Semafor Business’ signature interview series, On The Record, brings you conversations with the people running, shaping, and changing our economy. Read our earlier conversations with Robinhood CEO Vlad Tenev on life after the meme-stock craze, Mattel CEO Ynon Kreiz on Hollywood’s golden age of IP, Washington Post CEO Will Lewis on the media doom cycle, and Delta CEO Ed Bastian on the 2020 airlines bailout.

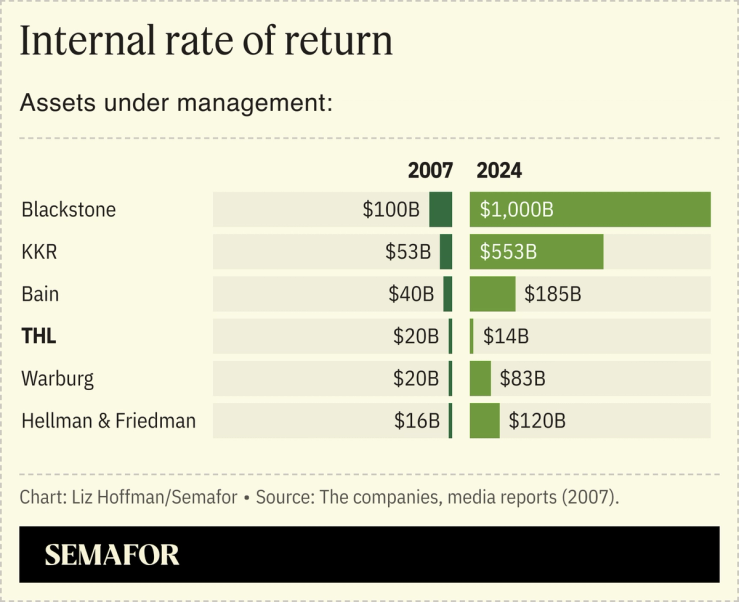

Private equity is undergoing the most dramatic reshaping in its 50-year history. Firms are bulking up and branching out, adding credit, insurance, and infrastructure arms. Blackstone became the first to manage $1 trillion but won’t be the last, and buyout shops are increasingly oriented around their public shareholders, not fund investors.

THL is doing none of these things. It sold its lending arm in 2020. It doesn’t have a Bermudan reinsurer or a real-estate arm or IPO plans. While most of its competitors are neither private nor equity-focused, THL is defiantly both.

Founded in 1974 by Thomas H. Lee, one of the earliest buyout titans, the firm helped create modern private equity and cemented Boston as one of its early hubs. In the 2000s, it joined the industry’s rush toward megadeals and became a household name with takeovers of Warner Music, Aramark, Clear Channel, and Dunkin’ Donuts. (Lee later left the firm in an acrimonious split, and died last year of an apparent suicide.)

The firm he founded is smaller today than it was a decade ago, managing $14.4 billion in assets, a trendline that should be fatal for an asset manager. Instead of splashy buyouts, it makes its money in smaller companies in healthcare, tech, and financial services.

But unlike many of its competitors, it is making money — at least in the sense of putting actual cash in investors’ pockets. While rivals are stuck holding companies they can’t sell or take public, THL’s latest fund, raised in 2019, has already returned 138% of its money, versus 10% for the average North American buyout fund raised that year, according to Preqin. It has avoided brand-name deals that command nosebleed prices, and instead put manageable amounts into businesses that throw off cash.

I spent an hour with co-CEO Scott Sperling, 66, in his spare Boston office, where pictures of his grandkids rotate on a TV screensaver and his computer is open to a spreadsheet detailing a carry trade that I can’t quite make out. I pushed him on whether THL is being left behind by an industry it helped create

Liz Hoffman: Are you consciously contrarian?

Scott Sperling: We think we know what we’re really good at and where we can be the best, and we’ll focus there. It happens to be an area where the economics are very attractive. We’re mostly domestic. We’re not doing credit. We’re not doing real estate. We had a credit business that we grew to about $18 billion of assets and it was a really nice business. But the scale needed [to compete] kept getting bigger and bigger in that arena. First it was $15 billion and you’re a player, then it was $25 billion and then $50 billion. First Eagle made us an offer we couldn’t refuse.

In thinking about whether to [rebuild a credit business] after our noncompete came up, we decided that the amount of diversion from a senior management perspective wasn’t worth it. So we’re going to double down on what we’re doing.

You’re smaller than you were before 2008, in an industry that tends to pride itself on growing assets.

Big funds take a long time to invest. That’s not good from gross to net, and it’s not good internally because as people grow, they expect that they’re going to get more economics, and it’s easiest to reset economics as you change funds. So we reset.

Asset accumulation is not that important to us. We get paid on the profits we make. So we’d rather focus on that as a key metric than total AUM, where, for the public guys, they know that the [share price] multiple they get on management fees is dramatically higher than the multiple they get on carry.

They also made up an earnings metric and convinced everyone it was real.

Yes. I still don’t even fully understand it. But, you know, whatever. We’re much simpler.

So you’re not interested in going public?

Our philosophy is that the active partners should control and benefit from the majority of the economics that flow to the GP. Once you’re public, that’s no longer true. We also think the alignment of interests with LPs loosens dramatically. You have another fiduciary obligation — to public shareholders — and the metrics that they use are different. And so you get rewarded for asset accumulation. I’m not saying that’s morally reprehensible. It can be a phenomenal business model and the big public players have done a really nice job, but they’re different animals right now than we are.

The other reason people go public is that they don’t do a good job of transitioning ownership of the firm to the next generation. How do you think about that?

