The Scene

Of all the battlegrounds in Washington’s technology war with Beijing, the Great Rift Valley may be the most beautiful. Rolling green hills stretch for miles against the backdrop of a bright blue sky, punctuated only by white clouds hovering over the highest peaks. Groups of monkeys amble by the side of dusty brown roads, while eagles glide overhead.

The tectonic shifts that carved out this lush vista 30 million years ago mean much of this land sits atop pressurized steam, groundwater, and hot rocks — a geological bounty that Kenya has tapped to become the world’s sixth-largest geothermal energy producer. A site here — in the Olkaria region, around 60 miles (100 kilometers) from Nairobi — was earmarked last year for a $1 billion geothermal-powered data center in a deal announced by UAE AI firm G42 and Microsoft.

Olkaria represented a one-two punch for a modern data center: untouched land to build, and clean, cheap energy to power it. When they announced the project, its backers said the first phase of the project was expected to be operational by around May 2026.

However, only months before that deadline, the effort is languishing. Developers have yet to break ground, while people familiar with the matter in the UAE, Nairobi, and Washington catalog problems with the project, extending from grand geopolitics to quotidian financial snags. On a recent visit to the Olkaria geothermal complex — five power plants dotted across hills and fields — officials from Kenya’s state-run energy company pointed to an untouched stretch of verdant land where the data center would be built. There wasn’t a construction worker in sight.

The project offered a blueprint through which US tech companies — alongside allies’ own AI firms — could help Washington loosen Beijing’s grip on digital infrastructure in Africa, and power American efforts to win a technological race with China.

Instead, it has fallen behind, sliding out of US political priorities and undone by the challenge of creating a financial logic for geopolitically driven deals in emerging market battlegrounds between the US and China.

Know More

When it announced the deal in May 2024, Microsoft said the roll out of cloud-computing in East Africa through the Olkaria data center would improve prospects for its Azure products in the region. As part of the agreement, the Kenyan government — which already provides digital access to public services through its eCitizen platform — planned to move more operations to the cloud. G42 was brought in as a key partner.

The problem: The companies have struggled to figure out what Microsoft’s cloud services will actually be used for, beyond Nairobi’s commitment. Two people with direct knowledge of the project said — 15 months after the deal was inked — G42, Microsoft, and the Kenyan government are still working on identifying the business rationale and a sustainable financial model.

“It all came together in a very geopolitical way,” one of the people, a tech infrastructure financier who was involved in talks about the project’s development and who spoke on condition of anonymity, told Semafor. “The UAE government was scrambling to give the US something to make up for their previous dalliances with Huawei.”

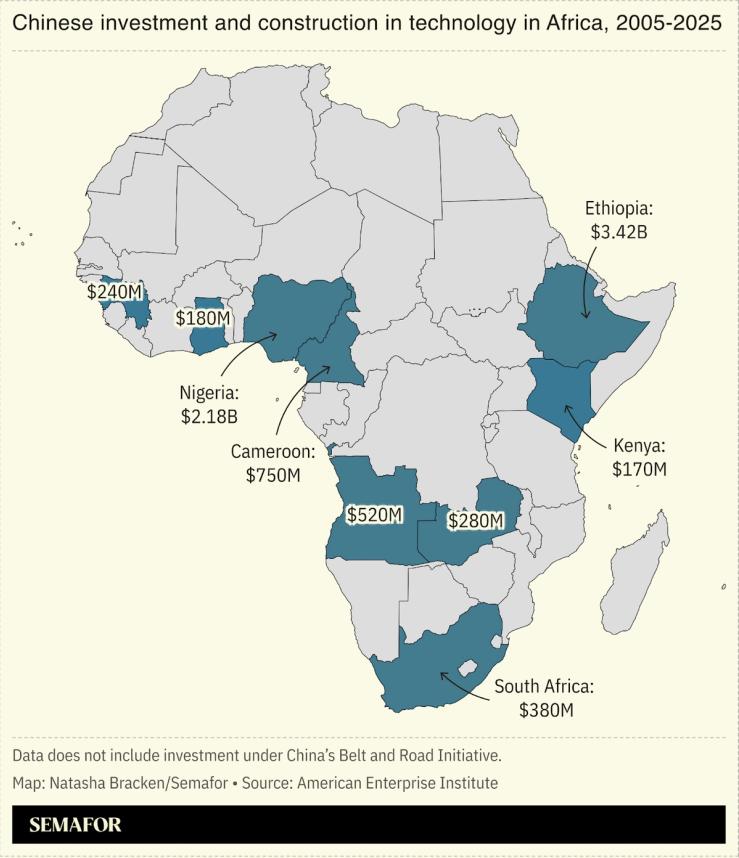

Through its tech giants, China has become a key player in Africa’s digital infrastructure development over the past decade: ZTE manufactures telecoms hardware and China Telecom is an internet access provider.

It is Huawei, however, that is most deeply embedded in Africa’s tech ecosystem, providing cloud, data center, and power grid modernization across the continent. The Shenzhen-headquartered company — the world’s biggest supplier of telecoms equipment — has built around 70% of Africa’s 4G networks, partnering with governments and companies in the continent’s largest economies, including Ethiopia, Kenya, Nigeria, and South Africa.

