The News

The House Republican meltdown is fueling fears that the caucus won’t be capable of raising the debt ceiling later this year, potentially sparking a global financial crisis.

The GOP holdouts blocking Rep. Kevin McCarthy’s speaker bid say they want assurances that he won’t allow a vote to raise the government’s borrowing limit without securing major policy concessions from Democrats, like a path to a balanced budget.

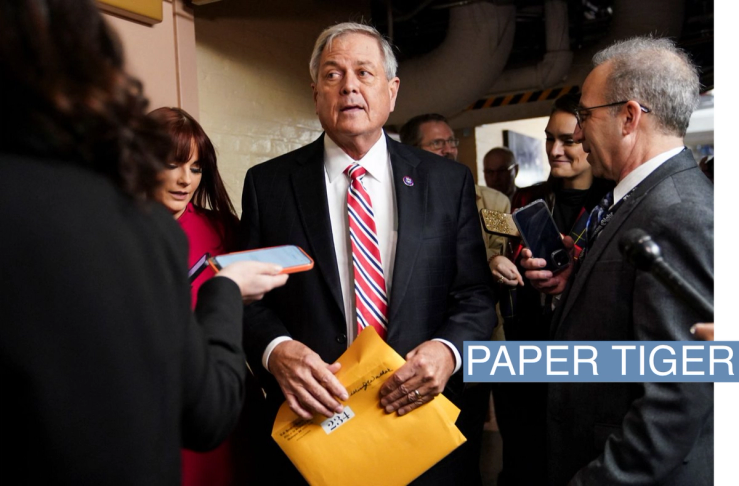

“Is he willing to shut the government down rather than raise the debt ceiling? That’s a non-negotiable item,” Rep. Ralph Norman, R-S.C. told reporters, according to Bloomberg.

McCarthy ally Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene, R-Ga. also told reporters on Wednesday that some members had discussed adding conditions to a debt limit increase, like fiscal reforms or spending caps, in order to elect a speaker.

“Obviously spending is a very important issue, especially to conservatives like me,” said Greene. “That has been a part of our conversation.”

After watching conservatives unite to tank McCarthy’s bid or browbeat him into obedience, Democrats are worried that the next Republican speaker — whoever it might be — will have no choice but to go along with the hardliners’ demands, potentially leading to a risky standoff between the parties. But beyond that, they’re concerned that the House GOP has become so dysfunctional that it might not be able to raise the debt ceiling under any circumstances.

“Are people actually going to get to the place where they’re sabotaging the country to make a political point?” asked Democratic New Jersey Rep. Andy Kim. “What I’m witnessing here, over the last 24 hours, is making that much scarier to me.”

In this article:

Benjy’s view

You can print this out to humiliate me later, but my best guess is that the same divisions roiling the House will also prevent it from mounting a serious debt ceiling fight that extracts major concessions.

Unlike the 2011 debt limit negotiations that took place after the Tea Party wave, Democrats are unlikely to concede the premise that they should trade anything at all in return for raising the debt limit. Senate Democrats feel they successfully raised the debt ceiling while offering Republicans little in 2021, and seem inclined to repeat that strategy.

“In exchange for keeping the lights on, they get nothing. In exchange for lifting the debt ceiling, they get nothing,” Sen. Brian Schatz, D-Hawaii told Semafor. “We must not make policy concessions if their starting point is doing violence to the American financial system.”

It’s this position that has some worried about a breach, of course — if Democrats underestimate Republican resolve, they could sleepwalk into a crisis at the last minute with no way out.

But the party pushing for major changes in shutdown fights or similar standoffs typically starts at a huge political disadvantage already. A divided caucus that limped through the midterms without a clear mandate has even less leverage. Maintaining 218 votes on a clear, consistent, and achievable position would be critical to success — and very unlikely, especially after this week’s fiasco.

Moderates are already openly contemptuous of the conservatives driving the anti-McCarthy rebellion. It seems hard to imagine them sitting quietly while the same hated colleagues lead a no-compromises charge for, say, a rapidly balanced budget filled with unpopular cuts while the stock market begins to tank. This is especially true since the core of the razor-thin majority — some 18 members — are in vulnerable seats won by Biden. Several come from New York and New Jersey, where Wall Street firms with no interest in watching the bond markets burn hold political sway.

If a speaker can’t credibly promise to deliver 218 votes on a deal without help from the other side, their leverage withers. Faced with similar internal splits, former speakers like John Boehner and Paul Ryan were forced to turn to Democrats to get must-pass bills across the finish line.

A plausible endgame is that House leadership ends up having to accept a bipartisan deal crafted in the Senate with some kind of fig leaf — say, a commission to study future spending cuts — that leaves conservatives disappointed, similar to the recent omnibus bill.

Of course, saying yes to such a deal could put the speaker’s job in jeopardy yet again. But even in that scenario, it would take only a small handful of moderates to join Democrats on a discharge petition rather than tank the economy or oust yet another leader in order to appease their most loathed colleagues.

One more point a House Democratic aide raised: Whether or not Democrats expect the debt limit threats to ultimately fizzle out, it’s in the party’s interests now to portray Republicans as out-of-control extremists ready to burn the economy down in order to build pressure for a solution further down the line. So while much of the concern is genuine, there is a kayfabe element to keep in mind.

Room for Disagreement

Philip Klein at National Review argues that a weak majority captured by the hard right and a Democratic administration unwilling to negotiate could still do plenty of damage before they strike a deal. “Most likely, the only way this ends is with a significant meltdown in financial markets that forces the hand of Congress,” he writes.

— David Weigel, Kadia Goba, and Jordan Weissmann contributed