The Scene

This story is excerpted from The Fund: Ray Dalio, Bridgewater Associates, and the Unraveling of a Wall Street Legend, by Rob Copeland.

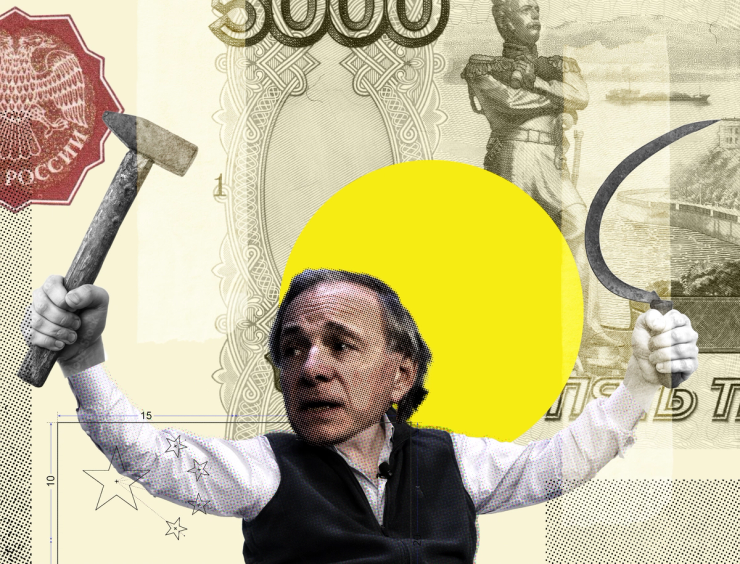

In a posh New York apartment, Lee Kuan Yew was discussing global affairs when his dinner companion asked the former Singaporean prime minister whose governing model he most admired. Lee gave an unlikely answer: Vladimir Putin, who had stabilized Russia after the chaotic collapse of the Soviet Union.

To Ray Dalio, sitting across the table, the analogy would have been seamless. The CEO of Bridgewater Associates, the world’s biggest hedge fund, had stabilized it in 2015 after a tumultuous stretch of bad press, putrid investment performance, and persistent executive turnover.

Dalio, famed for his so-called Principles, or rules for life and work, turned his attention, bordering on obsessive, to meeting Putin. He asked Bridgewater’s client-service team to call in favors abroad to gain him an introduction. This proved more difficult than expected. Putin was not known for giving audiences to American businessmen — even those as famous as the Bridgewater founder. Through intermediaries, Dalio said he was happy to audition.

He invited one of Putin’s closest allies, Herman Gref, to visit Bridgewater headquarters. Gref, who was chief executive of the state-run Sberbank, arrived in the spring of 2015 with a small entourage. He was whisked in to see Dalio, who showed off the hedge fund’s employee rating tools, called Principles Operating System, or PriOS. Everything at Bridgewater, he explained, operated off a strict set of rules: how it invested its billions, and how it promoted and fired its employees.

Dalio offered to set up a similar system for the Russians. Gref expressed intrigue and suggested that he might be able to introduce Dalio to Putin at the Russian leader’s palace in the resort town of Sochi.

Dalio could scarcely contain his excitement in the days that followed. Yet every time he asked his team for an update, he learned that the Putin meetup had been postponed once again. Spurned, the Bridgewater founder turned his gaze farther east, to another foreign power ruled by a strongman.

Dalio had been fascinated with China for decades, long before the growing nation became a mainstream destination for Western businesspeople. In China, he found the perfect confluence of his interests: a collectivist society that demanded its citizens defer their short-term interests and gratifications for those of the state and its rules, for the promise of a long-term reward. As Dalio would say in a 2019 video taped with a Bridgewater staffer, “Curiosity brought me in contact with the Chinese people, who I really, really came to love and admire [for] the character of them, and what type of relationships that they valued.”

Dalio first visited China in 1984 with a small coterie including his wife. For a Harvard Business School graduate who had married into staggering familial wealth, the experience was eye-opening. The group met with representatives of CITIC, a giant government-run conglomerate that would later boast operations in real estate, banking, metals, and a slew of other industries.

The Bridgewater founder made inroads in a society with a strong distrust of outsiders. He sent his 11-year-old son to live with a local family in Beijing and later staked a charity, which built orphanages for disabled Chinese children. Dalio also ramped up his efforts to raise money for Bridgewater from the country’s deep-pocketed but closed-off government institutions.

Seizing on nationalist concerns and mistrust between the two nations, he said in one meeting: “Whatever fees you pay, I will donate back to China personally.” Bridgewater collected more than $10 billion for its funds from Chinese government wings and Dalio gained entry into a rarefied world. He became close with Wang Qishan, later China’s vice premier and then the head of the Communist Party’s anti-corruption arm.

