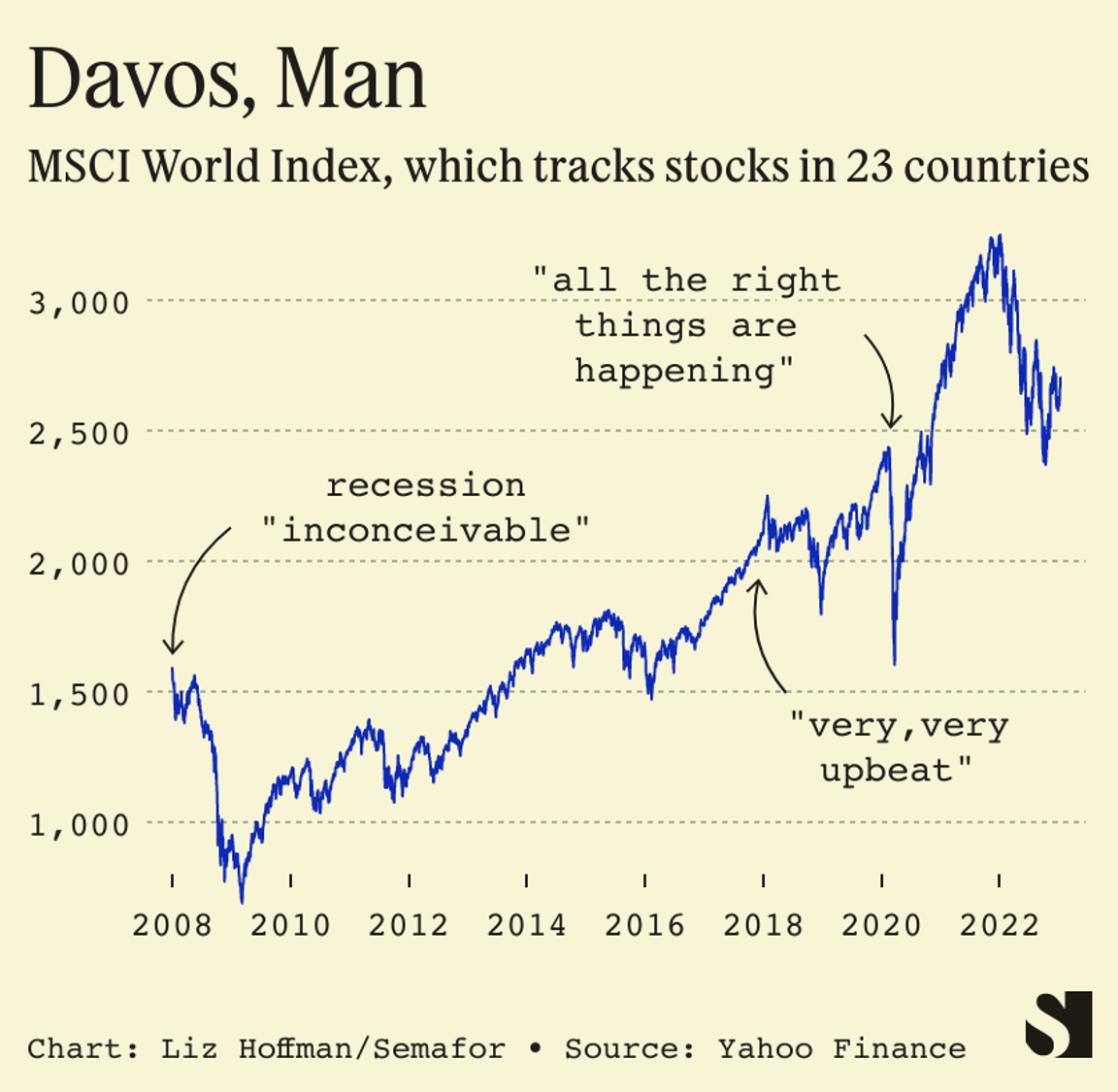

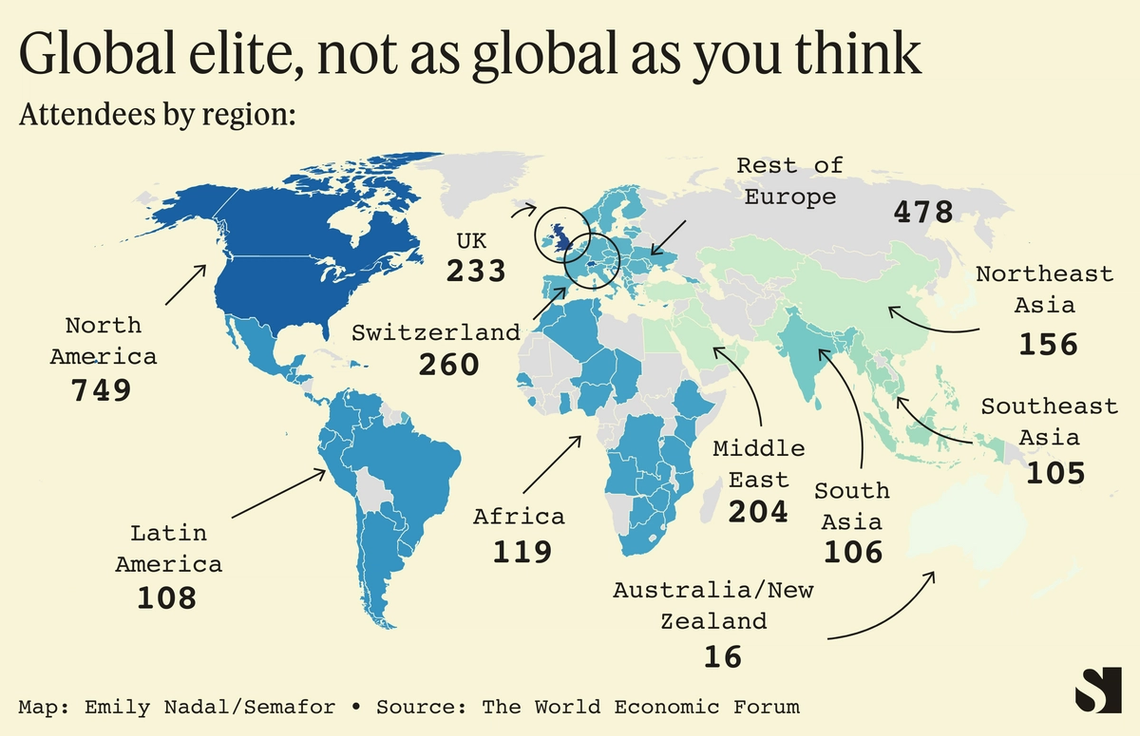

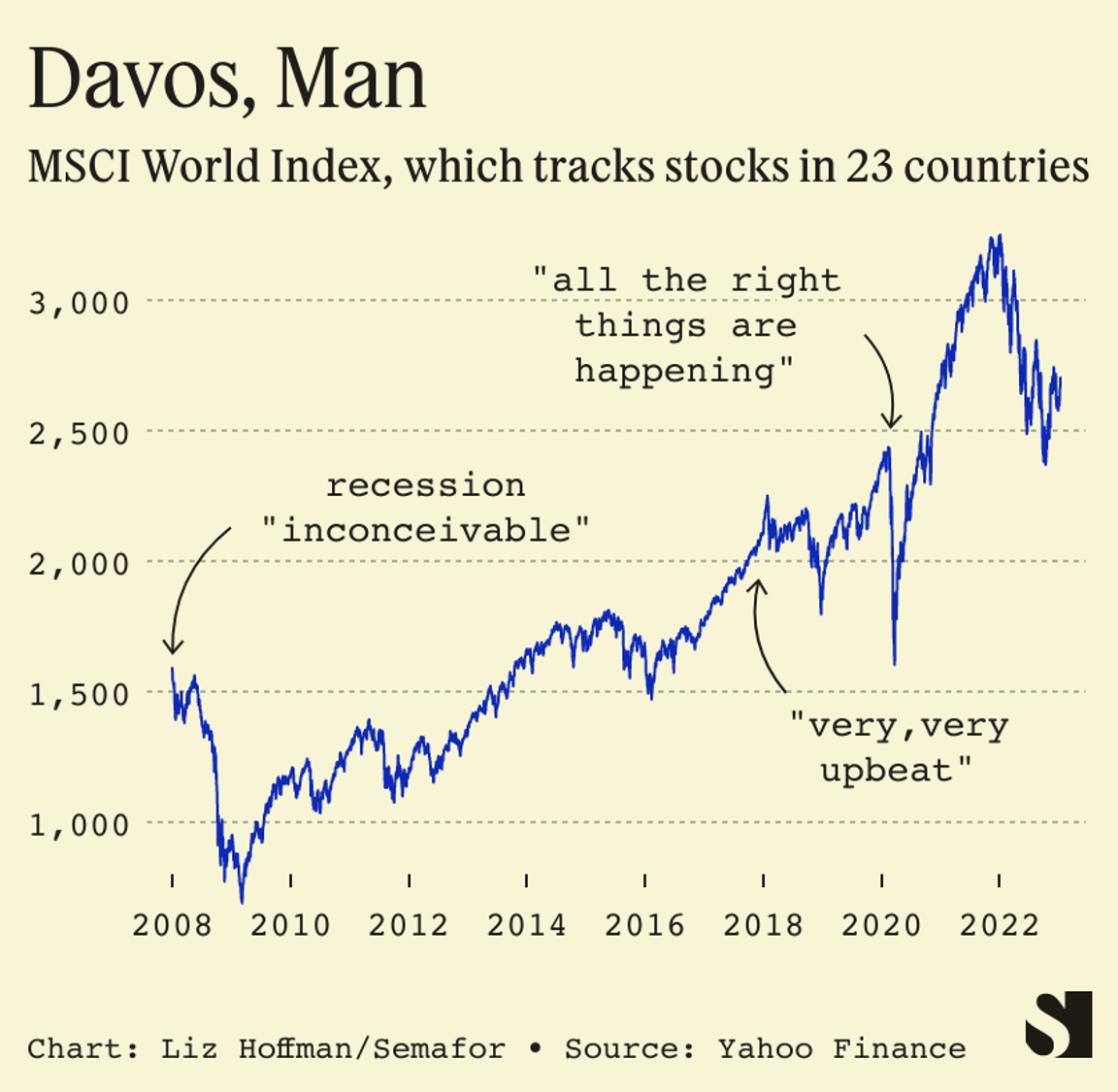

THE NEWS As a potential global recession looms, world leaders and business executives kicked off their confab in Davos yesterday in their first traditional January gathering since the COVID-19 pandemic hit. BlackRock CEO Larry Fink, Chinese Vice Premier Liu He, and U.S. climate envoy John Kerry are expected to attend to discuss the state of the world and offer some solutions. (Notably absent this year: a major Russian delegation, whose party space on the town’s main promenade is now India House.) LIZ’S VIEW There are plenty of legitimate gripes about Davos. It’s elitist. It’s hypocritical. It’s opaque; it shares little about where its $400 million-plus in revenue goes. All fair. My gripe is that it’s wrong, consistently, about important things. In early 2008, as the mortgage crisis was unfolding, C. Fred Bergsten of the Peterson Institute for International Economics told attendees at Davos: “It is inconceivable — repeat, inconceivable — to get a world recession.” Fast forward to 2016, when the conference’s 96-page report on global risks didn’t even mention the two events that would define the turbulence of that year: Donald Trump becoming president of the United States and the U.K. leaving the European Union, despite the fact that both issues were live wires. Trump won his first primary two weeks after the conference wrapped, and two weeks after that, David Cameron scheduled the Brexit vote. “The consensus here is very, very upbeat,” Michael Sabia, who then oversaw $300 