The Facts

A regulatory crackdown has contributed to a deep freeze in dealmaking.

The U.S. Federal Trade Commission and its fellow antitrust cop, the Justice Department, are scrapping decades of precedent in challenging mergers, and are joined by an increasingly global regime that is rewriting the rules of corporate consolidation.

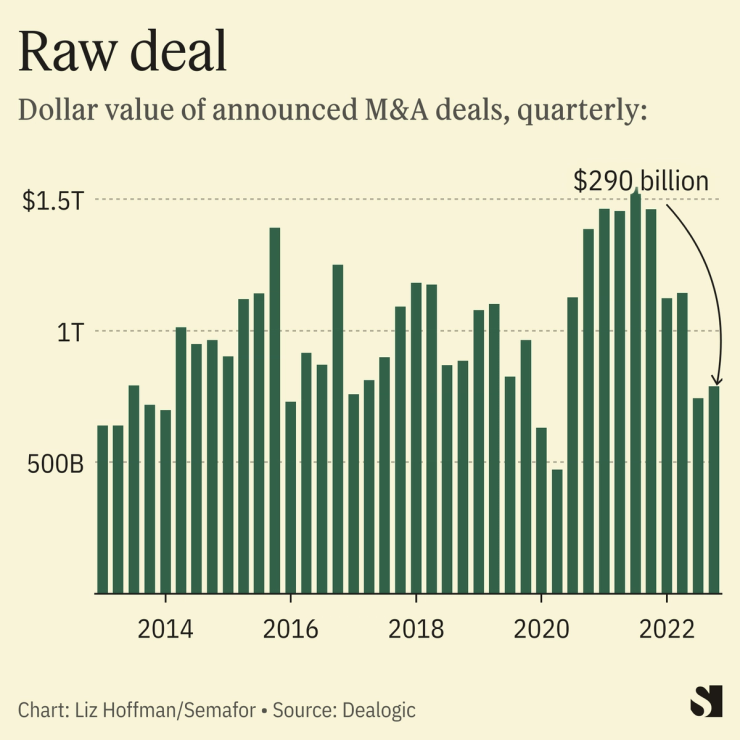

Global mergers fell 37%, by dollar value, last year from 2021’s record high, according to Dealogic, the biggest annual drop since the dot-com bubble burst. While much of that can be blamed on recession fears and higher interest rates, which make takeovers more expensive, governments’ anti-merger turn is partly to blame.

Deals in less-sensitive sectors — read: not tech or healthcare — are still getting done, but advisers say most of the activity these days is in smaller corporate carve-outs like food giant Post selling its dairy line (that and a few more scooplets from my notebook below.)

The Scene

In December 2020, the owner of Bass Pro Shops thought it had reeled in a big deal — an agreement to buy outdoor retailer Sportsman’s Warehouse for $785 million.

In private conversations with the companies’ management, antitrust regulators in Washington suggested the deal could be approved with a few small adjustments, likely by selling a handful of stores in places where the companies overlapped, people familiar with the discussions said.

Then came regime change. After Lina Khan was sworn in as head of the FTC the following summer, she ordered a fresh review of the deal and eventually overruled her staff, the people said. Told they would have to sell up to a third of Sportsman’s Warehouse stores, the companies abandoned the deal instead.

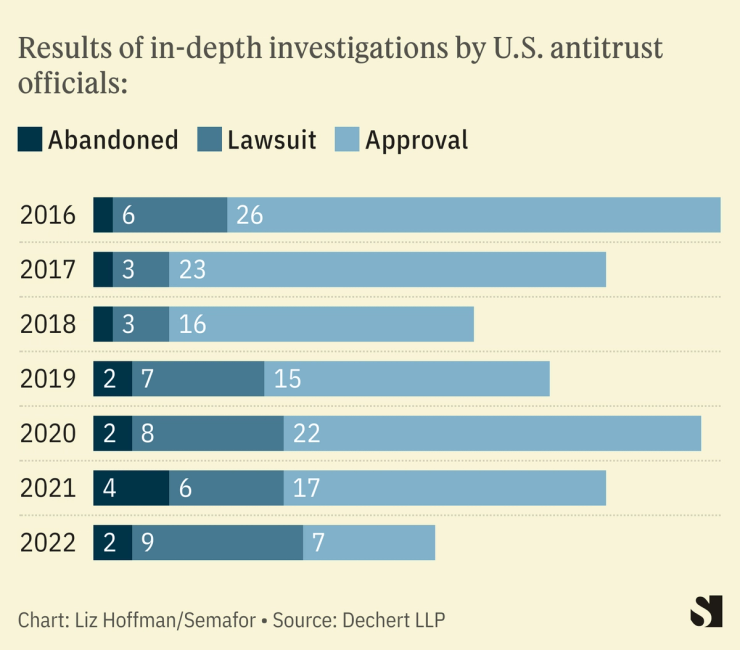

It became one of at least 35 transactions that were abandoned or blocked on antitrust grounds since the Biden administration took office, according to law firm Dechert. Every investigation that wrapped up in the third quarter of 2022 ended with a scuttled deal.

