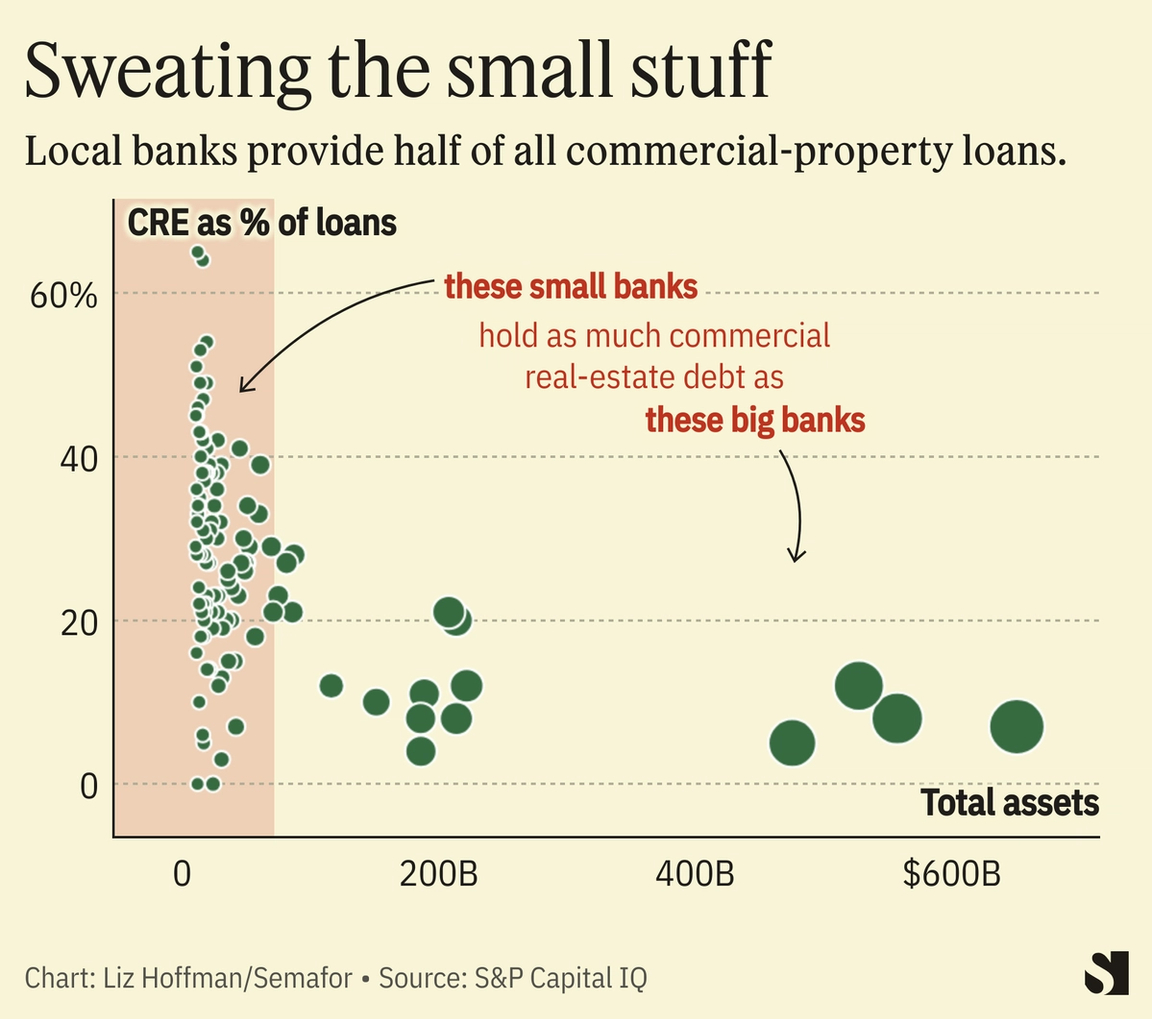

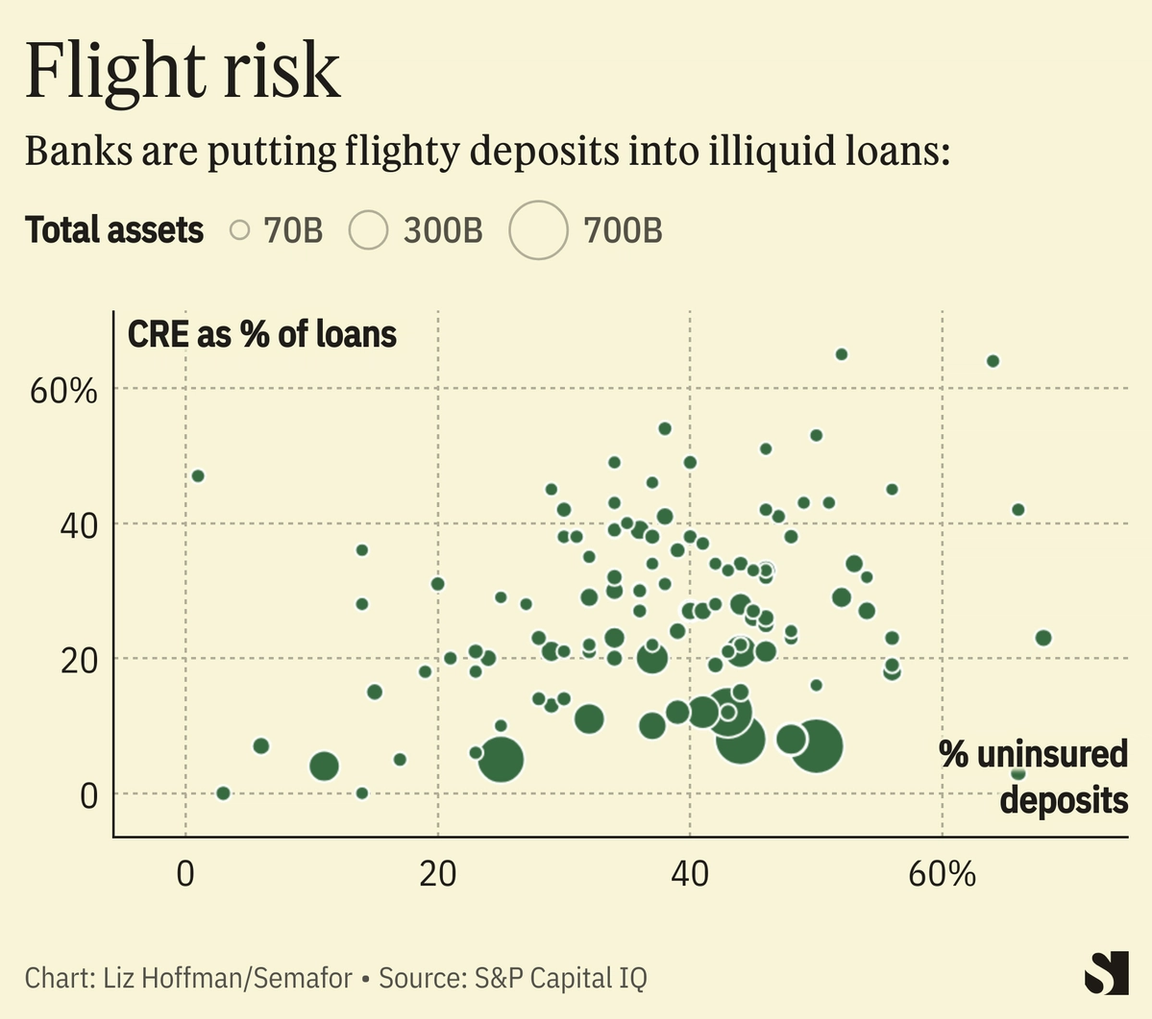

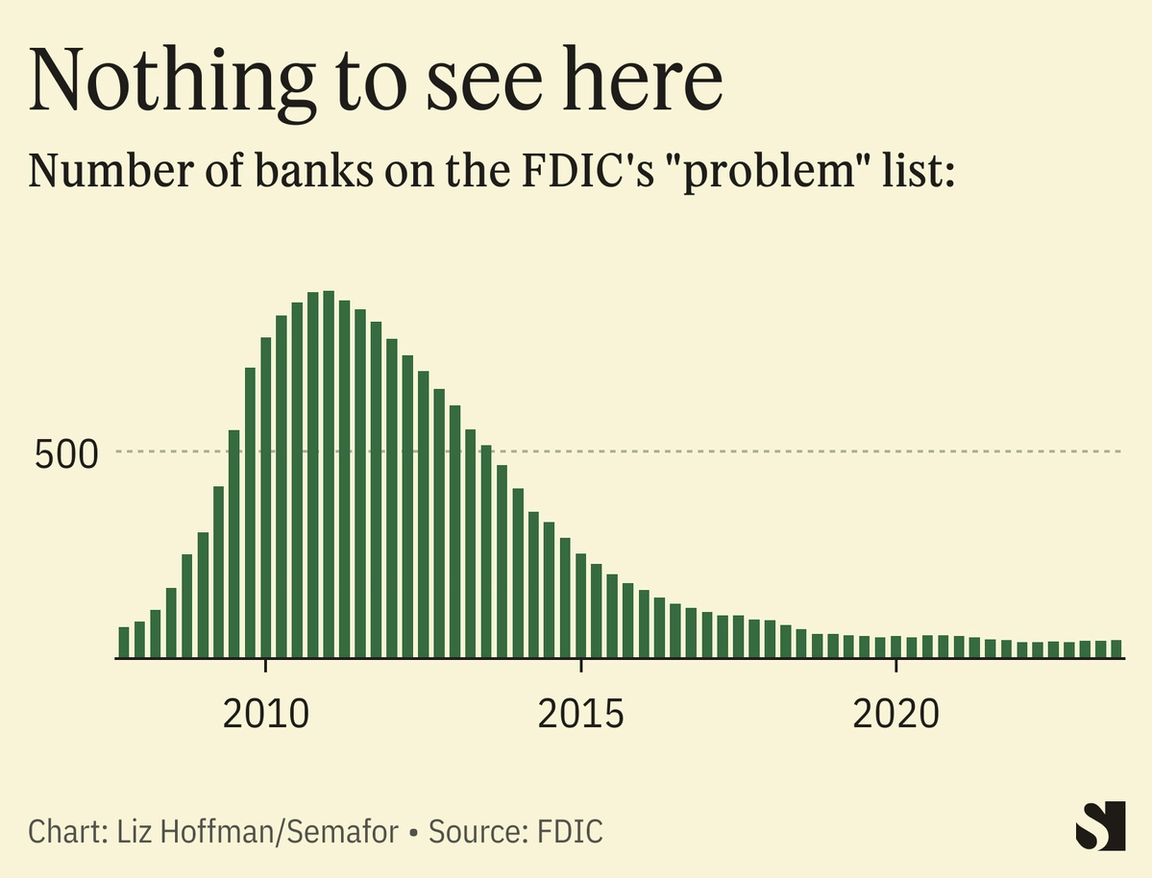

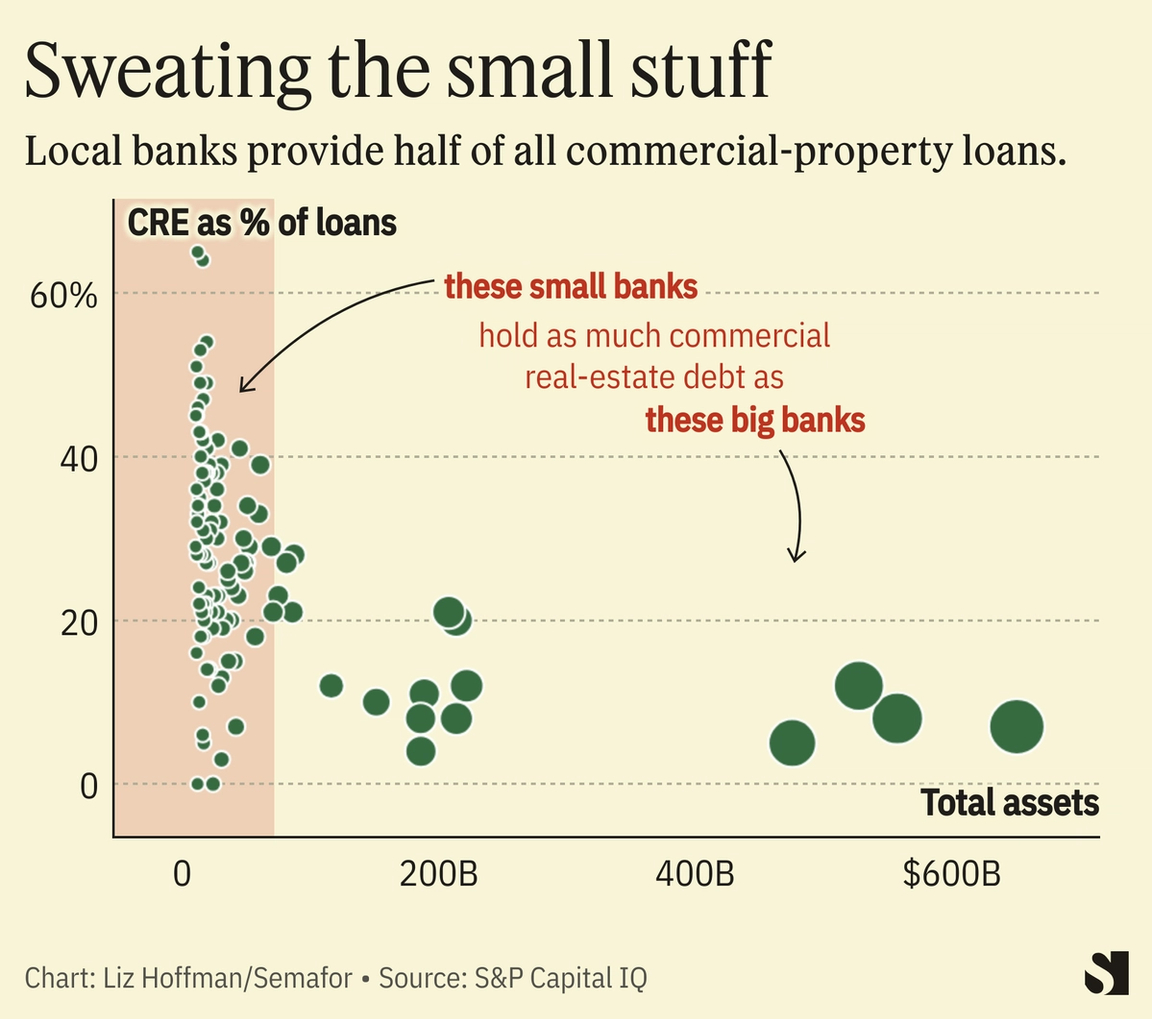

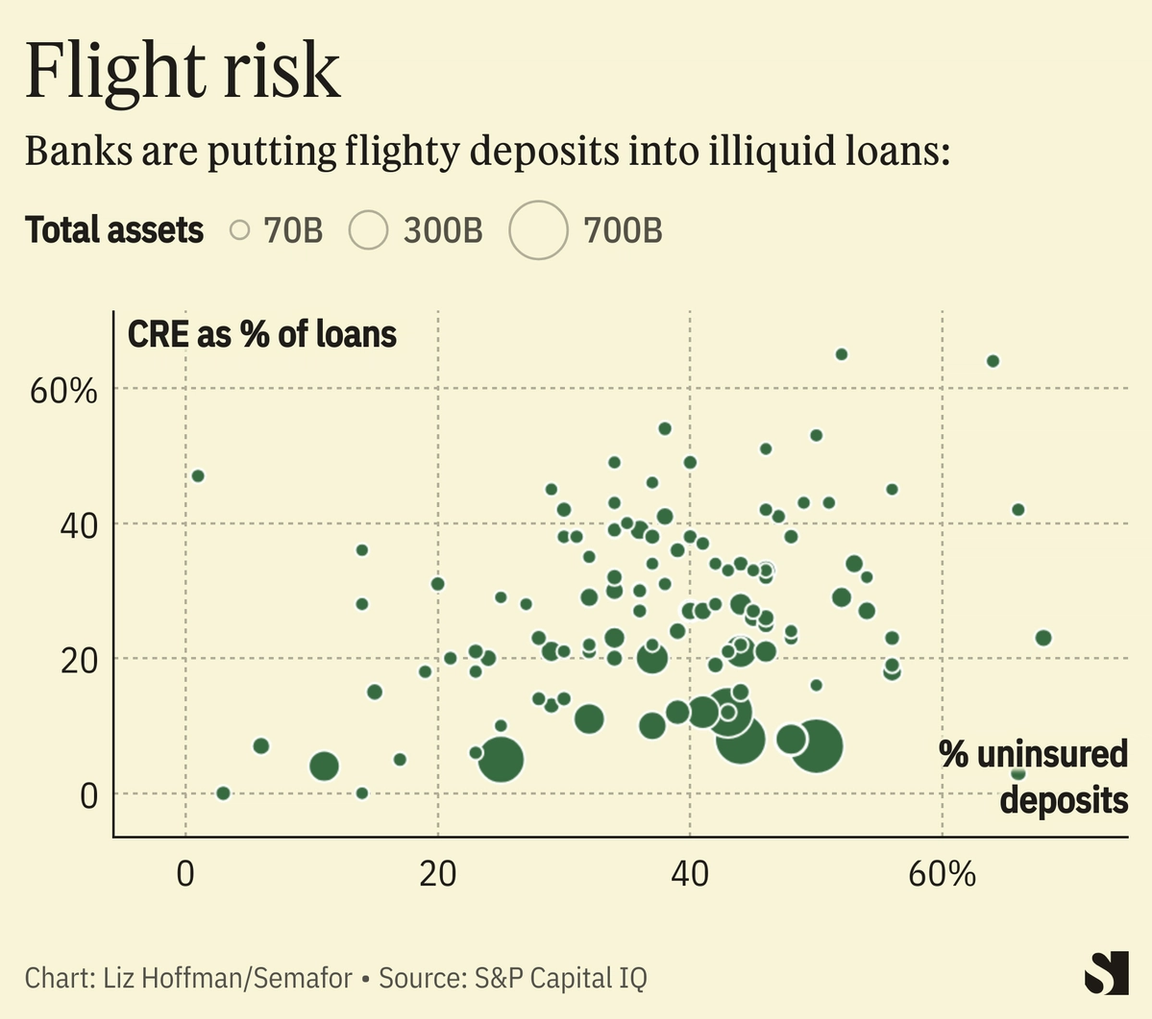

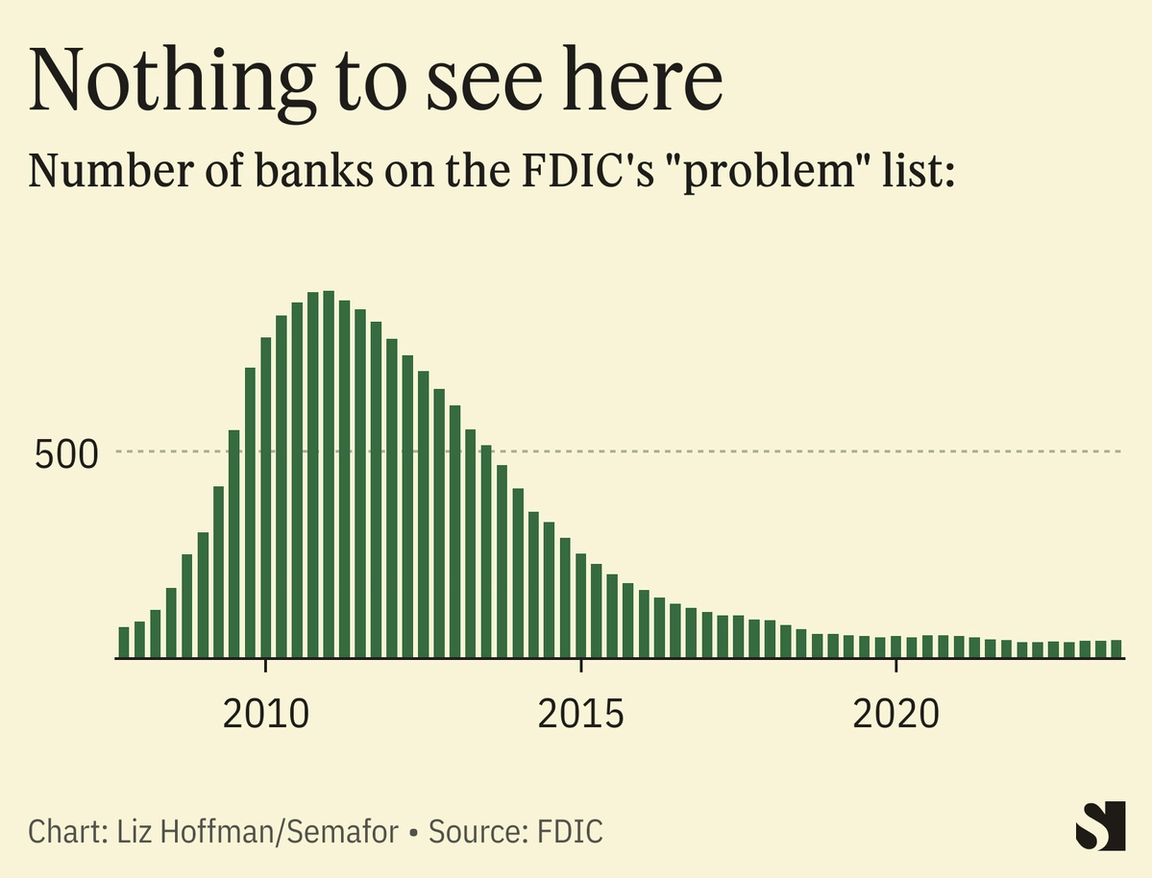

THE SCENE Almost a year after the failure of three midsized U.S. banks sparked an industry crisis, investors and regulators are once again bracing for turmoil among regional lenders, this time due to rising defaults in commercial mortgages. The tipping point may be a Long Island lender, New York Community Bank, that reported major losses on its real-estate loans last week. NYCB’s share price has dropped 60%, dragging stocks of other regional banks down with it in an uneasy