Q&A

Up until now, Chicago Federal Reserve President Austan Goolsbee has been more worried about a weakening jobs market than inflation. The government shutdown has changed his thinking.

Goolsbee said in an interview that the lack of recent inflation data leaves the Fed with “one eye covered.” There are alternative sources for jobs data, such as ADP’s private-sector payrolls and proxies produced by the Chicago Fed, which Goolsbee oversees, but few good ways to track consumer prices.

“Being in the dark on half of the mandate leans me toward being extra careful because we’re not going to see if the inflation side starts going wrong,” he said. “If you look out the window and the last thing you saw was a mountain lion in your front yard, before you open the door and send the puppy out, get another view!”

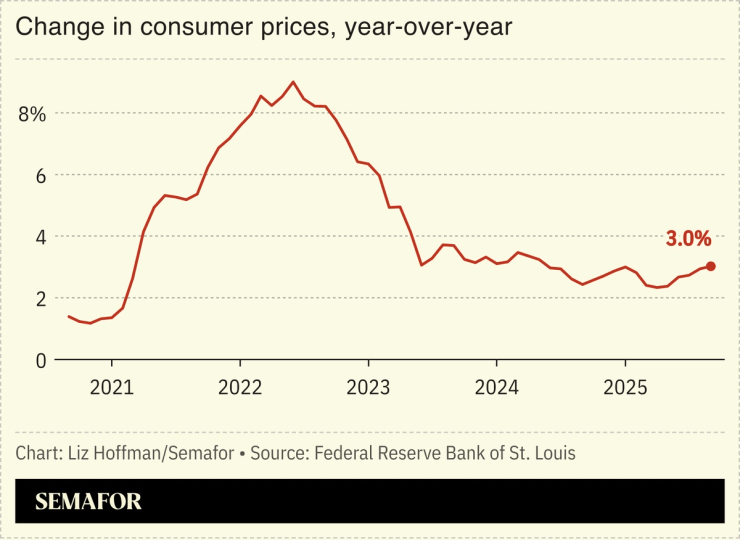

That second view won’t come until the shutdown ends and the government starts releasing inflation data again. Inflation has ticked up steadily since the late spring and is higher than the Fed’s 2% target. Tariffs can’t explain sticky inflation in services. (Hotel stays aren’t imported.) And businesses that have so far swallowed the tariffs without raising prices may not be able to for much longer.

Goolsbee said he’s undecided about whether to back another interest rate cut next month. He voted in favor of the quarter-percentage point cut the Fed announced last week, at a fractious meeting that saw two members of the rate-setting committee dissent in opposite directions — something that’s happened only one other time since 2013.

“I still believe that rates can come down a fair amount,” he said, but he worries about “front-loading” cuts without more data. The US economy is “basically strong and stable… I just want to be sure that inflation is transitory.”

That word has gotten the Fed into trouble before. Consensus that post-pandemic inflation would pass as supply chains unkinked and people blew off steam and savings proved to be wrong, a mistake that undermined public confidence and at least partly opened the door to political pressure from President Donald Trump.

This interview has been edited for clarity and condensed.

Liz Hoffman: What’s your read of the balance right now between inflation and jobs, and where we ought to be most concerned?

Austan Goolsbee: Core inflation is running at 3.6% annualized rate and core services inflation is close to 4% for the last three months. In an environment like that, I want to have clarity that this is a transitory inflation shock. The fact that it’s having an impact outside of just the tariff lane is a little unnerving.

And we’ve got one eye covered. We can still see things happening in the labor market. If the labor market deteriorates, we’re going to see that in unemployment claims and the Chicago Fed labor market indicators, we’re going to get observations from ADP. If it starts deteriorating on the inflation side, we’re not going to see it while the government is shut down. Being in the dark on half of the mandate leans me toward being extra careful, because we’re not going to see if the inflation side starts going wrong. I still believe that rates can come down a fair amount. I just want to be sure that inflation is transitory.

When the [government] data are turned back on, we should get a pretty quick sense of whether tariff-driven inflation has already peaked and is coming down, and whether this uptick in services inflation proves to be a blip.

It sounds like you’re saying the shutdown is having a real impact on how you’re thinking about the balance of the risks.

It is. If you have information on one side of the mandate and not the other, then it automatically generates more caution on the side that you cannot see. If you look out the window and the last thing you saw was a mountain lion in your front yard, before you open the door and send the puppy out, get another view! The last three months of inflation weren’t terrible, but they were not heartening. We’ve been above the target for four-and-a-half years, and [for] the last three months, trending the wrong way. I do have uneasiness with front-loading rate cuts without information.

