The Scoop

US companies are rushing to buy solar panels ahead of the Trump administration’s early phaseout of tax credits in a frenzy that could stretch into mid-2026, the head of a top solar hardware marketplace told Semafor. Ultimately, the phaseout could end up helping the same Chinese manufacturers the White House wants to combat.

In June and July, after the One Big Beautiful Bill Act passed Congress, 660 megawatts worth of solar panels traded hands on Anza — which connects manufacturers and distributors of solar panels with utilities, commercial developers, and other large customers — its CEO Mike Hall said. In the previous five months combined, sales amounted to 620 megawatts. Driving the rush, Hall said, is a desire to get ahead of new rules on construction deadlines and foreign supply chains that will drastically raise the cost to build and operate new solar projects.

“Everything has changed since late June,” he said. “Companies are aggressively trying to hedge and protect their projects, and mainly that means you’ve got to buy your stuff early.”

Tim’s view

The Trump administration’s crackdown on renewable energy is just getting started. The best time to start building a new solar project was yesterday, and each passing day raises the risk of crippling new costs.

The OBBBA mandated wind and solar tax credits be phased out much more quickly than was previously planned. Other restrictions quickly followed, including a requirement that major renewables projects get a personal signoff from the interior secretary, the withdrawal of millions of acres of offshore territory from eligibility for wind farms, and, on Friday, a rule that could be used to deny permits for all wind and solar projects on federal land on the basis that they produce less power per acre than fossil or nuclear alternatives.

Other restrictions are coming soon. In mid-August, the Treasury Department is expected to issue a more stringent standard for how far along a renewable energy project must be to qualify as “under construction” and therefore be eligible for tax credits. By the end of the year, projects will also need to adhere to stricter rules to exclude any supply chain links to China or other “foreign entities of concern.” And after July 2026, new projects won’t be able to qualify for tax credits at all. In the meantime, it’s likely that the Commerce Department will slap steep new anti-dumping duties on panels coming from Laos, Indonesia, and India, on top of those it approved during the Biden administration on panels from Malaysia and other Southeast Asian countries.

In the near term, that’s mostly good news for companies like Anza and the solar providers they work with, which are capitalizing on buyers’ fears of impending price spikes to push panels out the door en masse. Hall said Anza is working to add new features to its software platform that will show more details about panels’ provenance, information that could drastically affect a project’s tax liability.

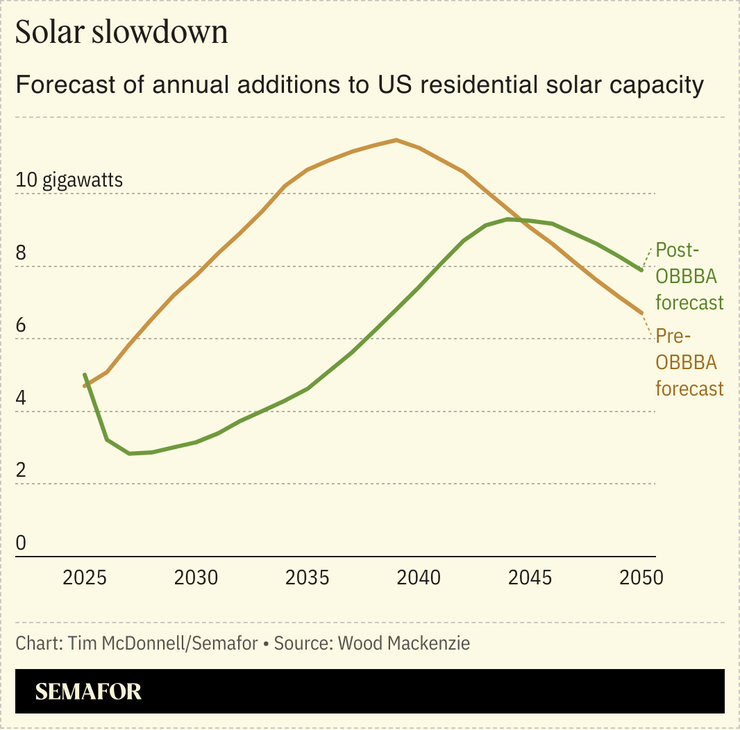

But the rush will be short-lived. Cutting off tax credits and access to foreign suppliers will drive up solar costs and cut into adoption. A Wood Mackenzie analysis published today forecast that US residential solar adoption by 2030 will be 46% lower now than it would have been prior to the OBBBA.

And while new economy-wide and solar-specific tariffs should ostensibly be a tailwind for US solar manufacturers, that sector is in for a rough patch as well, Hall said. According to price data from Anza’s marketplace, prices for US-made solar panels are up to 50% higher per watt than competitors from other countries. For many of the new solar factories planned during the Biden administration, buyers could overcome that gap by tapping a bonus tax credit for US-made panels.

Without that “adder,” the economics of many domestic solar factories won’t make sense, especially as other tariffs on raw materials and components needed for solar factories also make the whole production process more expensive. For projects that start construction after next July and don’t qualify for the credit at all, the “foreign entity of concern” rules become moot. At that point, there’s less reason for developers or manufacturers to avoid doing business with Chinese or China-linked suppliers, which will make US manufacturers less competitive.

“You’ll go back to dealing with Chinese-owned companies, and I fully expect that to happen,” Hall said. “So I don’t think [the Trump administration] is really achieving what they’re trying to achieve.”

Room for Disagreement

Rising power demand and electricity prices, and increasing prices and wait times for gas turbines, mean those solar companies that can survive the tumultuous next few years will still find an enormous market open to them. And for now, some factories are thriving: First Solar, the top US manufacturer, beat Wall Street expectations for its second quarter earnings. “The recent policy and trade developments have, on balance, strengthened First Solar’s relative position,” CEO Mark Widmar told shareholders.

The View From Malaysia

On the opposite end of the supply chain, solar factories that were set up across Asia over the last five years to supply the US are now struggling to stay afloat in the face of crippling tariffs. For Malaysia, one solution is to spur more local demand for solar.

Notable

- Two top Republican senators are blocking Trump nominees for key Treasury Department positions over their frustration with the administration’s handling of renewable energy. John Curtis (R-Utah) and Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa) had fought their colleagues about tax credit cuts but were ultimately forced to relent; now, they want to ensure the Treasury doesn’t make the cuts even deeper.