The Scoop

For decades, Cravath, Swaine & Moore epitomized the white-shoe, corporate law firm. It churned out rainmakers, helped midwife the modern merger market in the 1980s, and advised the likes of IBM, CBS, and Johnson & Johnson.

But now the action, and money, in dealmaking is elsewhere, and Cravath is yielding.

Partners and headhunters for the firm have been fanning out, seeking lawyers experienced in private equity and private lending, which are now the dominant players in M&A and the largest source of fees for many banks and law firms.

Some of those approached said Cravath is offering significant paydays — this from a firm so conservative and averse to the star model that it kept a rigid, seniority-based pay system decades after other firms abandoned it.

There are other signs that Cravath is expanding from its roots. Last year it opened a D.C. office, its only U.S. location outside of New York, and hired former FDIC chair Jelena McWilliams to run it. This year it started hiring local lawyers, trained in English law, for the London outpost it’s had since 1973.

Cravath didn’t respond to a request for comment.

In this article:

Liz’s view

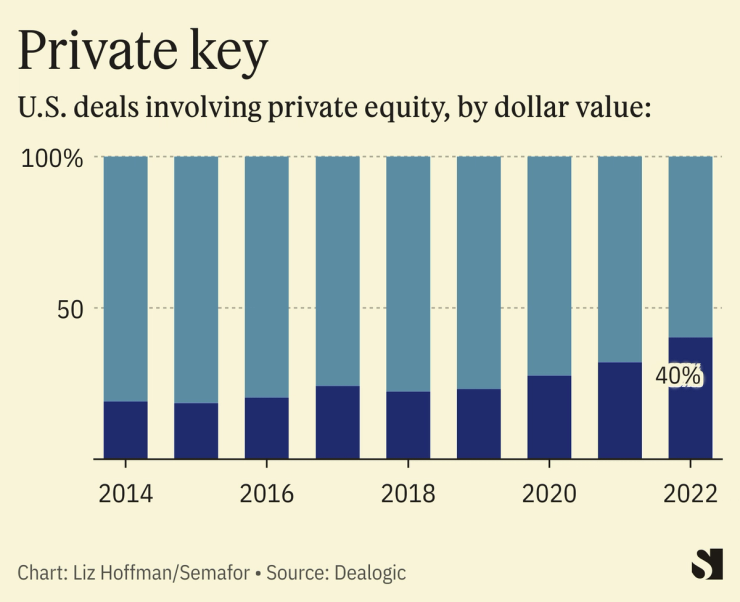

Pitched takeover battles between name-brand public companies drive headlines, but the money is increasingly in serving private firms. Private equity accounted for less than 10% of U.S. deals in the 1990s, according to PWC. Last year, that figure was 40%. And more than 80% of medium-sized buyouts last year were financed by private credit firms, according to McKinsey.

Those clients don’t need boardroom advice. Private-equity lawyers are a more commercial, earthly type. The best can quote junk-bond yields and know who’s buying and selling in the loan market. Blackstone paid Kirkland & Ellis nearly $125 million between 2021 and 2022, securities filings show.

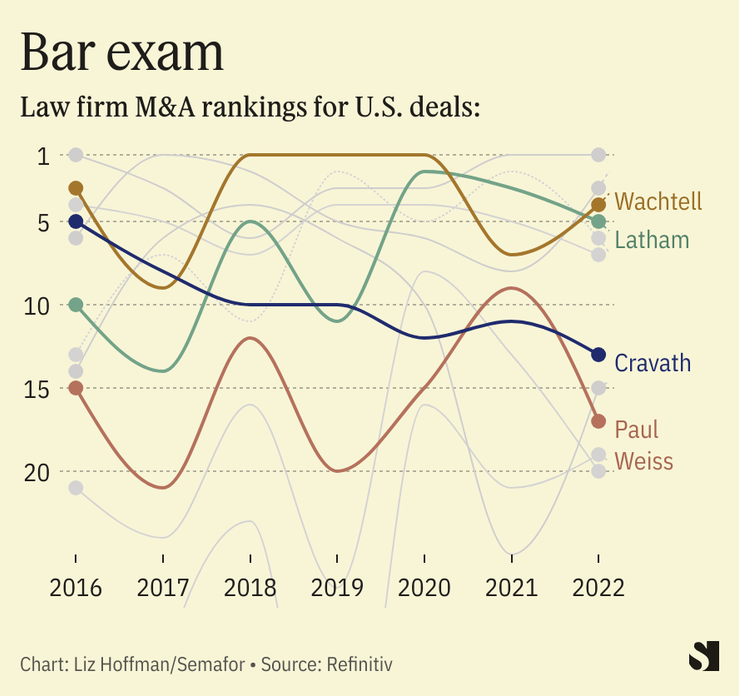

A handful of law firms have reinvented their corporate practices, though mostly in the other direction. Paul Weiss, known for its litigation chops, and Kirkland, for its bankruptcy and private-equity work, have both built leading public-company practices over the past decade, almost entirely by picking off rainmakers from other firms (including Cravath.)

It was once unheard of for lawyers to leave Cravath, and outside hires were extremely rare. The insular culture fed into its elite status but may be part of a bygone era: Recent headlines of departing Cravath partners have all noted their historical rarity.

More broadly, the boutique model, while becoming more popular for bankers, has waned for lawyers. Kirkland has more than 3,000 lawyers; Skadden, more than 1600. Of 15 leading M&A shops in 2022, only two have fewer than 100 partners: Wachtell Lipton and Cravath. There may only be room for one.

Room for Disagreement

Even without a major private-investment practice, Cravath’s revenue is up 16% since 2018, according to The American Lawyer. And the firm remains a go-to for public-company knots. It recently pulled perhaps the thorniest M&A assignment of the year so far, advising the independent directors of EchoStar, controlled by Charlie Ergen, in its sale to Dish, also controlled by Ergen.

Notable

- The Financial Times dug into how Kirkland’s move into private equity helped rake in revenue, but also carried risks.