And in another break from the past, officials aren’t accepting divestitures or other potential fixes. “This administration is not afraid to bring cases it might lose,” said James Fishkin, an antitrust lawyer at Dechert who tells companies they “have to be prepared to litigate.”

Know More

Procter & Gamble nixed its purchase of razor maker Billie. Two semiconductor giants, Nvidia and Arm, scrapped their deal. So did two New Jersey hospitals and two Finnish crane operators. Microsoft will defend its $69 billion takeover of Activision — the largest tech merger of all time — in court later this year. And regulators are said to be preparing to block deals for Spirit Airlines, mortgage-data company Black Knight, and software-collaboration app Figma. Unlike prior administrations, this one isn’t afraid to lose in court.

It’s not just antitrust regulators. CFIUS, the U.S. panel that reviews deals for national-security concerns, has also been taking a closer look. (See our recent story on Forbes’ scramble to replace its currency lead investor, an Indian billionaire with ties to Moscow, with an American.)

Here’s what else you can buy, if you’re so inclined.

- Hello Bello, the baby-care company founded by celebrity couple Kristen Bell and Dax Shepard, is shopping its $200 million in 2022 sales and star power to a buyer or new investor, according to people familiar with the matter. The celebrity halo has worked well for some, like Reese Witherspoon’s production company, and less well for others, like Jessica Alba’s Honest Co.

- Post is selling its Crystal Farms cheese brand, with about $200 million in sales, according to people familiar with the matter. (Elsewhere in milk, Danone has hired Centerview to sell its Horizon Organic arm, which accounts for about 3% of the conglomerate’s global sales.)

- Bankers are shopping privately-held Life Alert, of the “I’ve fallen and I can’t get up” TV commercials, a bet on aging boomers, a person familiar with the matter said. For a different generational wager, VF Corp. is selling its iconic — to millennials, anyway — JanSport backpack brand, Bloomberg reports.

Liz’s view

Regulators should rightly be skeptical, especially now after an eight-year cycle of corporate consolidation. But the recent crackdown has a political, rather than technocratic, feel.

In exchange for its approval of Cargill’s takeover of Sanderson Farms, the Justice Department extracted concessions on labor practices that had been under investigation — not unimportant, but not traditionally part of the merger review process.

Advisers say private-equity firms — a political villain among liberals — have been questioned about how much debt they use and whether their portfolio companies have non-compete clauses for their employees, another priority of the FTC.

And officials don’t always get the substance right. In 2016, the FTC blocked a deal between Staples and Office Depot, arguing that it would reduce competition in brick-and-mortar office-supply stores – which it would have. But the companies said that analysis ignored the rise of e-commerce. Amazon has since gone heavily into the office-supply business.

Room for Disagreement

Sometimes they do. Blocking AT&T’s acquisition of T-Mobile in 2011— and the resulting breakup fee AT&T owed the smaller company — bolstered a low-cost competitor and helped spark the wireless price wars of the mid-2010s.

And regulators are right to be skeptical of the easy fixes that companies often propose to get their deals through. To get the FTC’s blessing for its takeover of Dollar Thrifty, Hertz spun off its Advantage rental arm to private equity. It promptly went bankrupt.

Step Back

Regulators have trotted out new legal theories in their crackdown.

The DOJ blocked the sale of Simon & Schuster not because it would harm the book-buying public — the traditional “consumer harm” theory of antitrust — but because it would harm authors by reducing competition for their manuscripts. (Stephen King testified for the government.)

That argument could be deployed in what is likely to be a series of antitrust cases against Silicon Valley giants. It’s hard to argue that their products, which are free and wildly popular, are bad for users from a price perspective. But their grip over the advertising market hurts other players in the ecosystem, notably media buyers and publishers.

The View From Helsinki

Merger scrutiny is now effectively a global regime, with countries reserving the right to block deals that only tangentially touch their domestic economies.

Consider the merger of two Finnish crane companies that sailed past the European Commission, only to be abandoned after British and U.S. officials said they would block it.

The U.K. has been flexing its regulatory muscles since its divorce from the European Union gave it deal-blocking power.

Or consider the tie-up of two biopharmaceutical companies, one British and one the U.K. subsidiary of a Chinese firm, which has been delayed as it works through “potential national security risks” with CFIUS.

Notable

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce recently sued to unseal correspondence between American and foreign antitrust officials, arguing unfair coordination between the agencies in blocking Illumina’s takeover of cancer blood-testing startup Grail.