Huawei has established itself as an attractive partner for African nations by providing infrastructure at significantly lower prices than Western competitors, while working closely with governments to quickly deliver large-scale projects. Its investment in digital skills training has burnished its reputation across the continent as a company willing to provide long term partnership.

G42 also maintained ties with Huawei, which provided servers and data center networking equipment to the Abu Dhabi-backed AI conglomerate. But the Biden administration reportedly voiced concern over the relationship, and so, in late 2023, the Emirati firm announced that it was severing ties with Huawei to ensure access to US-made chips. “For better or worse, as a commercial company, we are in a position where we have to make a choice,” G42’s CEO Peng Xiao told the Financial Times. “We cannot work with both sides. We can’t.”

Ultimately, those efforts led Biden to approve cutting-edge chip exports to Abu Dhabi, Semafor has previously reported, and last year Microsoft invested $1.5 billion in G42.

Around the same time, years of behind-the-scenes work by then-US Ambassador to Nairobi Meg Whitman, to present Kenyan President William Ruto as Washington’s preferred business and political partner in Africa, were paying off. With her backing, Ruto secured an historic state visit to the US in May 2024 — the first by an African leader in 16 years.

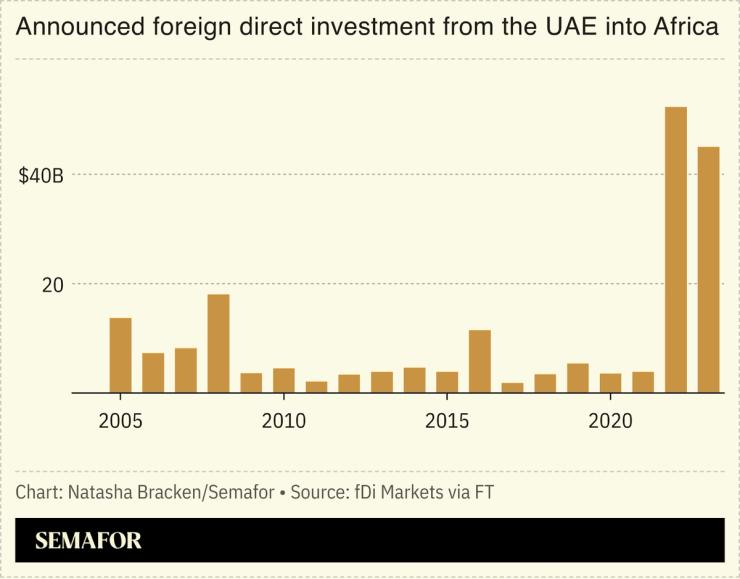

It was then that Microsoft and G42 announced their partnership to build a data center in Kenya, with financing led by the Emirati firm. It marked the latest step in a trend that has seen the UAE become among the largest foreign investors in Africa, having surpassed China in terms of total announced investments. And that it came during a state visit by the Kenyan leader made clear the underlying geopolitical nature of the deal.

Even at the time, officials acknowledged the deal was far from a typical business transaction. “This partnership is bigger than technology itself,” Ruto said. He called it a “coming together of three countries with a common vision.”

If the Olkaria project was forged by geopolitics, it has also been undone by geopolitics — at least in part.

In the months since US President Donald Trump took office, technology has, if anything, surged closer to the center of the political agenda, yet that has counterintuitively cemented the Kenya deal’s laggard status.

Artificial Intelligence has driven much of the conversation in the US, and prioritizing American dominance of the technology is a rare issue in which there has been bipartisan agreement in Washington: An AI action plan published by the Trump administration in July states that the US “must meet global demand for AI” by exporting relevant technology to other countries. It makes the case that American companies must look abroad in order to “stop our strategic rivals from making our allies dependent on foreign adversary technology.”

And in practice, Trump’s AI ambitions have shown themselves to far surpass the Olkaria project.

At home, his strategy encompasses the $500 billion Stargate joint venture with OpenAI, Oracle, and SoftBank that aims to build a network of data centers across the US.

Abroad, the focus has been on advanced economies which offer a safer bet than emerging markets such as Kenya. In May, Trump announced deals with the UAE worth $200 billion, which included plans for the Gulf state to build the largest AI campus outside the US. And last week Washington unveiled a $42 billion technology deal with Britain to boost ties in AI and quantum computing.

By comparison, Olkaria is large, but far from all-encompassing. Combined with Africa typically ranking low on Washington’s list of priorities, the project has not garnered much attention, overtaken by bigger targets in more prominent locations. A White House official, who spoke to Semafor on the condition of anonymity, said the administration’s focus has been on the Gulf and Europe. Africa isn’t on the radar and isn’t seen as an urgent battleground in the tech war with China.

Semafor sought comment from the White House over the Kenya data center project. In response, White House spokesperson Kush Desai said: “President Trump pledged to cement America’s dominance in cutting-edge technologies like AI and cryptocurrency, and the Administration is committed to delivering on this agenda at home and abroad.”

