The Scene

LONDON — A young man gazes out of a poster on the side of a bus stop. He’s pointing, as if wagging his finger in admonishment, underneath a four-letter word: “Japa.” It’s a slang word in the Yoruba language predominantly used in southwest Nigeria that means “escape” or “flee.”

But the bus stop is in London, not Lagos. The term “japa” has become widely used among Nigerians to describe the large-scale migration of young people from the West African country to wealthy nations in recent years. The United Kingdom, United States, and Canada tend to be the most popular destinations for Nigerians typically leaving home in search of work and education opportunities.

Nigeria’s rapidly rising cost of living and a lack of job opportunities have created a sense of desperation that has driven people to seek opportunities beyond those traditional destinations, in places like eastern Europe and Australia.

The tagline for the London bus stop advertising campaign, which is run by remittance company TransferGo and helps to explain the finger wagging gesture, is simple: “But never forget home.” The implication is that it’s fine to leave Nigeria, but remember to send money back to your family.

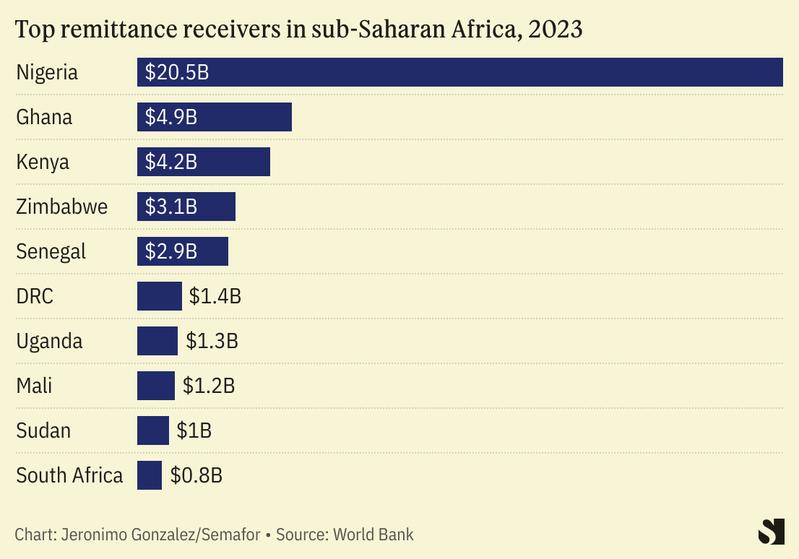

Newly released World Bank data shows $20.5 billion was sent to Nigeria last year, which meant it accounted for around 38% of total remittance inflows to sub-Saharan Africa. And inflows have steadily increased, up from $20.1 billion in 2022.

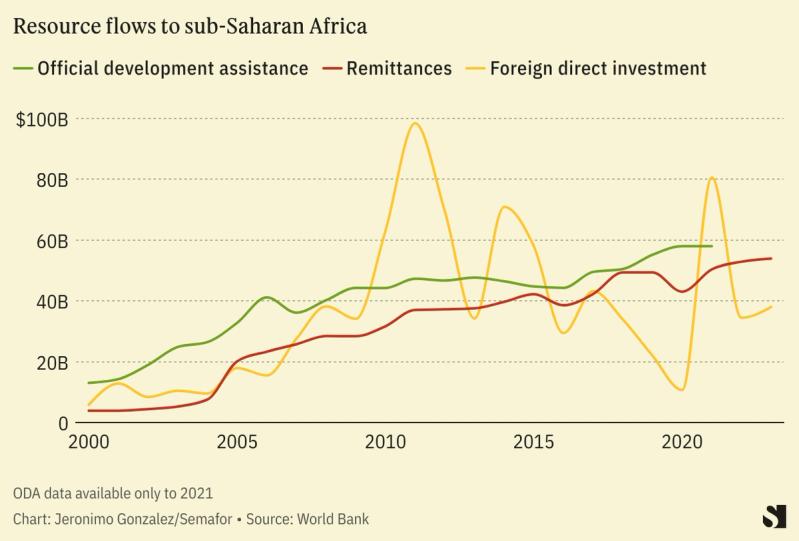

By comparison, the bank’s data showed that in 2022 overseas investors took out $186.8 million more from Nigeria’s economy than they put in. That continued a trend which has seen remittance flows to Africa’s biggest economy dwarfing foreign direct investment in recent years.

