The News

Oil prices jumped on Monday despite the decision by OPEC and its partners to increase their production quotas for the third time in as many months. But many analysts remain decidedly bearish about their trajectory over the next couple of years, with far-reaching implications for the US economy and foreign policy.

Brent crude, the global benchmark, is sitting just below $65 per barrel, which is its lowest level since the pandemic, though still high enough for most OPEC and US producers to turn a profit. But with gasoline demand growth in China tapering off, a global economic slowdown from US President Donald Trump’s tariff wars looming, and more OPEC production and export boosts likely in the near future, there’s more downside ahead. Goldman Sachs expects Brent to fall to $60 this year and $56 next year; the political consultancy Eurasia Group sees it going as low as $45 through 2027, pushing the global economy into a prolonged “low-price cycle.”

Tim’s view

A world in which the price of oil falls below $60 for months or years will shake up trade and geopolitical dynamics that have structured the global energy market since the pandemic, affecting the world in ways that are mostly, though not entirely, disadvantageous to the US.

“In this world, the entire concept of who benefits from low energy prices gets turned on its head,” said Henning Gloystein, Eurasia Group’s head of energy and climate, meaning more upside for the Gulf and less for the US.

Among the consequences:

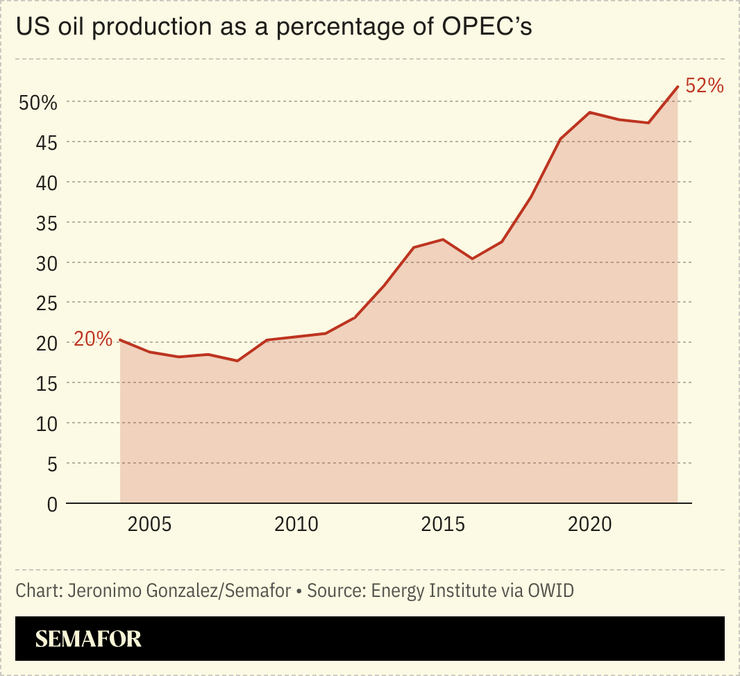

- OPEC gains influence on the price. Saudi Arabia has realized that sticking to low production quotas, a strategy meant to push up the price, instead simply allowed the US to gain market share, especially in crucial Asian markets, Gloystein said. Increased production, and the lower prices that result, will help OPEC regain customers in India and Southeast Asia even if demand in China remains tepid. That will come at a cost to Gulf national budgets, which remain highly oil-reliant: Massive spending plans underway to diversify those budgets mean that “ironically, they need high oil prices to get their economies off of oil,” said Jim Krane, energy research fellow at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy. But lower prices will also push off the moment of peak global demand, which means “Gulf exporters get a bit more time to get their economies in order,” he said. And as low prices force US production to dry up, OPEC will get back some of the influence on prices that it lost because of the shale boom.

- Sanctions pressure on Russia heats up. The risk of skyrocketing oil prices has been a main reason that the US and European Union have struggled to agree and enforce strong sanctions against Russia’s energy sector. When the G7 set a $60 price cap on Russian crude in Dec. 2022, it was designed to keep Russian oil flowing but reduce revenue for the Kremlin. If prices fall below that level, the price cap becomes moot, and some European traders are already forging back into Russia. Now, low prices should make it easier to build political momentum behind an even lower price cap, which French President Emmanuel Macron and others have pushed for, and for the US to enact secondary sanctions on buyers of Russian crude, a plan that Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.) is aggressively shopping with European leaders this week.

- US consumers, producers, and shareholders have competing interests. Cheaper oil is clearly beneficial for US consumers in the near term. But at the current price, American production is already falling, and would dry up even more closer to $50. Given the size of the US oil industry and its bedrock importance to the country’s economy, the consumer benefit of lower prices is likely outweighed by the job losses and reduced tax revenue that would come with an industry contraction, Gloystein said. And below $60, even the biggest oil companies would likely need to trim the dividend payments and share buybacks their shareholders have come to count on.

Room for Disagreement

There are still some bulls in the oil market. Jeff Currie, chief strategy officer for energy pathways at Carlyle Group, told CNBC the conditions are in place for a price rally: OPEC’s actual exports are still low despite the production quota increases, oil storage inventories are low, and the price still includes a significant discount related to Trump’s trade war that is probably overstated relative to the actual economic risk, he said. And in the oil market, low prices today tend to beget higher prices tomorrow, after producers pull back and the supply falls below demand again. “The bear party hasn’t started,” he said.

The View From Alaska

The Trump administration set up an important test for US producers this week when it announced plans to toss a Biden-era restriction on drilling in Alaska. Interior Secretary Doug Burgum framed the Alaska plan as essential to meeting US energy security. But Alaskan oil projects are known for being expensive, and not likely the kind of thing that would pass muster with oil company financial officers with prices below $60.

Notable

- Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney is making new overtures to the oil industry, in the hope that new pipeline and drilling projects will make the country more energy independent from the US. It’s a marked pivot for Carney, who was previously a staunch public advocate for climate action.