The News

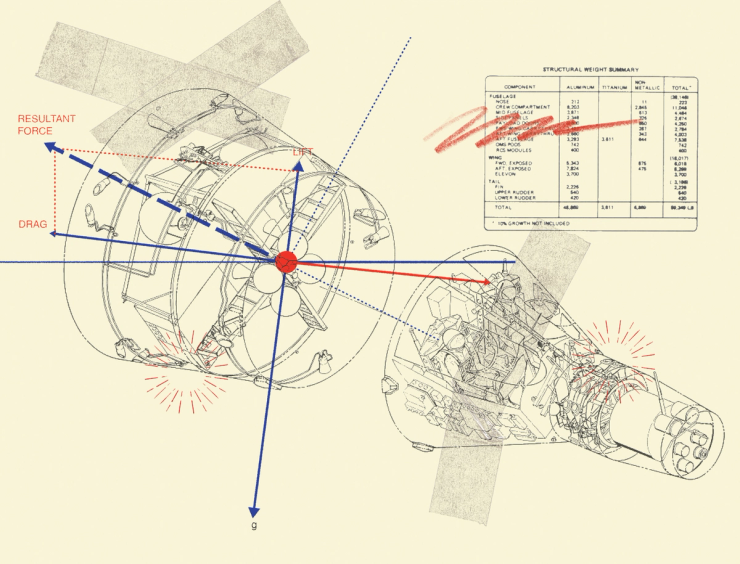

Francisco Cabada was conducting a routine pressure valve test on SpaceX’s raptor engine in the afternoon of January 18 when something went wrong.

Cabada, a ten-year veteran at the company, shouldn’t have been near the valve when it hit maximum pressure, according to people with knowledge of the accident, but it ramped up faster than expected, blowing a shield off the valve and knocking him unconscious. The injuries were extensive, affecting his head, upper and lower extremities and his respiratory system, according to California’s Department of Industrial Relations.

Cabada, a father of three from South Central Los Angeles, was taken to a hospital to be treated for a skull fracture and head trauma, according to the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. He remained in a coma for months.

SpaceX was fined $18,475 by OSHA for two safety violations, one of which was rated the highest penalty level of “serious” and a maximum gravity of 10. The OSHA case is still open.

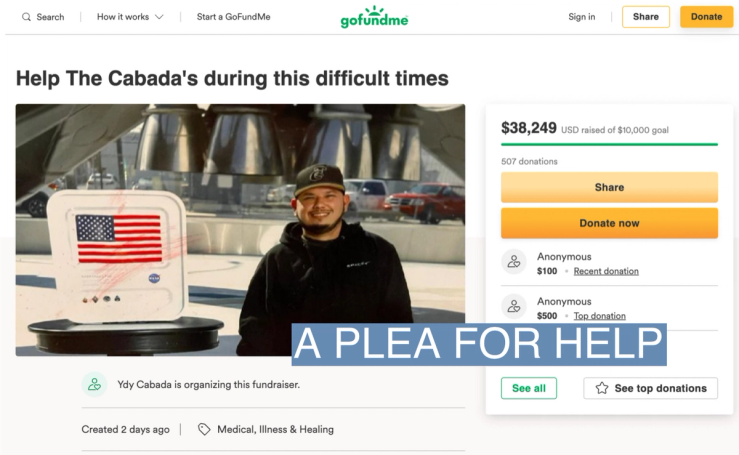

SpaceX has made no announcement to the public or to its workers about his status, according to former employees who were shaken by the accident. A half dozen former employees said they were concerned Cabada’s family would not be properly compensated if he can no longer work, or worse. Hundreds of his co-workers donated to Cabada’s Go Fund Me page, which raised more than $51,000.