billion as the CEO of Canada’s second-largest pension fund, told me in 2018. What followed were two years of slowing economic growth. And of course, 2020. By the time that in year’s conference kicked off, the coronavirus had sickened at least hundreds of people in Asia. The U.S. had confirmed its first case. But not only did the virus fail to prick the sterile gauze of optimism that surrounded Davos, it barely registered at all. As I write in my forthcoming book on the pandemic and its toll on the economy, Davos should have been a warning. Its attendees were CEOs and heads of state, with lines of sight deep into the global economy and the power to shape it. Instead attendees dipped into communal fondue fountains and the crowds were shoulder-to-shoulder at a late-night piano bar. A panel called “The Next Super Bug” spent much of its 40 minutes on the overuse of antibiotics. A pavilion on the promenade rented out for a 300-person dinner co-hosted by Zoom — a company that would become a household name in just a few weeks — was sparsely attended. Welcome to the world’s most expensive echo chamber, where nobody makes friends by being a bummer.  unsplash/Damian Markutt unsplash/Damian MarkuttThe Davos consensus is shaped and refined as the weeklong conference goes on, passed among attendees alongside the plates of toothpicked olives and Gruyère cubes. By Friday it approaches canon. And it is almost always wrong. An investor could do well boiling it down to a few investment theses and building a basket of assets to match — then wagering against it. I’m hardly the first person to have pointed this out. Glenn