The Facts

The U.S. government made one of its biggest-ever bets on emerging climate tech when it handed out $1.2 billion in grants to two projects to capture carbon from the atmosphere. The grants focus on scaling up the carbon-sucking technology (direct air capture, or DAC) itself. But they also take a stance on a debate that has divided the nascent industry: What to do with the carbon once it’s captured?

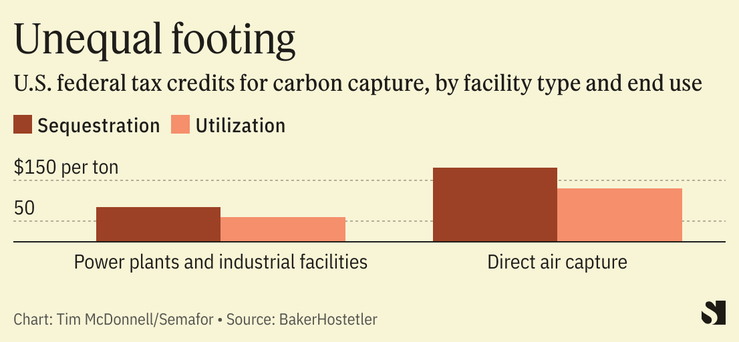

The two grant recipients will bury the carbon in saline aquifers in Texas and Louisiana. That’s in keeping with the general thrust of federal grants and tax credits, which tend to favor “sequestration” over using the carbon as an industrial raw material. But a growing chorus of “carbon utilization” startups say that’s unfair — and they’re coming up with new ways to make money on their own.

Tim’s view

The move to capture carbon from the atmosphere and industrial point sources — something economists broadly agree is essential to meeting global climate goals — is perhaps the best example of the Inflation Reduction Act’s gargantuan impact on an emerging industry. The IRA is at once buffeting and reshaping the world of carbon capture. But niche sectors within the industry are at odds over whether the two kinds of end-use deserve equal treatment under the law.

Today, sequestration is on top. Carbon-capture tax credits, which got a boost in the IRA, are higher when CO2 is sequestered than when it’s utilized. In an interview this week, Benjamin Heard, president of Gulf Coast Sequestration, the company that will offtake CO2 from the Louisiana grant awardee, said the grant essentially dished up an early anchor customer at a time when the company’s facilities are preparing to open.

That disparity makes sense because sequestration is the easiest way to dispose of the greatest volume of CO2, and because utilization is already a relatively more mature market, said Giana Amador, executive director of the Carbon Removal Alliance, a DAC advocacy group.

“Sequestration should definitely be the priority here,” she said. “It’s important for early R&D to not only prove the technical and commercial potential of capture technologies, but also prove the safety and efficacy of different forms of permanent storage on long timescales.”

Utilization also has a bad rap among climate-focused policymakers because the biggest buyer of captured CO2 over the last decade has been oil companies, which can use it to push the final drops out of nearly-dry oil wells. But that’s changing as entrepreneurs cook up new ways to make money from recycled CO2, which they argue will drive broader adoption of carbon capture. And they would rather be seen as a climate solution than in league with oil companies. (A Department of Energy spokesperson said the DAC grant program is open to proposals that serve either utilization or sequestration.)

“The IRA makes people think sequestration is better, which is nonsensical. Surely it makes more sense to do something with the CO2,” said Martin Keighley, CEO of CarbonFree, which installs carbon capture equipment on industrial facilities, then processes the captured gas into other products it can sell, especially a high-purity calcium carbonate that’s used as a filler in food and pharmaceutical products. “We believe there’s a strong case now for [tax credit] parity.”

That view is shared by Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI) and Sen. Bill Cassidy (R-LA) who this spring introduced legislation to equalize tax credits for sequestration and utilization. The bill would not raise the tax credit for oil recovery, effectively creating a three-tiered system.

“Carbon utilization technologies present an opportunity to turn captured carbon dioxide pollution into useful products that would otherwise be made in a carbon-intensive way,” Whitehouse said in an email. “Bringing the value of tax credits for utilization into line with the incentives for sequestration created in the IRA would clear a path for businesses to invest in this promising carbon reduction tool.”

Gregory Constantine, founder of carbon utilization startup Air Company, said companies in this new space shouldn’t wait for taxpayer support, and need to find ways to generate revenue quickly while they scale up the more ambitious parts of their business. In his case, that means vodka: The company sells chic $75 bottles made from captured carbon, which Constantine said generates cash flow to keep the company afloat while it builds up facilities to produce industrial quantities of carbon-neutral ethanol and aviation fuel.

“As more utilization technologies prove viable at scale it will help things like the tax credit evolve over time,” he said.

Quotable

“I sat in the boardroom of U.S. Steel and it blew their minds that we could take their blast furnace gas and turn it into chewing gum.”

— Martin Keighley

The View From Louisiana

Gulf Coast Sequestration’s business model is to sell carbon-storage space by the ton in the underground aquifers it manages — a network that aims to store 300 million tons of CO2 over the next 30 years.

Heard estimated that within 50 miles of his aquifers there are at least 60 million tons of CO2 emissions produced annually from the sprawling network of oil and gas production and processing facilities on the Gulf Coast, and that eventually all of them will need to be captured. The new direct air capture grants will help jump-start the kind of downstream carbon management chain that will facilitate faster adoption of carbon capture across the region, he said.

“Some of those tons will be used for other tech,” he said. “But today the most viable solution is permanent storage.”

Room for Disagreement

Carbon sequestration is also tightly linked to the oil and gas industry, and some climate groups in Louisiana protested that the DAC grants will pose new environmental hazards and could be an excuse for those companies to continue drilling up more fossil fuels. One top recipient was Occidental Petroleum, which is pushing to dominate the U.S. “carbon management” industry and this week spent $1.1 billion to acquire DAC company Carbon Engineering. Smaller federal DAC grantees include Shell and Chevron. In Texas, oil and gas companies have also pushed regulators to adopt looser legal liability standards for carbon sequestration projects.

Notable

- The federal government is also supporting carbon removal by becoming a customer for it. Under a new program reported by Heatmap, the Department of Energy will spend tens of millions of dollars on carbon removal credits.