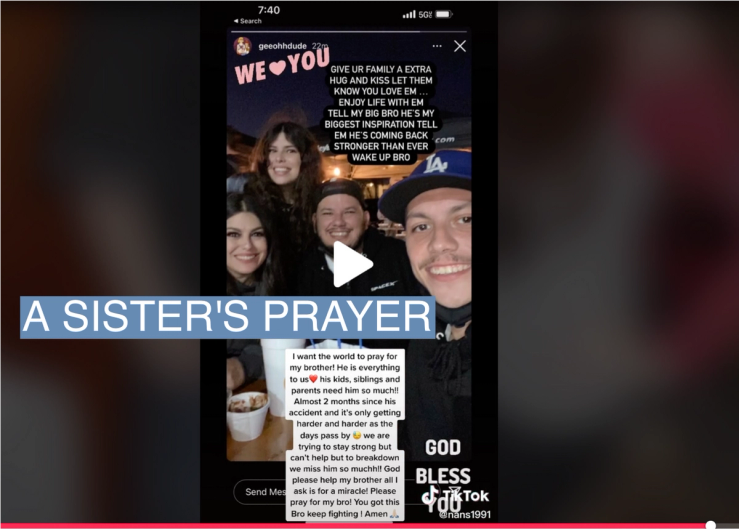

In a TikTok video, Cabada’s sister called him her inspiration. In a photo slideshow, Cabada is shown with his family, dressing as Santa, donning a Los Angeles Rams jersey and wearing Aguacateros de Michoacan gear - a Mexican basketball team. “Tell ’em he’s coming back stronger than ever. Wake up bro,” his sister wrote.

Cabada is out of the coma but has not been able to communicate and can’t survive without medical assistance, according an attorney for the family and his brother-in-law. It’s unclear whether he will ever be able to leave the hospital.

In this article:

Reed’s view

The company’s silence on the incident is a particularly dramatic reflection of a core dynamic in America’s new space race: The unspoken truth that human lives are at play at every level. That’s true for high-flying astronauts, and for billionaires who dream of dying on Mars. But it’s truest of all on the ground, where an obscure, tight-knit community of technicians have the job of taking some of the world’s most flammable substances and making them burn at the highest pressure possible.

“We have flammable liquids on site in bulk quantities. We’ve got cryogenics, high pressure gasses, inert gasses that can create oxygen deficient atmospheres. Those commodities are very dangerous,” said Preston Wood, senior manager of environment, health and safety at Relativity Space, a SpaceX rival. Relativity has a strong safety record relative to others in the industry, with just one OSHA safety inspection since it was founded in 2015. The inspection, spurred by an accident, did not result in a violation.

Like astronauts, technicians know they are taking a risk working in an industry aimed at creating the most powerful controlled explosion possible. Three died building the first manned space vehicle for Virgin Galactic, the Space Ship Two, in 2007, when a nitrous oxide tank exploded during one of the tests.

Yet their names—Eric Blackwell, Todd Ivens and Charles “Glenn” May—are not on the Space Mirror Memorial in Cape Canaveral. Only those who flew or trained to fly on rockets are given that honor.

Since 1980, at least 24 workers (mainly technicians) have been killed while at work in the space industry while many more have sustained injuries that were never reported or are not classified as space industry accidents in the data.

The technicians are the unsung heroes in the space industry. Their training, real-world experience and knowledge of the engines allow private space companies to test and iterate faster.

“They’re by far the most knowledgeable people about what the engine should look like,” said Andy Guymon, a former NASA engineer who is now a senior propulsion engineer at Relativity Space. “We lean on them a lot.”

Space Race

The private space industry is booming, thanks to companies like SpaceX, Virgin Galactic, Blue Origin and newcomer Relativity Space. These ventures have expanded the capabilities of rockets by borrowing a technique that’s usually associated with software companies like Facebook: They embrace failure as a method for rapid improvement, an approach that software companies like Facebook like to call, metaphorically, “move fast and break things.“In the hard tech of the space industry, that’s not a metaphor.

“A high production rate cures many ills,” SpaceX founder Elon Musk, said in a July interview. “Any given technology development is how many iterations do you have and what’s your time and progress between iterations. You can try lots of different things and it’s ok if you blow up an engine because you have a high production rate.”

