The News

African policymakers will push for global finance reforms and new financing models to address the continent’s spiraling debt crisis during three days of crunch talks convened by the continent’s regional body.

Africa will pay nearly $89 billion to service external debt this year, with the majority of its obligations owed to private creditors, according to the ONE Campaign, a Washington, DC-based advocacy group. The debt service bill amounts to about 25% of Africa’s combined GDP in 2023, up from about 15% a decade ago.

Meeting in Togo from Monday for the three-day African Union event will give policymakers an opportunity to compare notes on recent debt management experiences, and there are “some signs that the region has taken lessons” from the debt defaults of Ghana and Zambia, said David Omojomolo, an emerging markets economist at London-based firm Capital Economics.

Combined with the reduced urge to issue foreign currency debt, African countries are “increasingly turning to concessional or local currency sources of financing,” Omojomolo said. Debt-distressed Kenya’s intention to raise $3.86 billion from a diaspora bond — tapping into the economic power of nationals in richer countries — points to new thinking, he said.

In this article:

Know More

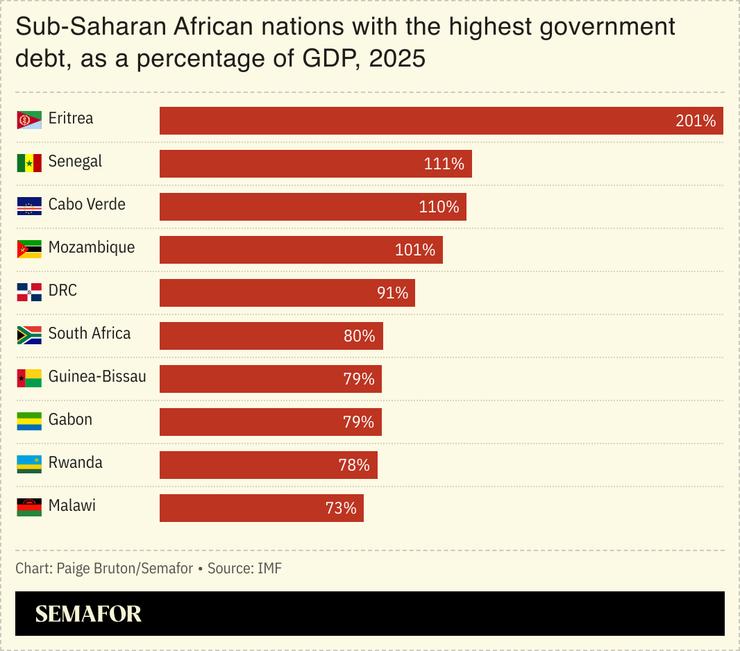

The continent’s debt picture in the last half decade has been dominated by sovereign defaults by Ghana and Zambia, as well as poor fiscal health in leading economies such as Ethiopia and Angola. The International Monetary Fund and the G20’s Common Framework have played key roles in providing some relief with negotiated repayments and staggered stimulus packages. Still, about 20 of Africa’s 54 countries are in — or at least at risk of — debt distress, the ONE Campaign said.

Policymakers and key decision-makers from African finance ministries and central banks are expected to propose “Africa-led solutions” to the debt crisis in Lome. The meeting, convened by an economic development and trade department of the AU Commission, is a less powerful organ than the AU’s Assembly of Heads of State and Government. It is unclear if presidents of African nations will attend the convening.

The talks come amid an upheaval of the global economic climate due to the US government’s drastic policy shifts, especially the imposition of trade tariffs. Washington’s pullback from development finance and humanitarian aid in Africa has also become a key part of the debt conversation.

Aid cuts by the US and European nations “might lead to pressure on governments to borrow more” as they try to replace lost aid funding which supported their health and education budgets, said Charlie Robertson, head of macro strategy at asset management firm FIM Partners. That funding won’t be cheap, Robertson said, but African countries have learned that cheaper, more competitive currencies can reduce real interest rates and therefore lower risk of debt defaults.

Trump’s protectionism does not bode well for Africa but “we are not so convinced that there’s a link between Trump’s Africa specific policies and debt servicing,” Omojomolo, of Capital Economics, said. On the contrary, a tariff war and a weak dollar could mean that countries like Kenya and Mozambique with high forex debt “are probably seeing [their] debt servicing burden even ease,” he said.

The View From Abuja

Nigeria paid off a $3.4 billion loan borrowed from the IMF in 2020, the lender said last week. At the end of 2024, Nigeria’s external debt stock stood at nearly $46 billion, according to the Debt Management Office in Abuja, most of it owed to multilateral lenders including the IMF, the World Bank, and the African Development Bank.

Notable

- About 900 million people in Africa live in countries that spend more on interest payments than on health care or education, The New York Times noted in an August story on the “catastrophic” impacts of Africa’s debt crisis.