The News

A new generation of data centers are being built in Africa’s smaller economies, fueling a $5 billion market opportunity on the world’s fastest growing continent.

Data centers, which house digital infrastructure such as servers and cables, enable faster connections and the ability to store the data of tens of millions of people. In doing so, they improve the experience of using online services such as banking and streaming movies.

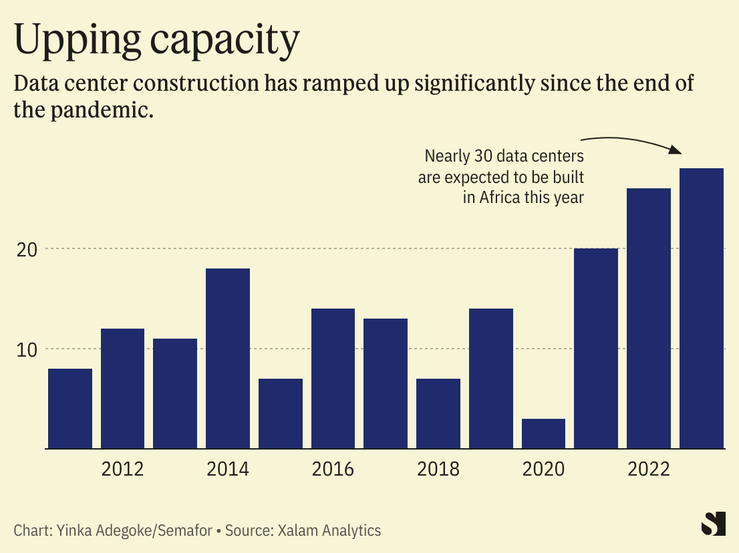

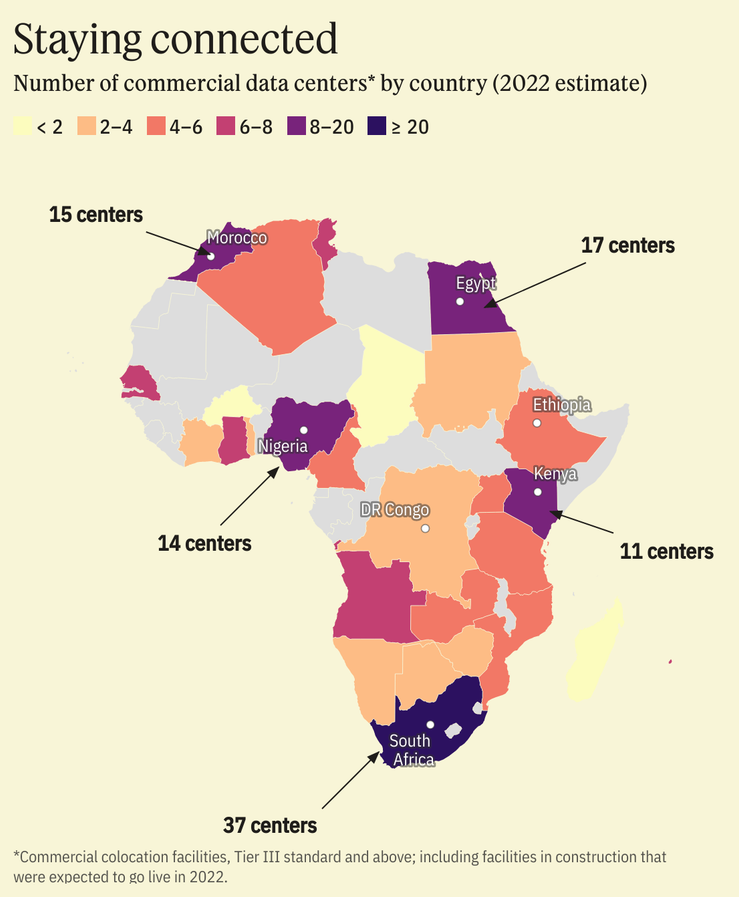

The emergence of local data centers has powered a surge in cloud-based computing in five of Africa’s largest economies — South Africa, Nigeria, Kenya, Egypt and Morocco — in the last five years. Now the number of data centers built in smaller African economies is surging as well, with up to $700 million of capital investment pouring in each year in the past two years, according to data from research firm Xalam Analytics which monitors the industry.

“Within Africa there is a huge discrepancy,” said Sumit Kanodia, investment director at the Emerging Africa Infrastructure Fund (EAIF) which has provided debt capital for data center projects. Data center capacity is “a fraction of where it needs to be” in much of the continent to create opportunities for rapid growth in those areas, he told Semafor Africa.

In April, pan-African data center operator Raxio said it was building and developing sites in Uganda, Ethiopia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Mozambique, Angola, Cote D’Ivoire and Tanzania.

The continent’s data center market by investment is expected to reach $5 billion by 2026, estimates the Africa Data Centres Association trade body.

Alexis’s view

The proliferation of data centers in Africa’s middle tier economies has the potential to redress economic imbalances within the continent and ease challenges around digital sovereignty — the laws applicable to data based on the country in which it is physically located. It could also prevent the region falling further behind in the race to harness artificial intelligence.

Brooks Washington, chief executive of investment firm Roha Group which is backing Raxio’s push into seven African countries, told me it was clear that the continent’s biggest economies needed more data capacity, but there are “another 10 countries with 50 million plus people undergoing a very dynamic digital transformation where there’s actually no capacity.”

Digital plumbing is important. Proximity to the facilities reduces transit costs for internet service providers, enabling them to cut prices paid by customers. With time, this is likely to have a multiplier effect by stimulating economic activity online.

As access to faster, more efficient internet connections spreads across the continent, new clusters of tech hubs are increasingly likely to emerge outside Nigeria, Egypt, Kenya and South Africa. Those nations have hogged up to 76% of the $15.2 billion startup investment in the last five years, according to Africa: The Big Deal, a consultancy that tracks tech investment in the continent.

Africa’s data has traditionally been stored in other parts of the world, via a network of undersea cables, leading to lagging connection times. Google and Facebook are among the big American tech companies that have built some of these cables in recent years, ensuring that data comes from outside the continent and heads back out again. This means personal information about Africans — such as health and financial information — is often stored in servers outside the continent. That can create problems for Africa policymakers by undermining their jurisdiction if, for example, national privacy laws are overridden by those of the nation in which the data is located. Some African governments, like Malawi’s, have been keen to build their own data centers.

There’s also the fear that without this much needed infrastructure, much of the continent could be left behind as businesses, scientists and educators in more advanced economies increasingly use AI to improve efficiency. Data centers provide the internet speeds required to better harness the potential of AI. Without them, many African countries may find themselves locked out of an AI-powered world.

Room for Disagreement

The number of data centers being developed away from Africa’s main tech hubs points to better connectivity, but capacity remains woefully low, given that it is home to nearly a fifth of the world’s population. The entire continent only had five more data centers than the Indian city of Mumbai as of the end of 2022, according to Xalam.

The View From MADAGASCAR

Hassanein Hiridjee, chief executive of pan-African conglomerate Axian group, told Semafor Africa large swathes of the continent were still in need of data centers — even after the construction of sites beyond Africa’s biggest economies.

“There are still around 35 countries to address,” said Hiridjee, whose company operates data centers in Senegal, Tanzania and Madagascar through its Stellarix subsidiary.

Notable

- Data centers could account for around 3% of global carbon emissions by 2025, according to a leading study. Ben DeBow, writing in Forbes, argues that writing more efficient code could optimize software, requiring less energy and therefore reducing the environmental impact of data centers.