The most frustrating statistic in African geoeconomics is the claim that the continent has 30% of the world’s mineral reserves. Similar thinking is driving both US-Africa policy strategists in the White House and pro-Africa analysts on the continent keen to improve its geopolitical standing.

The earliest record I could find of this data-hollow framing was from a 2002 African Development Bank paper, and I have been warning against it for more than a decade. Yet, respectable international organizations like the World Bank still push this flawed narrative.

Africa’s share of global “critical minerals” production and reserves is actually less than 5%. Some, in trying to explain Trump’s renewed Africa interest, have specifically claimed African countries are rich in rare earth minerals, but again, that’s just not true. Only two African countries — Madagascar and Nigeria — produce any significant quantity of rare earths, and together, they make up barely 4% of the global total.

You might ask if it really matters. What’s wrong with a bit of hype? A lot, in my view.

Mischaracterization results in bad strategy and poor policy by distorting what’s important. For example, rare earths as a category is a low-sized economic affair — projected at approximately $8 billion by 2032. That is less than half what Ghana alone earns from gold nowadays. Mischaracterization also lures African policymakers and business leaders into looking at “critical minerals” at a global vantage point beyond Africa’s economic capabilities instead of from the continent’s specific, challenging context.

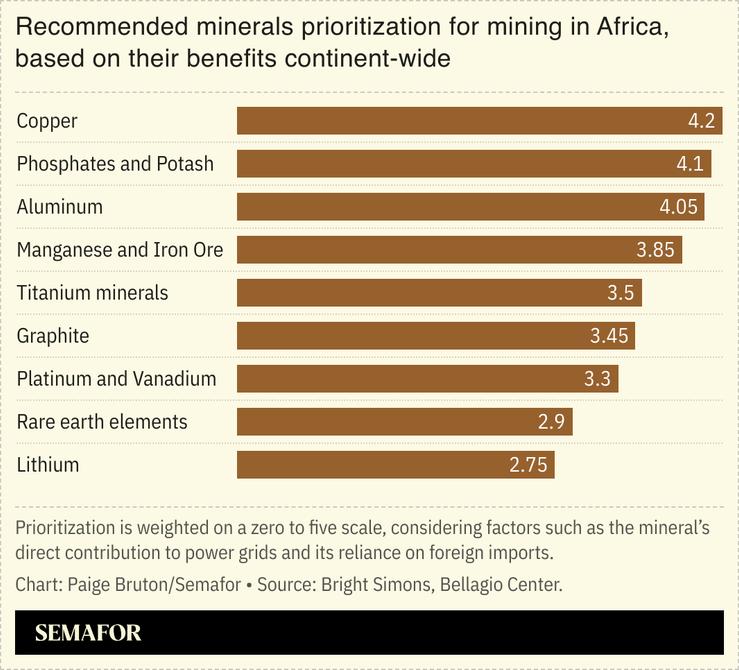

But there is a more effective way to position the collective potential of the mining industries in African countries if we consider the African Union’s three main strategic mining blueprints on a common vision for the continent, on green minerals specifically, and on governance. I took key ideas from these papers to develop a framework for what mining can achieve in Africa, based on which I synthesized the Strategic Transformation through Resilient Industrialization and Value Enhancement (STRIVE) list. It redirects us from definitions typically used by technocrats in the US, EU, and Japan, and identifies a set of minerals most critical for realizing that composite vision for Africa.

The list favors bulk-industrial minerals. When Europe was industrializing during the 19th century it was a world-leading producer of the minerals most critical for its modernization such as iron and coal. Hence why the EU first emerged as a steel and coal club.

Africa today is, for the most part, deficient in copper (from a reserves standpoint), potash, and most steel-making minerals. Should Africa’s current industrial output double, most African countries would become major net importers of various critical minerals. Only a truly workable regional integration strategy would save the day.

But that requires interstate digital public infrastructure, the one thing we haven’t tried. A digital public infrastructure platform for mining in Africa would bring much-needed visibility and analytical clarity to the urgent task of creating regional value chains for STRIVE (industrial) minerals to benefit the majority of African countries, which are mineral-poor.

But why would countries bother if they are deluded into thinking that Africa is awash with minerals?

Bright Simons is an honorary vice president at IMANI, an Accra-based think tank, and a visiting senior fellow at ODI Global in London.