The News

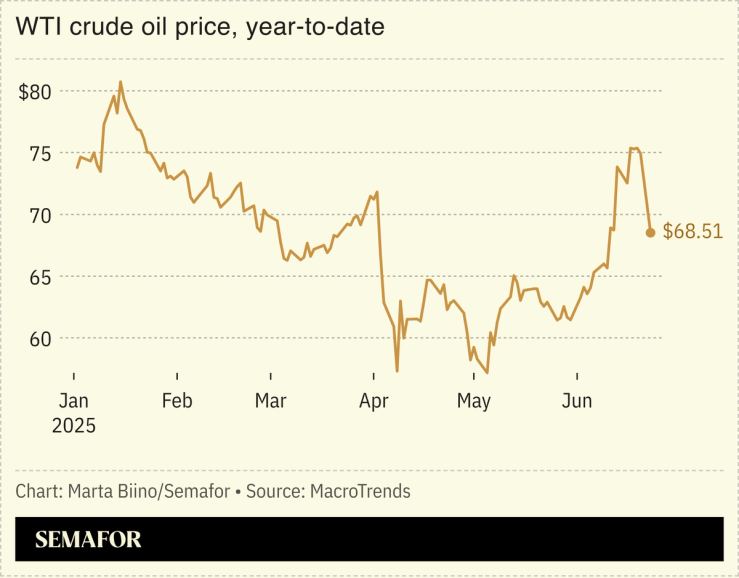

Oil prices fell to their lowest point since Israel and Iran began trading rocket attacks two weeks ago as the two countries reached a fragile ceasefire agreement — despite tensions following American targeting of Iran’s nuclear facilities and Tehran firing rockets against a US military base.

Prices had jumped to a five-month high after hostilities broke out, with traders adding a geopolitical risk premium of up to $12 per barrel on top of the previous trading price of roughly $65 for US and international crude benchmarks. But even at their peak, prices remained far below the triple-digit levels that a broad war in the Middle East threatened to unleash. With a de-escalation of the conflict now looking likely, analysts expect oil prices to fall back to the low $60s.

In this article:

Tim’s view

The fact that the conflict flared up and died down (for now, at least) without an energy crisis speaks to the geopolitical power of “drill, baby, drill.” Ever since the Arab oil embargoes of the 1970s, a full-blown war across the Middle East has been the energy market’s nightmare scenario. Numerous major refineries and shipping terminals are either controlled by Iran or are potential targets for attacks. Tehran has also repeatedly threatened to close the Strait of Hormuz, through which one-third of the world’s seaborne crude oil and a fifth of LNG move daily. That move could have sent oil prices skyrocketing well above $120.

Yet over the past two weeks, higher energy prices were the dog that didn’t bark. One key reason was that the conflict seems to have been resolved relatively quickly, leaving less time for traders to fret about future attacks. But the other key reason was that the record US oil production levels reached under both US President Donald Trump and former President Joe Biden granted Washington a geopolitical insurance policy — while the global clean energy transition leaves exporters like Iran with less leverage.

The US fracking boom of the last decade gave Washington unprecedented sway over the global oil market. As Javier Blas observed in Bloomberg, this month the US even had a week where it didn’t import any Saudi crude for only the second time in the past 50 years. That gives the US president a freer hand to take military risks in the Middle East without fear of blowback for domestic gasoline prices. Trump took advantage of the conflict this week to urge even more US drilling, but with prices relatively muted, American oil companies are already as busy as they’re likely to be.

That gets to the other dynamic at play here: Thanks to the proliferation of EVs, Trump’s trade war, and other factors, the global oil market is already oversupplied. So going into the Israel-Iran conflict, there was headroom for the price to inch up without causing consumer panic. With a growing number of energy alternatives, the world is less sensitive to oil crunches than it once was. Iran, for one, has become almost entirely reliant on China as the customer for 90% of its oil — which means closing the Strait, the primary avenue for those exports, would do Iran at least as much harm as its adversaries. In fact, according to Rystad Energy, crude traffic through the Strait has increased in the past week, likely a strategy by Iran to move oil out of Kharg Island and other export hubs that could have become targets.

Room for Disagreement

Even though the Strait remains open, the risk of closures or attacks there has already caused insurance prices to jump and resulted in a rising number of shipments of non-energy products to be re-routed around the southern tip of Africa. The longer route means more emissions, said Stamatis Tsantanis, CEO of the shipping company Seanergy Maritime Holding, and a greater risk of accidents involving oil tankers in Russia’s sanctions-evading “shadow fleet.”

Notable

- Rising LNG prices due to the conflict are a win for coal. Australian coal sold to markets in Asia is now trading at a 13% discount to LNG, Reuters reports.