With that philosophy, Musk and SpaceX have pushed costs of space travel down dramatically, setting off a new space race between private companies. According to a May report from Citibank and McKinsey, the cost of sending a rocket into space ranged from $16,000 to $30,000 per kilogram. SpaceX’s Falcon 9 reduced the cost to $2,500, according to the report, which predicts the rapid pace of innovation will bring costs down to $100 per kilogram by 2040.

That iterative approach means more testing. And that means more work for the technicians who must ready equipment each time engineers fire up a rocket to determine the success of a newfangled design.

In the accident involving Cabada, OSHA’s accident investigation summary noted that “the final step in the pressure check operation, venting, was done for the first time using an automated program as opposed to the normal manual method that had been used in previous operations.”

Test Day

I saw the importance of workers like Cabada first hand one recent morning at the Stennis Space Center in Mississippi. Chris Ledoux’s “This Cowboy’s Hat” blared on the massive test stand as Relativity engineers were getting ready to fire up the second engine, a new design known as “Delta Qual,” when apprentice technician Jen Peterson discovered something perplexing. Before each engine test, technicians are responsible for a final leak check. Engineers squirt a yellowish liquid (essentially soap and water) onto valves and lines and look for air bubbles, an indicator of a leak.

“Hey Robert, you ever seen this shit before?” Peterson asked. Robert Caldwell, a military veteran who has worked on fighter jets and Apache helicopters, walked over to the engine stand to observe. Small bubbles appeared on the surface of the gas generator, a key component that acts like a mini rocket, powering other parts of the engine.

Peterson used a tiny video camera attached to a cable to search inside the gas generator for the source of the leak. She soon found it: A practically microscopic hole that, on the video screen, looked like a gray smudge.

Without her catch, the part could have failed during a high pressure test.

At 8:30 p.m., nearly 15 hours after the technicians showed up for work that day, sirens blared, the perimeter was cleared, and a countdown began. A blue flame ignited and a bone-rattling roar consumed the pitch-black swampland for a long five minutes.The technicians showed no signs of exhaustion. “We’re testing rockets, baby!” Caldwell said.

Cabada also loved his job, according to former colleagues. And none of the more than a dozen space industry technicians I spoke to for this story advocated slowing down. Advances like reusable rockets that fall back to earth and land themselves at SpaceX and elsewhere wouldn’t have happened for decades, if ever, without some risk-taking.

The Go Fund Me page for Cabada, which appears to have been set up by his sister-in-law, initially included a photo of Cabada wearing a SpaceX sweatshirt, grinning in front of a rocket that sits in front of SpaceX’s Hawthorne headquarters. As the family’s legal talks with SpaceX began, it was replaced with a picture of him at a restaurant.

The attorney for the Cabadas said the cause of the accident is being investigated as part of the worker’s compensation case.

Room for Disagreement

There’s a long American tradition of doubting whether getting to space is worth the costs. Civil rights leaders protested spending public money to get to the moon instead of relieving poverty, a sentiment captured in the Gil Scott Heron poem “Whitey on the Moon.”

Today speed and competitive pressure in the private space race make workplaces necessarily unsafe, and even some inside the industry have raised questions about it. In an open letter to the management of Blue Origin, the rocket company owned by Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, a group of 21 employees signed on to criticize the company for prioritizing speed over safety, despite company promises that Blue Origin had built “the safest space vehicle ever.”

“At Blue Origin, a common question during high-level meetings was, ‘When will Elon or Branson fly?’ Competing with other billionaires—and ‘making progress for Jeff’—seemed to take precedence over safety concerns that would have slowed down the schedule,” the employees wrote.

The View From China

In China, getting to space is about more than lowering costs and creating new industries - it’s about winning the technology cold war with the U.S.

China has traded some of its citizens’ lives for speed, and paid with major accidents like the 1996 Intelsat disaster in which a Chinese rocket veered off course and struck a nearby village.