We have the benefit of having had the major transition 20-some years ago from a founder, who, for the early part of our firm, was also the largest economic recipient of its benefits. And we’ve now had a few handoffs going back to 1999, when we cut a deal with Tom [Lee] to buy him out of the firm. So we’ve gone through that. It’s not something that we feel we need an external enabler to do. [Sperling’s co-CEO, Todd Abbrecht, was elevated in 2020.]

The other option is somewhere in the middle — selling a stake in the firm. Is that interesting to you?

As you can imagine, we get approached a lot. We’ve made the decision that, particularly given how much our firm has grown, we want to have all those economics for active partners. Back in 1999, Putnam bought a passive piece of our firm, which helped enable the handoff [from Lee]. That had about a 10-year life to it and it was great. They made a lot of money. It was good for us. But if we go back to 2005, we were 34 professionals and 11 or 12 partners, and today we’re almost 150 professionals and 40-some partners. So having all the economics has been beneficial.

There’s a sense that LPs want to streamline and do more business with fewer managers and that preference will force niche managers, who might be really good at one thing, to consolidate into superstores. Do you buy that?

I don’t know. I’ve been doing this for 40 years, and every year there are more and more firms. Will a whole bunch of them disappear or get acquired? It’s not clear what the advantage to that is to LPs. ‘Gee, I’d rather give you all my money, because then I don’t have to … do what? I don’t have to talk to anyone else?’ I don’t think they’re yet at the point where they’re moving all their chips over to five players who may or may not perform as well in any single given area.

Well, they can probably get a discount on fees. But you think they make that money back from you in better performance?

Yes.

You own a bunch of software firms, but you also own a business that sends home care aides out to seniors and kids with autism. Those are really different businesses.

We will only invest in things that have strong growth tailwinds that we think are sustainable, where we can be on the right side of technology change — healthcare, financial technology, business solutions. We just closed on our second automation fund.

We used to invest in consumer [companies]. We had great heritage in it, but it lost those strong growth drivers that we were looking for.

Everyone in your business is trying to figure out how to sell to retail investors.

Alternative assets have performed well over very long periods and even most short term periods. That outperformance has long attracted the ultra-high net worth, but now it’s moving down to be something that advisors are looking at for their moderately high net worth clients.

Is there real demand though? Because the concern is that these products are driven more by firms wanting more assets.

I think it’s probably both, but yes, there is real demand.

In the 1980s I got recruited to start an alternative asset area for Harvard, working for Walter Cabot. By the time I left, it was like 22% or 23% of the endowment, and the reason was that it just outperformed public assets. But for the first two or three years, every few months, I’d go into the Harvard Corporation and explain why this was still a good thing to do.

I think we’re doing the same thing now with retail. These are smart people, and they have smart advisors and they’re going to look at the data. And the data are highly supportive of having this be part of [investment portfolios].

Blackstone got into some trouble with some products that were not as liquid as they thought and that’s always going to be an issue with retail, which might say they’re fine with being stuck long-term in things but reliably change their minds when they get spooked.

Yeah, the industry will probably look at lots of different structures to see what sells. But I don’t think that bad experience will cause them not to pursue retail investors.

The lending that’s moved out of the banks into private credit — is that shift permanent, or will a lot of it migrate back?

The big banks got into trouble because they underwrote things that were not worth what they thought and they got stuck holding them. Once that’s cleared, and a little bit of time passed, they’ve come back with a product that is competitive and often cheaper.

That was a really nice way of not saying ‘Twitter.’

There were a number of buyouts in there that got sold at 80 to 90 cents on the dollar. But banks are much more aggressive today than they were 18 months ago. They have decided they want to compete more aggressively against private credit, or join the club. All of that just gives us more choice.

High-yield spreads are back where they were two years ago. Credit is getting pretty loose again. Do you think investors are getting lazy, or ignoring risks?

I’m a bad person to ask because I’ve been fearful for quite a long time and I’ve been wrong so far.

I worry about how far the consumer has stretched and the amount of refinancing the federal government has to do. And I think the macro issues that [the market] has tended to just absorb and just keep on are riskier than most investors feel they are. I hope I’m wrong, but we need to understand that there are lag effects. When I hear people say, ‘Oh, but the consumer is still going strong’ — have you seen their credit card balances recently? The impact of higher mortgage rates was muted by the fact that fewer people were moving or refinancing. But you’re starting to see that turn.

All of this is to say that I think there needs to be some risk premium built into investing. Long-term rates don’t have to be crazy high — like my first mortgage was 17% — but they’re not going to be 2%, either.

M&A has been slow, the IPO market is shut, and there are trillions of dollars of companies that you and your competitors own and can’t sell. You can do continuation funds, you can take out a NAV loan —

We don’t do those. I don’t like money with a rubber band on it, number one. And number two, I don’t think LPs ever counted on incremental debt. So I’m not a fan.

OK. But lots of people are, as a way to return money.

Our distributions for fund 7 and 8 are well above 100%. So we don’t have a big backlog, which is fortunate, given where the market is. But anything you bought in 2021 or 2022 will take longer to get to the [return] multiple that you’re looking for. Especially for people who were very aggressive on valuations, when everything looked like it was going to be great and multiples were forever going up.

But we sold a healthcare IT company last year for 23.6 times EBITDA. We had dramatically increased the growth and earned that multiple expansion, and we got it. So even in this period, if you have a good asset, you’re going to be able to sell it.

It’s an election year, which generally isn’t great for markets. Anything you’re watching for?

How much worse can it get? Actually, probably a lot worse.