The Scoop

Prelude Capital — which invests about $9 billion across dozens of different asset managers — is marketing a new fund to potential investors.

The best part of the pitch: They don’t tell you about their recent losses, mainly from poorly timed bets on private Chinese bonds.

That’s because those losses aren’t “relevant” to the new equity-only fund, according to a person close to the pitch. The new fund would not include investments like the Chinese bonds and other credit plays, so the firm did not think it needed to disclose them in their pitch.

But in fact, Prelude’s massaging of numbers to raise new capital is increasingly typical in an industry more involved in the private markets than ever before. Hedge funds, venture capitalists, and private equity giants all tweak figures when it suits them.

The explosion in private market investing from the likes of Tiger Global and Fidelity during the 2010s bull run has critics waiting for big markdowns in the face of rising interest rates and falling valuations. But the companies have free rein to determine the value of these stakes themselves. Paper gains can be used to raise billions more.

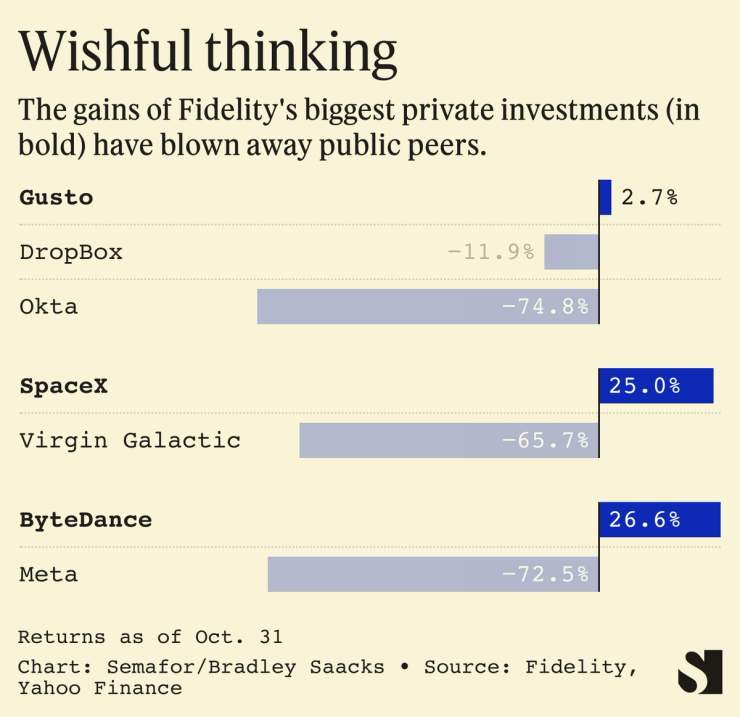

These valuations can be hard to explain. Fidelity, for example, increased the value of its stake in HR software unicorn Gusto, previously known as ZenPayroll, by 2.7% this year even though public peers like Dropbox and Okta have shed billions in market cap. The firm declined to comment on individual security valuations.

Tiger Global has marked down its private bets by 24% this year (but not before it raised $12.7 billion in March) — a significant drop, but this pales in comparison to the 50% loss in the Thomson Reuters Venture Capital Index or Nasdaq-100 Technology Sector Index’s 35% drop.

The financial giant Blackstone reported that its private credit book was up 9.3% for the year, while its liquid credit counterpart was down 4.6%.

Bradley’s view

It’s not lying and it’s legal, but it’s certainly not telling the whole truth.

Prelude wants to raise more capital, which is no small feat in the current environment. And as much as institutions and consultants say they do an extensive analysis beyond just the numbers, it’s hard to get in the door if the track record isn’t stellar.

There are too many asset managers chasing a finite pool of money, so allocators can be choosy and don’t need to take a risk on someone with less-than-stellar numbers. Past performance doesn’t guarantee future returns, but it does provide plausible deniability for the pension manager betting with teachers’ retirement money.

For Prelude, it’s a chicken-or-egg question. Were investors interested in a particular product and the cherry-picked track record was shown as an example of what Prelude could do in that context? Or did the manager want to raise money, and then created a product that would show off the best parts of their existing performance? My sources say the latter, though a person close to the firm said the new fund is “responsive to interest” from possible investors.

Room for Disagreement

Massaging numbers to put your best foot forward has gone on as long as there’s been an asset management industry. If you’re an alternative asset manager and want to do this without annoying consultants digging into the numbers, ask for a longer lock-up period.

Hedge funds like Millennium and Citadel, despite investing a majority of their capital in liquid markets, demand long lock-up periods from their investors in part to protect them from themselves. Look at how the private equity industry has used the relative permanence of its capital to grow itself.

Private equity platforms are now institutions because they churn out returns of 10% annually, so they claim. In reality the valuations of their holdings rise and fall against the market. It’s just that no investor feels that volatility because they can’t pull out and realize those losses.

When everything is on paper and investors aren’t able to redeem, track records are more wishful thinking then rock-solid numbers — a great asset for any business development team to have to raise money.

The View From Charlottesville

The CFA Institute has tried to tackle the cherry-picking problem with its Global Investment Performance Standards (GIPS), a 146-page guide that was updated in the summer of 2020. The goal is for investors around the world to be able to trust a track record from any firm certified by the institute.

The non-profit isn’t a regulator, so funds that don’t comply are not punished in any way beyond losing their certification from the institute. Still, the GIPS team at the Charlottesville, Virginia-based institute say 24 of the top 25 asset managers in the world comply with the standards, a part of the more than 1,700 managers and allocators that have signed on.

Notable

- The Financial Times’ deep dive on the “phoney happiness” of private equity surely made AQR founder Cliff Asness — who has written plenty about “volatility laundering” — smile.