G42 did not respond to a request for comment on the project’s delay or a revised timeline. Microsoft declined to comment.

Alexis’s view

Olkaria should have been a slam dunk. The plan to tap geothermal energy answered the key question of power provision, getting around Africa’s chronically weak grids with the green, baseload electricity required for digital infrastructure.

Kenya’s president was brought in, addressing the concern of the project’s political viability and ostensibly helping to cut through what would otherwise have been huge amounts of red tape. Microsoft and G42 added institutional and technological heft. Kenya’s state-run power firm even set aside 342 hectares for a “green energy park” to eventually support the data center and other industrial enterprises, Victor Otieno, the company’s principal geologist, said.

Officials in Kenya’s technology ministry told Semafor they held talks with a Microsoft delegation as recently as last month, where data sovereignty and potential partnerships for government service delivery were discussed. But over the course of more than a year of negotiations, little clarity has emerged on the best way to monetize the $1 billion project. The ministry did not respond to requests for updates on the timeline for construction.

Certainly, it makes sense for Kenya’s government to be a major client of the data center’s ultimate services: Step into a government building across much of Africa, and you’re confronted with reams of paper. Digitalizing records across government services — from education to health, land registration to tax records — represents an opportunity. Kenya’s eCitizen platform, whose 13.7 million registered users make up around a quarter of the country’s population, provides a ready-made consumer base. The possibilities seem obvious: one-stop online portals for registering businesses or paying a parking ticket; medical records centralized to manage public health; a move to digital government IDs.

The project was particularly compelling because East Africa’s largest economy has one of the world’s most tech-savvy populations: Kenyans use ChatGPT at the highest rate in the world, according to research published in July.

But Nairobi is also struggling with ballooning debt and juggling fiscal priorities ahead of elections in 2027, against a backdrop of protests over the cost of living: For a publicly listed company like Microsoft, the government is not a valuable enough customer to justify a 1-gigawatt data center. And the relatively low purchasing power of consumers in Kenya — and sub-Saharan Africa more broadly — compared with other regions makes it hard to make a business case for partnering on such projects if the aim is to target profitable users.

By comparison, the question of monetization hasn’t been among China’s primary concerns over the last decade. Beijing decided that investing in African digital infrastructure, through Huawei and other state-linked companies, was in its long-term geoeconomic interests.

With an unclear business model, then, any remaining enthusiasm in Washington for the Olkaria project — and, in all likelihood, the prospect of others like it in Africa — has ebbed.

Ultimately, even in a world of Great Games, the bottom line still matters.

Room for Disagreement

The lack of progress in building the Olkaria data center is part of a stop-and-start trend in infrastructure spending among Big Tech players, who appeared in April to be easing off the rapid expansion that defined the last two years. Microsoft said at the time it was “slowing or pausing” some data center construction, including a $1 billion project in Ohio. The same month, Wells Fargo analysts said Amazon Web Services — the largest US cloud company — had paused some data center lease talks. But more recently, deals appear back on: On Sept. 18, Microsoft said it planned to build the most powerful data center in the world, in Wisconsin, with a $4 billion price tag.

A longer term trend, unrelated to monetizing African consumers, could also be at play: The data center construction boom has been driven by increased demand for computing power. A report by research firm Epoch AI, however, suggests that the supply of high-quality, human-generated data for large language models could be exhausted by 2032, which may prompt developers to train LLMs on smaller datasets, thus reducing the need for investments in large data centers.

The View From UAE

The data center in Kenya is “the kind of thing the G42-Microsoft alliance was built for” as the UAE looks to become a player in the global digital infrastructure race, a Dubai-based technology consultant, who asked not to be named due to ongoing work with government-linked clients, told Semafor.

In recent years, the UAE has included numerous digital infrastructure commitments — such as the data center in Kenya — in bilateral trade agreements with foreign governments: It agrees to lead the financing for the projects, and G42 secures the right to build and sell infrastructure and services to government and commercial entities, according to the consultant. Egypt, Greece, India, and the Philippines are among the nations that have such deals.

“In an instance like East Africa, when Microsoft could be either faced with having to spend big and take on risk, or wait for governments to put together financing for infrastructure, [the Microsoft partnership with G42] gets an easy way in on UAE-built infrastructure,” the person said.

For now, however, the much-touted Kenya deal is looking anything but easy.

Notable

- Huawei unveiled hardware last week that it said could deliver world-class computing power without using Nvidia’s advanced chips, which the South China Morning Post said could “break the supply chokehold” that has constrained Beijing’s AI ambitions.

- “Africa needs vast new power capacity to support an AI-driven economy,” journalist Frank Eleanya wrote in TechCabal, examining whether nuclear power would be the best source of energy for the continent’s data centers.

- KenGen teams are helping other African countries — including Djibouti, Eswatini, and Ethiopia — to assess their geothermal energy potential.

Additional reporting by Martin K.N Siele in Nairobi, Morgan Chalfant in Washington DC, and Reed Albergotti in San Francisco.