The News

The number of Africans entering Britain as care workers nearly trebled over the last year after visa rules were changed to tackle staff shortages exposed by the COVID-19 pandemic and Brexit. It highlights the West’s growing reliance on migrants from the world’s youngest continent to care for its aging populations.

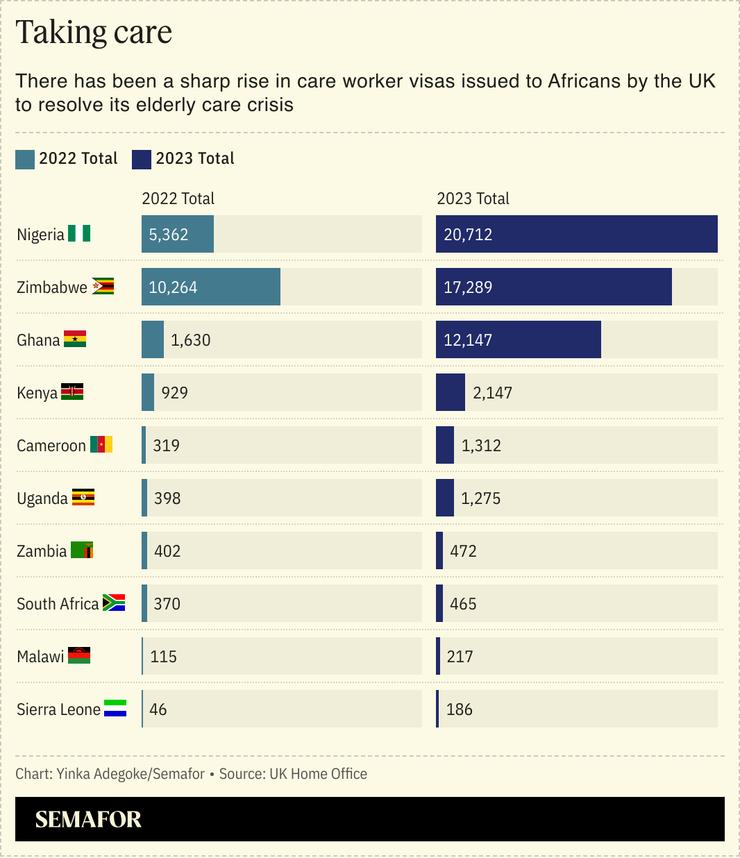

Africans now make up the majority of foreigners given the right to work in Britain’s care system. Some 57,000 Africans entered the country on a Health and Care visa in 2023 — up from just over 20,000 in 2022 and more than half of the approximately 106,000 granted the right to travel to Britain for that work, Semafor Africa’s analysis of newly released Home Office data shows.

Britain’s government in December 2021 added care staff to a list of occupations for which visas would be granted to address a shortage of workers which rose sharply during the pandemic.

The UK’s health ministry said it was acting on recommendations made by the Migration Advisory Committee (MAC), an independent body that advises the government. The MAC, in its 2021 annual report, also said restrictions for care workers needed to be eased due to the impact of the United Kingdom leaving the European Union. “The ending of free movement and the absence of a work route for care workers is likely to contribute to the recruitment problems faced by the sector,” the body warned.

Know More

The increase in Africans securing care worker visas was largely driven by applicants from Nigeria and Ghana, countries that in the last two years have both endured economic crises characterized by skyrocketing inflation and high youth unemployment.

Nigerians received nearly 21,000 care worker visas in 2023 — second only to India and roughly four times more people than the previous year. And the number of Ghanaians entering Britain on a care worker visa rose to 12,147, a marked increase from 1,630 a year earlier.

Zimbabwe and Kenya, both countries that have also grappled with a rising cost of living in recent years, were among the other African nations in the top 10 countries from which immigrants were granted care visas last year.

Alexis’s view

The sharp increase in the number of Africans working in Britain’s care sector illustrates a clear demographic trend — the world’s fastest growing continent will increasingly make up the shortfall of workers in Western countries. That makes sense for a continent that is expected to make up a quarter of the world’s population by 2050.

“We’re seeing absolute declines in the number of working age people in rich countries that we haven’t seen since the Black Death [of the 1300s],” Charles Kenny, an economist and senior fellow at the Washington-based Center for Global Development think tank, told me. He said that will create “a massive demand for workers from somewhere, and for Europe the obvious place is Africa.”

The care visa trend highlights the extreme contrast between the youthfulness of African nations and the aging populations of advanced economies in the northern hemisphere. That gulf was crystalized during the pandemic.

Beyond the demographic advantage, the rapid rise of African caregivers into the U.K. highlights two other trends. The first is that the increased cost of living and lack of jobs seen in several African countries is forcing young people to seek opportunities beyond the continent, where the pay is relatively high. The fact that care work doesn’t require a higher level of education or special skills opens up care work to those who aren’t qualified medics, for example. Even qualified nurses are leaving their home countries to take care jobs.

The second trend to bear in mind is that African workers will continue to fill worker shortages in the aging workforces of the West — but, without vast improvements in education systems, it will continue to be in roles that are poorly paid. Advances in technology like AI will reduce the need for foreign workers in skilled jobs, leaving only opportunities for work — like caring for the elderly — that literally requires a human touch.

Room for Disagreement

Britain’s government this month introduced a rule change that means people entering the country on a care worker visa will no longer be able to bring family members. Much like similar restrictions placed on foreign students, it is part of its attempt to cut net migration and it could deter Africans from seeking work as carers.

“Available data suggests that health and care workers are more likely to come with partners or children than people on other work visa routes,” said Madeleine Sumption, director of the Migration Observatory analysis body at the University of Oxford. “Some will no longer want to come if they cannot bring their immediate family.”

The View From Nairobi

Esther Mboko, who runs a recruitment agency in Nairobi, said demand in Kenya for caregiver jobs in the U.K, U.S and Gulf States had been growing due to high unemployment and the rising cost of living.

“Some agencies are now recruiting up to 1,000 caregivers at a time to send to the U.K, and I can assure you there is no shortage of interested applicants,” she said. Mboko said she expected even more Kenyans to work as caregivers in the U.K. in coming years as people continue to live longer in the West while failing to introduce more young people into its workforce. She pointed to research by social care organization Skills for Care indicating that the U.K. may need an extra 480,000 workers in social care by 2035 to keep pace with demand.

Rights campaigners fear employers who sponsor foreign carers have too much power over caregivers who rely on them for their stay in the U.K. and are often poorly paid by the country’s standards. They argue that removing the right to bring family members will heighten these problems because workers will be alone in the U.K. and unable to benefit from the extra income of their spouse. Mboko argued that such concerns, and related fears about the exploitative practices of some Kenyan recruitment agencies, were unlikely to deter people. “Most applicants know there are risks of course, but they are willing to take them because of their current situation,” she said.

— Reporting by Martin K.N Siele in Nairobi