Wang had instincts that wouldn’t be out of place at Bridgewater; at one meeting of his own deputy investigators, he surprised the group with dossiers of their own transgressions. Wang’s apparent aim “was to terrorize the enforcers themselves,” the Economist reported, adding that “Failure to uncover high-level graft . . . would be ‘dereliction of duty.’” The publication called Wang perhaps the most feared man in China. Dalio called him a friend, a hero, and “a remarkable force for good.”

The two men met for at least an hour on each of Dalio’s trips to China, chatting about philosophy and the world order. Wang returned the favor by endorsing one of Dalio’s most prized Principles: “Pain plus reflection equals progress.” “If conflicts got resolved before they became acute, there wouldn’t be any heroes,” Wang told Dalio during one visit.

Through Wang, Dalio learned about the complicated machinations of the Chinese governing system. The country was expanding a so-called social credit system, in which the government attempted to track the personal behavior of each citizen, down to infractions as small as jaywalking, and used the data to calculate an omnibus personal rating that determined whether someone could receive a loan, a job, or other benefits. The goal was, as the Chinese government put it, to create a “culture of sincerity.”

Dalio must not have been able to help but see the connection to the radical truth and transparency system he had implemented at Bridgewater, as well as his mushrooming system of ratings tools and software that divvied up employees based on their personalities and purported abilities.

The Chinese government, like Bridgewater, was organized as a set of committees with overlapping members, all reporting to President Xi Jinping, who periodically ordered his underlings at the Politburo to engage in “self-criticism” to reaffirm their loyalty to him. There were just seven members of the Politburo Standing Committee, and Dalio’s friend Wang was one of them.

In 2015, inspired by the Chinese system, Dalio sought to re-create parts of it in Connecticut. Without telling clients or the public, he put out a call inside Bridgewater for young staffers who wanted to help reshape the firm in accordance with The Principles, a plum gig sure to provide a chance to impress Dalio. Those who stepped forward were assigned to a dizzying array of new enforcement bodies, with rather unsubtle names.

The Principles Captains, those assessed to be the most knowledgeable about Dalio’s manifesto, fanned out across the firm to assess whether individuals were acting in accordance with how Dalio himself might have acted. The Auditors monitored department heads. The Overseers had no easily definable responsibilities, save for reporting to Dalio on the goings-on of the other new groups. “The worst thing,” said one employee, “is for an Overseer to find a problem before I find it.”

The crown jewel of Dalio’s new creations was called the Politburo. The roughly two dozen members were mostly in their twenties or thirties. They were handpicked by Dalio and given vast remits to conduct investigations across the firm. Members would barge uninvited into meetings — or listen to recordings afterward; everything at Bridgewater was recorded and had been for decades — and rate their colleagues. The members caught, and squelched, dissent before it reached Dalio’s desk. It was a dream come true. Now the Bridgewater founder had eyes and ears everywhere.

Finally around 2018, Dalio’s efforts to meet Putin paid off. Word leaked inside Bridgewater that Dalio had gone to visit the Russian leader. Even some in the firm’s top ranks weren’t sure if it was true, and Dalio wouldn’t answer to underlings when questioned directly on the subject. For Karen Karniol-Tambour, the cohead of investment research and known internally for deftly playing the game of agreeing with Dalio, it was too much.

Rising from her seat at a Bridgewater town hall, shaking with nerves and voice rising, to assail Dalio about Putin. “How do you deal with this war criminal?”

Don’t be so simpleminded, Dalio replied. He told her to keep her emotions in check, as The Principles prescribed. “If you’re so smart,” he sniffed, “why aren’t you rich?” It was a line Dalio had used countless times before.

Dalio’s put-down seemed to strike a nerve inside Karniol-Tambour. She tore into him, saying that she would not sit idly by while a powerful man ran roughshod — not if the man was Ray Dalio and not if it was “Hitler.” There were gasps at the comparison.

Word reached the Bridgewater executive ranks that Karniol-Tambour was turning into something of a sympathetic figure inside the firm — and that Dalio was coming off as the villain. Dalio’s solution: A private conversation with Karniol-Tambour.

Afterward, he sent out an email to a wide group at the firm that read, in part, “I’ve spoken to Karen and she’s fine, and she asked me to continue doing what I’m doing with her.”

Karniol-Tambour responded that she was grateful to have the opportunity to continue to learn from Dalio. She was not long after promoted to co-chief investment officer for sustainability, a lofty title for a role that hadn’t previously existed, and set up by Bridgewater’s public relations team for splashy magazine profiles on her investment prowess.

Once again, Dalio had wriggled his way out of a jam.

The View From Ray Dalio

“Bridgewater obviously is not and was not as he describes it,” Dalio said in a statement on the book. “If it were, it wouldn’t have had so many happy employees who have stayed so long (about one-third have been there for over 10 years) and it wouldn’t have such great client loyalty and longevity (the average client has been with Bridgewater for 12 years). So this book is more a sign of the times when bad journalism is more a fiction than a source of truth.”