Where are you right now on another rate cut in December?

I’m still undecided. I do think rates can come down, but they should be coming down with inflation. In 2024, inflation was coming down and we still waited a significant amount of time before we began cutting rates, until we were sure. I’m uneasy with front-loading the rate cuts and counting on the inflation to be transitory. Given our recent history, that seems like a risky thing to do.

What is the labor market telling us right now?

It’s mostly been steady. The deterioration in the labor market has been concentrated in payroll employment, which is the [datapoint] that is the most susceptible to demographic and immigration changes. So we want to be careful overindexing on that.

I’m looking more at what I call the four horsemen of truth. These are things that proved better indicators of where we were in the business cycle in 2023 and 2024: the unemployment rate, the hiring rate, the layoff rate, the vacancy rate. Now, the government is shut down, so there are no official statistics, but for three of those four, we can still get an estimate. And the level is pretty good in most of them. It’s a low-hiring, low-firing environment. That’s unusual, but not really a sign of the business cycle turning.

What’s it a sign of?

To me, it likely reflects a high-uncertainty environment. If this is about uncertainty, my hope is that it is going to get resolved in the near term. And when I’m out in the district talking to business leaders, they don’t know where things are going. They’re not getting rid of their people, but they’re not hiring new people. They want to see how things are going to play out before they make these decisions. But this could be the start of a period of stagflationary shocks where both sides of the mandate get worse at the same time. That’s a much more difficult circumstance for the central bank to be in, because it’s not obvious how to respond.

Does that explain the fraying consensus we’ve been seeing inside the FOMC?

I won’t speak about what’s in anybody else’s head. But as I outlined a year ago, if we got big tariffs that were a stagflationary shock, or if we got some other stagflationary shock, the Fed would be in a difficult situation. Because there’s not an obvious playbook of how you deal with both sides getting worse at the same time.

I think the economy is basically strong and stable. The unemployment rate is low and there are weaknesses, we’re never in paradise, but I think it’s basically a pretty strong, stable economy where the main power driver has been consumer spending, and that’s contributed to strong, robust GDP growth. If we can get the dirt out of the air, especially on inflation, my belief is that a year from now, rates could be a fair bit lower than where they are today.

Are you worried about an AI bubble?

I am nervous about that. It’s always hard to tell whether something’s a bubble when you’re in it, but there’s certainly warning indicators, with credit spreads being as tight as they’ve ever been and valuations being as high as they are. What that means for monetary policy, to me, is just another cautionary note: If it turns out that’s a bubble, cutting rates into the face of a bubble is a little bit of a dicey proposition, and cutting rates into the face of rising core inflation is a very unusual circumstance.

It’s not obvious that monetary policy can pop a bubble. I think there’s a lot of evidence that it can fuel a bubble.

Where are you on the cockroaches vs. canaries discourse right now, looking at some of these recent bankruptcies in riskier corners of the credit market?

I have an eye on it. It goes to the — is it a conundrum? There are some bankruptcies, yet credit spreads on risky bonds are as small as they’ve ever been. So you’ve got some things saying risk is up, but others saying the market believes risk is very low.

The last time you and I talked, the political pressure on the Fed was very front and center. It’s been quieter lately. Are you heartened by that? There’s obviously a process right now to find a replacement for Chair [Jerome] Powell.

Central bank independence from political interference when setting rates is critically important. And my experience in nearly three years at the Fed is that everybody sitting around the table takes the job extremely seriously. People base the rate decisions on economic conditions and economic outlook. I have a lot of confidence in my colleagues, and in the FOMC.

Economic growth isn’t explicitly part of the Fed’s mandate, but how are you thinking about how AI is going to impact economic growth and employment?

If productivity growth is going to be that high, then incomes are going to start growing even faster. That solves a lot of problems, a lot of ills of society.

Do you worry about extreme jobless growth, where we’re all really rich but the robots have taken all the jobs?

I think job displacement by technology is a short-run phenomenon. We’ve got 150 years or more of jobs being specific job tasks being displaced by technology, and the unemployment rate is still 4.3%, not 100%. In the short run, that can put a pinch on job growth. In the longer run, I think there’s not really a tradeoff.

Notable

- On the heels of major tech sector layoffs, Reuters’ Jamie McGeever argues the US economy is in fact closer to “no hire, more fire” than “low-hire, low-fire.”