echo of last spring, when the government was forced to throw emergency lifelines to keep the system from toppling. NYCB was initially a benefactor of those failures, scooping up Signature Bank last year after it was shut down by regulators following a run on deposits. KNOW MORE The culprit now is commercial real-estate debt, which is souring quickly as landlords face higher interest rates than they can afford and tenants, after nearly four years of half-full offices, are cutting their leases. And while the U.S. banking system is increasingly dominated by a handful of national giants, commercial mortgages are still the province of regional lenders.  Commercial mortgages account for, on average, 3% of the assets at the 10 biggest banks in the country. At the next 150 banks, it’s almost 20%. Local banks routinely have half of their customers’ deposits tied up in mortgages for office buildings, hotels, and malls. By NYCB’s own account, 44% of its entire loan book is mortgages to apartment complexes, half of that to rent-stabilized units whose landlords are struggling mightily as their own costs rise. The deposits these banks rely on are a flight risk because more of them exceed the government’s $250,000-per-account insurance limit. As we saw last spring, uninsured deposits are the first to go, which can quickly leave banks insolvent.  LIZ’S VIEW This is more concerning than what happened last spring. The problem then was a handful of banks doing something they weren’t really supposed to be doing at all (buying a lot of long-dated bonds) and doing it stupidly (not protecting themselves from the financial hit of swiftly rising interest rates.) Not great, but easy enough to blame on greedy management and flat-footed regulators. The banks in trouble now got there by doing exactly what they were supposed to do and doing it badly. We don’t need banks to own a lot of Treasury bonds — individuals can do that for themselves — but we do need them to finance New York City office buildings and solar farms and startup businesses. Put another way, the banks that collapsed last spring mostly failed because the pandemic caused a lot of things to happen that had never happened before. Savings accounts swelled, inflation skyrocketed, and the U.S. Federal Reserve raised interest rates at a record pace. Silicon Valley Bank basically misjudged Fed Chair Jerome Powell. But banks like NYCB are now teetering because they misjudged their own borrowers, and either made loans to businesses that weren’t creditworthy or didn’t charge them enough interest to compensate for the risk. That’s the basic job of a bank, and gives this turmoil a more uneasy flavor than last time. One other note: There’s also a real risk of embarrassment here for regulators, who deemed NYCB strong enough to buy the remains of another failed bank last spring. For Moody’s to find “multi-faceted financial, risk-management and governance challenges” just a few months later isn’t a good look for regulators. ROOM FOR DISAGREEMENT Banks fail because they can’t sell assets quickly enough, and there’s likely to be ample demand — at steep discounts of course, but looming insolvency resets expectations quickly — for troubled bank loans. Private-equity firms were sitting on $550 billion of real-estate funds as of June 30, the latest data tracked by Preqin. There’s also a chance this is more idiosyncratic. Banks have bucked apocalyptic predictions about collapsing margins. The profits they make between what they pay for deposits and what they earn on loans has held surprisingly steady, and the number of banks on the FDIC’s watch list is near record lows.  |