterly earnings call two weeks ago, when the company reported a 9.3% jump in subscription revenue.

Notable

- Private equity wants to wash your car, as many times a month as you want, for one flat fee. — WSJ