Know More

Global remittances were for decades dominated by industry giants Western Union and MoneyGram. But the proliferation of tech companies, along with greater adoption of mobile wallets, has increased competition from companies such as 11-year-old TransferGo which began serving the Nigeria market around two years ago, to much smaller fintech players across Africa and Europe. The japa phenomenon has opened up a chance to tap into the market for people sending money to Nigeria, a country of more than 200 million people.

“Nigeria is the biggest market we serve in Africa,” Bamiyo Awonusi, TransferGo’s London-based marketing manager, told Semafor Africa, adding that the campaign was run in the last few months along bus routes passing through communities with large Nigerian populations in the British cities of London, Manchester and Birmingham. “The fact that people are leaving en masse to the USA, Europe, and Canada means that there is potential for remittance companies,” she said.

The skyrocketing inflation and high unemployment that spawned the japa wave has also intensified the needs of people who remain in the country and rely on relatives overseas to send money typically used to help pay bills.

Remittance flows to sub-Saharan Africa totalled $53 billion in 2022, which marked a 6.1% increase from the previous year.

Remittances outstrip foreign direct investment and overseas development aid to such an extent that some African governments increasingly see it as a vital source of foreign currency.

Alexis’s view

The surge in competition for the Nigerian market in the remittance corridor connecting Africa’s largest economy and the United Kingdom makes sense in light of the japa phenomenon. The trend is evident in the marketing battle playing out on the streets of London — particularly on public transport routes that cut through communities with large West African immigrant communities.

Panjak Sharma, executive vice president of Nasdaq-listed remittance processor Remitly, told me that “remittances trends, very nicely map to the general immigration trends that we see.”

With a higher cost of living in advanced economies in recent years, due to high inflation and interest rate rises, migrants have less money to send home than before. That’s reflected in a slowdown in the rate at which remittance flows have grown. So it makes sense to target those from Africa’s most populous country at a time when those who can find a way out are leaving.

The fact that the disposable income of migrants has dwindled, combined with intense competition in an increasingly crowded field of companies, explains the need to splash out on clever marketing.

David Omojomolo, Africa economist at Capital Economics, said remittances were a “vital” source of foreign currency at a time when Nigerian authorities are struggling with a dollar scarcity that has caused the value of the naira to plummet. But he stressed that it should be one element of a more diversified economy. “Remittances will help but the focus should clearly be on exporting.”

Room for Disagreement

Funds that come via the black market aren’t captured, which means only a small segment of remittances are fully reflected in data relating to countries like Nigeria where there is a massive parallel market.

Benjamin Fernandes, the Tanzanian founder and CEO of East African fintech NALA, argues in a blog published last month that official figures underestimate the extent to which people exchange money through informal routes such as hawala networks in the Somali diaspora communities, whereby money is given to someone at an agreed rate and they deliver cash to the intended recipient.

“The potential to advance technological infrastructure in consumer industries like remittance is still largely untapped,” he argues.

The View From Nairobi

Kenya’s President William Ruto is seeking to grow Kenya’s remittances to $10 billion a year from around $4 billion, primarily by securing jobs abroad for Kenyans. The government aims to create one million jobs overseas a year to boost its foreign currency reserves as well as diaspora remittances.

Marshel Nyangor, a fund manager at Nairobi investment firm Zimele Asset Management, said the government should instead incentivize investors and manufacturers to create more local jobs. “Countries generally don’t grow their economies by exporting their young, energetic labor force,” he told Semafor Africa. “I would prefer they incentivize job-creating sectors like manufacturing by bringing down the cost of production, in particular the cost of energy.”

— Additional reporting by Martin Siele in Nairobi

Notable

- Global fintech companies sometimes cut off African users from their services. And sub-Saharan Africa remains the region with the highest remittance costs. But a raft of African companies offering to make cross border payments faster and cheaper have sprung up, reports Rest of World.