Hutchins, the veteran investor who delights in needling his peers, says it nearly every year he’s there. He’s not going this year, but shared some thoughts on why he thinks the consensus consistently blows it: “There’s nothing wrong with consensus views, but the key is to ask yourselves, where might we be wrong? Where are the blinders? And Davos isn’t conducive to that. You’re in an intense environment with very little time and very thin air.” The real problem, he says, is the right people being asked the wrong question. “What a potash CEO in Canada can tell me about his next 12 months of production and what that might mean for agricultural production is way more valuable than asking for his views on globalization.” The World Economic Forum itself, in an uncharacteristic spasm of self-awareness, summoned two psychology professors to a panel in 2017 on why people are so bad at predicting the future. In response to the charge that Davos Man is always wrong, one of them had this muted defense: “That’s actually not true…Whether the Davos Man is more accurate than the dart-throwing chimpanzee is another question.” Forecasting is hard. (I was one of those in the packed piano bar in 2020!) But the attendees at Davos aren’t chimpanzees with darts. If they were less blinded by their desire for things to be good, more wisdom might actually come down from the mountains each January.  ROOM FOR DISAGREEMENT There are a lot of smart people at Davos and sometimes they get it right. For example, the World Economic Forum identified “massive digital misinformation” as a major risk in 2013, years before lies weaponized by social media would threaten democracies. And Davos isn’t biased in favor of being wrong, it’s biased in favor of being optimistic and, to a large degree, globalist. That’s an increasingly tough combination as self-interested nationalism and anti-democratic factionalism threaten to undo, in messy fashion, what once looked like a steady march toward a liberal, borderless global economy. Davos was less well-covered in the 1990s, the decade that produced the North American Free Trade Agreement and the euro, but I’d bet the consensus was more on the mark then. Jay Clayton, former chairman of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, has a slightly different view on why Davos Man so often errs. “The middle class does what it wants to do, not what you want to do,” he told me this week. The rarified air, both in the Alps and the lives of the elite, is too disconnected from consumers that power the economy. I didn’t attend last year, but reports from journalists who did suggested that world leaders, humbled by just how badly they’d seen around the corners lately, had all but given up trying. The Wall Street Journal’s James Mackintosh found no consensus among attendees, noting that the world’s confusing stumble out of the pandemic had left leaders each feeling their own part of the elephant, blind to the whole. Some were buoyed by the strength of consumer spending, while others were concerned about gathering geopolitical storm clouds. But neither camp was sure. Ben Smith, Steve Clemons, and I will be bringing you insights from the Alps all week. Just don’t assume any of them will be right. |