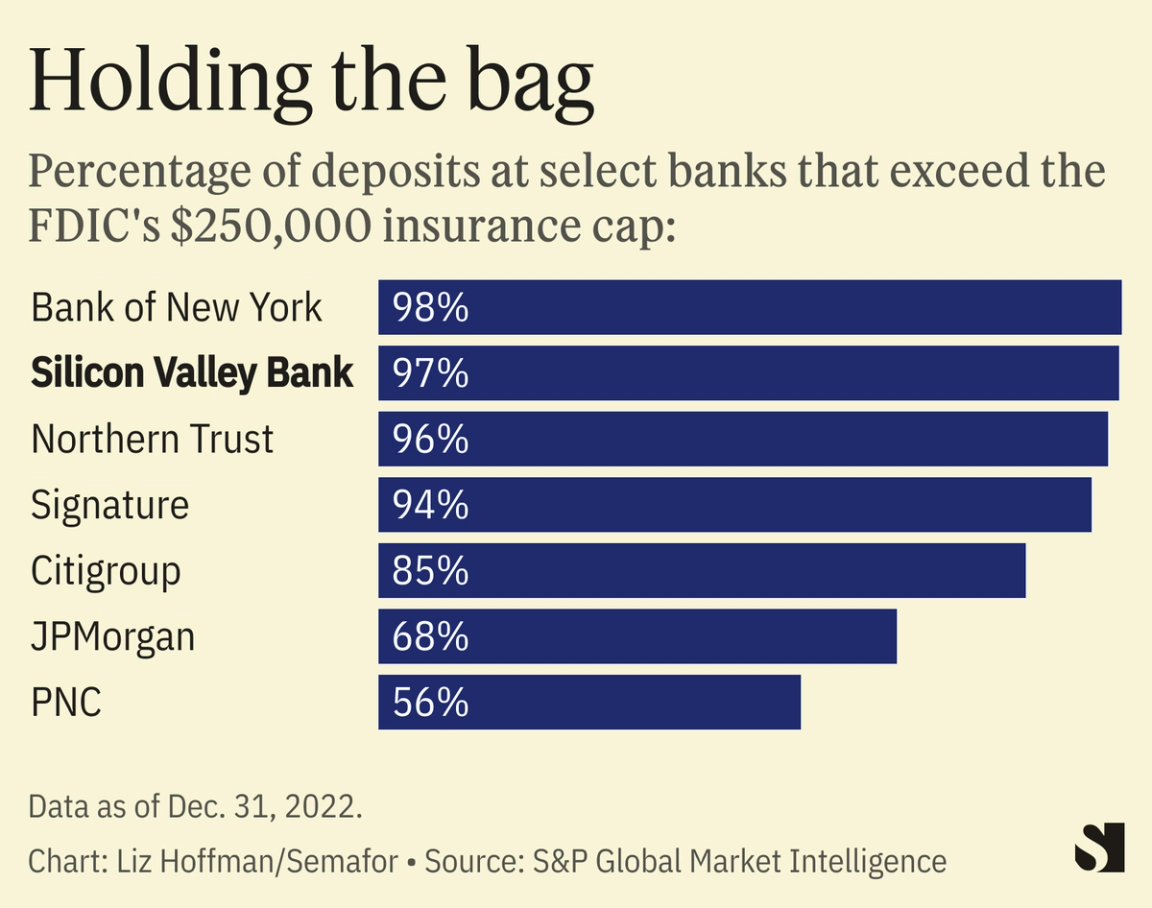

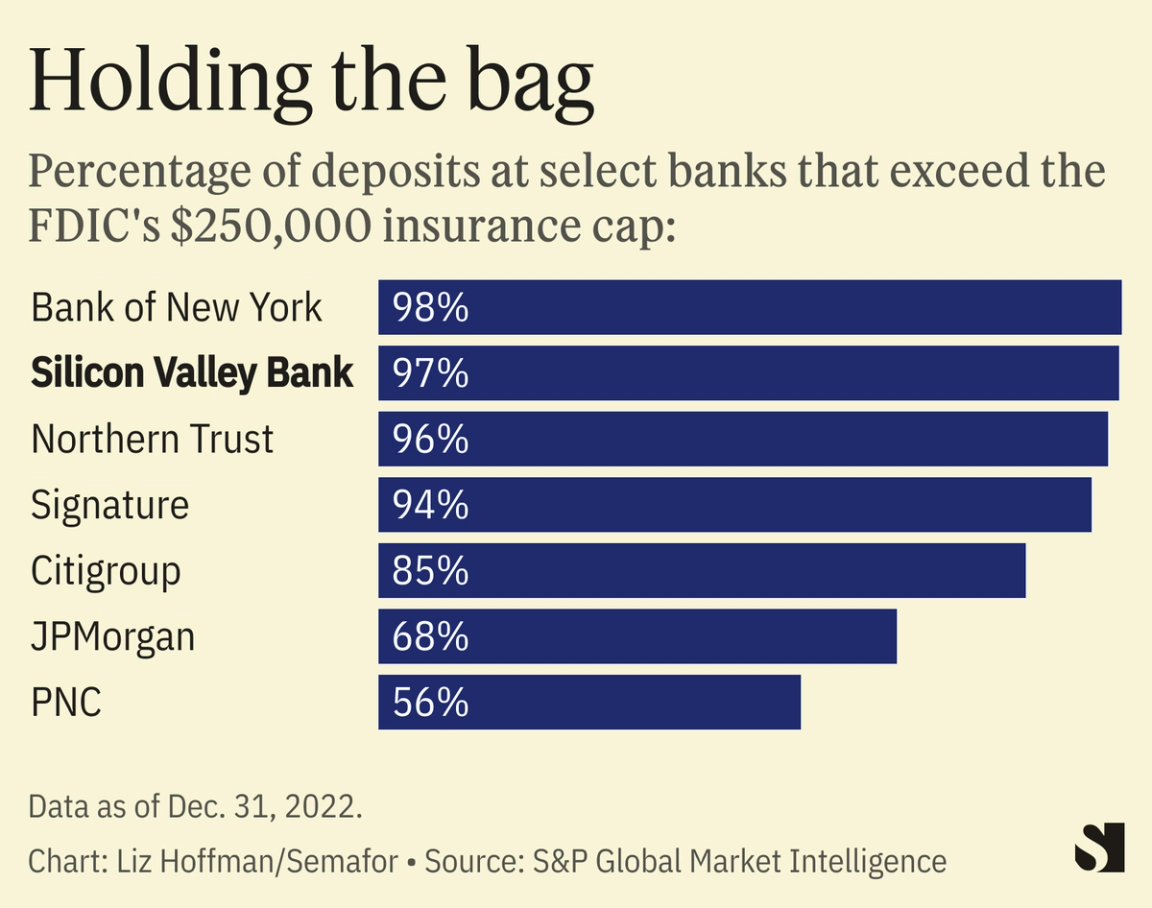

Reuters/Nathan Frandino Reuters/Nathan FrandinoTHE SCOOP Hedge funds are offering to buy startups’ deposits stranded at Silicon Valley Bank for as little as 60 cents on the dollar, pitching expensive but crucial lifelines to founders unable to access their cash after the lender collapsed yesterday, people familiar with the matter said. Firms better known for investing in distressed debt, including Oaktree, one of the people said, are fanning out to startups in the wake of the bank’s failure and seizure by the Federal Insurance Deposit Corp. on Friday. Its collapse left hundreds of startups — as well as the venture funds that backed them — unable to access their cash to meet payroll and other expenses. Bids range from 60 to 80 cents on the dollar, the people said, reflecting a range of expectations for how much of the uninsured deposits — those that exceed the FDIC’s $250,000-per-customer cap — will ultimately be recovered once the bank’s assets are sold or wound down. About 96% of SVB’s deposits as of Dec. 31 were uninsured, according to the bank’s filings, far higher than a typical lender. That reflects its concentration of tech-company clients, which deposited their venture fundraising hauls of the past few years. It also amplifies the risk of a bank run like the one that pushed SVB into failure; depositors who realize their money isn’t backstopped by the government are faster to yank it out. The bank was slammed by $42 billion in withdrawals on Thursday, leaving it with a negative cash balance of about $958 million by the end of the day, according to California’s financial services regulator, the primary watchdog for SVB. The FDIC said it would advance some money to uninsured depositors next week. Law firm Cooley told clients in a Friday evening call it expected that would cover about half of their deposits over the $250,000 cap, and that the FDIC had already been selling SVB’s more liquid assets, like Treasury