The News

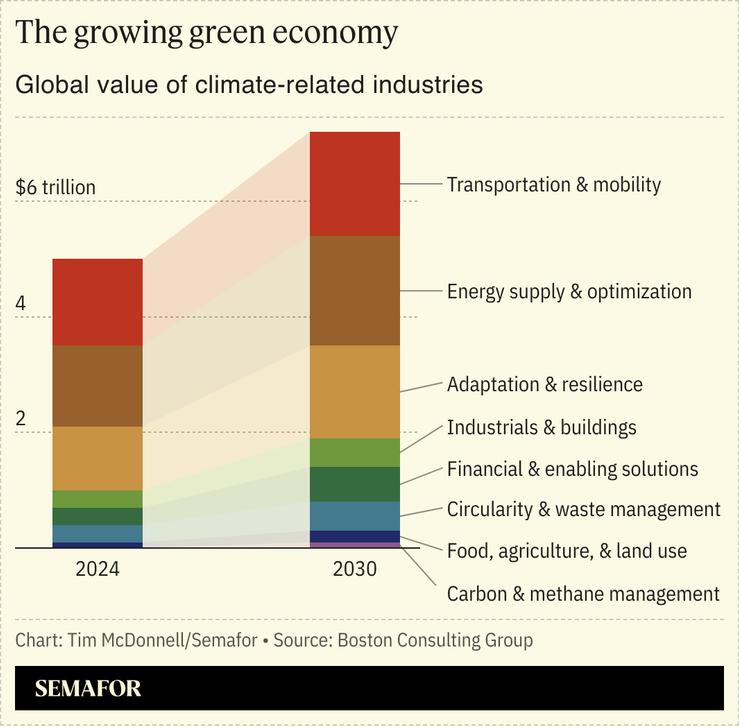

Businesses aimed at reducing emissions and adapting to climate change impacts are the second-fastest growing sector of the global economy after tech, and are on track to be valued at more than $7 trillion by 2030, a Boston Consulting Group study found.

Steeply falling costs for renewables, electric mobility, and other key technologies have made sustainability-related investments increasingly insulated from shifting political winds; more than half of global emissions can now be addressed using technologies that are already cost-competitive, the study found. And as climate impacts worsen, the potential costs companies face through inaction are mounting.

Whereas in the past many CEOs of large companies argued that sustainability-related investments were mainly a PR exercise, there’s a rapidly growing sense that “this is not about sacrificing the business, it’s about taking advantage of a growing part of the world economy,” Rich Lesser, BCG’s global chairman, told Semafor. The sustainability economy can be compared to AI, Lesser said: People might quibble about the pace at which it will progress, but “there’s no sense this trend will reverse. This is a long-term trend that is reasonable to bet on and probably risky to bet against.”

In this article:

Tim’s view

For many years the biggest obstacle to decarbonizing the global economy was the dreaded “green premium” that put environmental and financial sustainability at odds, and basically doomed the prospects for big companies to make long-term green investments without major government support, which was never very reliable. The green premium still exists for some technologies, like green hydrogen and carbon capture. But what the BCG report shows is growing proof of the opposite, what one might call the “brown” premium: Companies that don’t find a foothold in sustainability-related ventures risk missing out on major financial upside.

BCG’s analysis of revenue from more than 6,500 global companies between 2020 and 2024 showed that green revenue streams grew twice as fast as conventional ones. Overall growth tended to be higher in companies in which sustainability-related products or services made up a material part of the business: More than half of companies that saw compound growth rates above 30% earned at least 10% of their revenue from green enterprises in 2024. Companies with significant green revenue streams were also able to raise capital more cheaply, at an average discount of 43 basis points compared to companies without green revenue.

CEOs of companies that are successfully tapping into this growth tend to have a few things in common, Lesser said: They do everything possible to avoid green premiums by focusing on mature technologies and, where needed to eliminate lingering premiums, invest in economies of scale and R&D; they proactively engage with policymakers to shape relevant regulations and incentives in their favor; and they get creative about their funding sources, seeking out more diversified capital.

One other thing that many CEOs have in common these days on sustainability, Lesser said, is not talking about it publicly. Financial advantages aside, there is still a risk, in the US at least, of becoming a target by touting the emissions benefits of sustainability investments. “Green-hushing is real,” Lesser said. “Companies are reluctant to say things that could be interpreted as taking a political stand at a time when they just want to focus on business.”

Room for Disagreement

The exact extent to which the future global economy will be hurt by climate impacts is being freshly debated by climate economists, after the retraction this week of a high-profile study that had warned of particularly dire impacts and had been cited by numerous central banks as a justification for more stringent capital regulations. The study was retracted by the prestigious journal Nature after it was found to have major flaws in some of its data. But its authors have stood by their basic conclusion that climate change is a serious threat to global GDP.

Notable

- Private capital funds are increasingly exposed to major losses from extreme weather, the ratings firm MSCI warned. In a world with 3ºC of global warming, “the share of assets exposed to catastrophic losses exceeding 20% of their value is projected to increase five-fold — signaling a sharp escalation of tail risk.”