The Scene

When Blackstone went public this week in 2007, Tom Wolfe, author of The Bonfire of the Vanities, was on hand at the New York Stock Exchange. He told CNBC the private equity firm’s move to the public markets might spell “the end of capitalism as we know it.”

It didn’t. But looking back, it marked the end of private equity as we knew it.

Going public changed Blackstone and the rivals that followed it: KKR in 2010, then Apollo, Carlyle, and Ares. It served as notice of the end of the industry’s wildcatter days and ushered in the current era of haves and have-nots, a widening gap that threatens to wash out thousands of players over the next decade.

Blackstone and its ilk were not overnight successes as listed companies. Their stock prices languished as shareholders rightly assumed that they sat low on executives’ list of priorities, and behind fund investors and employees.

But over the past decade, these firms reoriented themselves around their stock price, likely because their executives now own a lot of it. They dissolved lucrative but strange partnership structures that had kept their shares out of the S&P 500 index — Blackstone was the first to be admitted, in 2023 — and began emphasizing the steady fees they clip from managing money, rather than the lumpy profits they get from managing it well. They invented a financial metric from whole cloth, “fee-related earnings,” and trained public stockholders to like it. Once they had, the incentives were to manage more and more money.

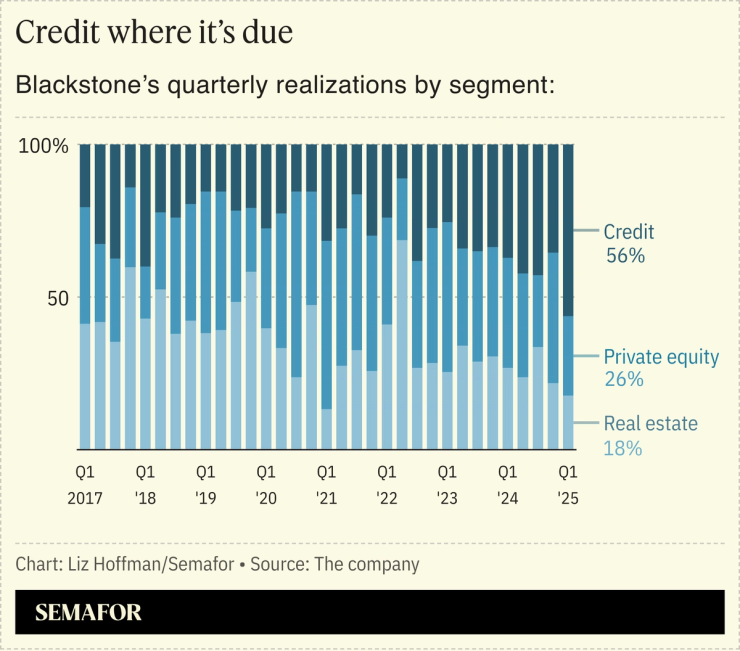

Today’s listed firms are asset-gathering machines. They are still, for the most part, good investors, but their value is increasingly in their size and scope, not their dealmaking savvy. Blackstone hit $1 trillion in client assets and has its sights on $2 trillion. KKR is targeting $1 trillion by 2030, in what looks like a conservative bogey. Corporate buyouts are a shrinking slice of their businesses, dwarfed by fast-growing lending, insurance, real estate, and infrastructure arms.

“Going public was the beginning of the idea that these firms are real businesses,” Joshua Ford Bonnie, who, as a second-year partner at Simpson Thacher & Bartlett, led the Blackstone IPO and others that followed. “It wasn’t just ‘what are the economics from this fund?’ but rather ‘how am I growing this institution?’

“The underlying economic forces have been at their backs, too,” he said, noting the decline of stock-picking mutual funds and the post-2008 regulatory changes that hobbled banks.

Step Back

Bonnie still sees space in the public markets for smaller, niche managers, though a bit of business development hustle is probably at work there. But when you talk to industry executives these days, you don’t hear much about deals. They talk about products (evergreen funds!), distribution (retail!), and the virtues of financial superstores. David Layton, the Partners Group CEO, captured this shift when he predicted that the roughly 11,000 existing private investment firms could shrink to 100 “next-generation platforms” over the next decade.

TPG, the last of the original buyout giants to go public, did so in 2022 with a promise to branch out that it quickly met, buying credit manager Angelo Gordon. I doubt it could today. Even its $220 billion in assets and growing list of “platforms” — there’s that word again — make it undersized, a sign of just how dramatically the industry has changed. Case in point: HPS tried to go public with more than $100 billion in a single business line and couldn’t, at least not at the valuation it wanted. It sold itself instead to BlackRock, the index fund giant that is building its own investing superstore in alternatives.

“Where are the customers’ yachts?” asks the classic finance book, which notes that asset managers tend to make money for themselves whether or not they make money for their clients. The buyout buccaneers of the 1980s were their own clients, bootstrapping their corporate takeovers until their sky-high returns lured in outside money. That transformation is now complete. The barbarians at the gates are just asset managers now — big, and a bit boring. It wasn’t, as Wolfe predicted, the end of capitalism, but the end of a certain flavor of it.