bonds, according to an attendee. Oaktree and others are offering startups cash now to pay urgent expenses, but at a steep discount, with the goal of eventually receiving more from the FDIC later, possibly in weeks or months, and pocketing the difference. Brex, a financing startup that caters to other startups, on Friday said it would offer emergency loans to cash-strapped companies.  LIZ’S VIEW The FDIC may end up having to waive the deposit insurance cap and make everybody whole to avoid a broader run. First Republic, Western Alliance Bank and other lenders popular in Silicon Valley are facing withdrawals and have been trying to calm investors and depositors. It will look to many like a bailout with uncomfortable echoes of 2008. But the “moral hazard” argument is different here. People with savings accounts can’t be expected to monitor their banks’ financial health, and even the tech companies that make up a large part of SVB’s depositors can’t be expected to be experts in bank balance sheets. Making depositors whole will ensure the losses are borne by professional investors — SVB’s bondholders and stockholders — whose job is to evaluate financial risk. ROOM FOR DISAGREEMENT Keith Noreika ran the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, which regulates some of the country’s biggest banks, during the Donald Trump administration and cautioned against a bailout of depositors, warning it might even be illegal. He told Semafor: “The FDIC and Fed had the chance to save the bank by allowing it to merge or finding a buyer for it, as they’re permitted by law to do. Had they done so, no uninsured depositor would be at risk. Instead, due to strong political pressure against merger approvals from the far left, they hesitated. Now they’re faced with the prospect of a full government bailout of uninsured creditors after the fact — which I am not even sure is permitted by law — and which could be quite expensive and set the future precedent that all deposits are insured, giving rise to moral hazard.” |