The Scoop

Blue Owl launched with instant credibility and quick success. A 2021 merger of two investment shops brought Wall Street royalty — veterans of Blackstone, KKR, Goldman Sachs, and Neuberger Berman — into an investing superband that raised oceans of money and did deals at a clip.

Two years in, it is already cracking.

A schism has opened along the lines of the union two years ago of Owl Rock, a major player in private credit, and Dyal, the brainchild of Michael Rees, and the biggest player in the lucrative business of collecting stakes in other investment shops.

Blue Owl’s co-CEOs, Doug Ostrover and Marc Lipschultz, who both come from the Owl Rock side of the marriage, have asked Rees to resign after months of growing tensions, people familiar with the matter said. Rees refused, the people said, telling them that he believes his contract is ironclad and has no plans to leave behind the business that he named after his kids 12 years ago.

A quiet reorganization last month made those battle lines explicit. Lipschultz, who had been co-president of the firm with Rees, was elevated to co-CEO, alongside Ostrover. Rees remained a rung down, and two other executives were added as co-presidents beside him.

The reshuffle was disclosed in a securities filing rather than a press release and public rollout, an unusual move for a listed company making changes at the top. (The firm did put out a press release announcing a recent mid-level hire.)

Blue Owl said in the filing the changes “reflect how the company operates its business.” Rees has told friends that the moves were an effort to sideline him and turn up the pressure on him to leave. He has privately fumed at what he believes was a retrade of an original agreement that envisioned Ostrover as CEO, and he and Lipschultz, as his lieutenants, making joint decisions about the direction of the firm.

A Blue Owl spokesperson declined to comment on behalf of the firm and the three executives.

In this article:

Know More

Blue Owl is bigger than household names like TPG and Warburg Pincus, and growing faster than either. It manages $144 billion, up from $47 billion when it went public two years ago.

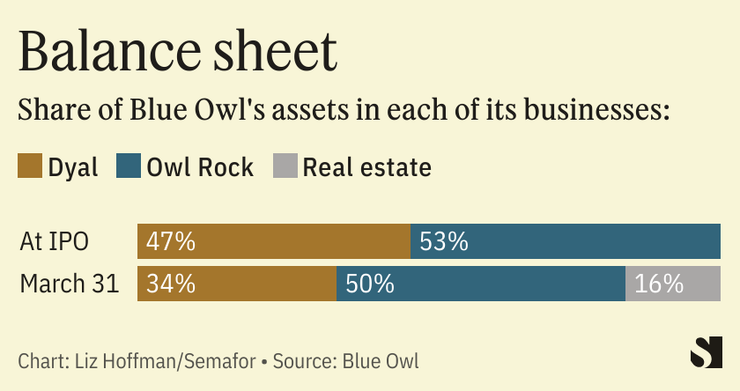

At the time, Dyal and Owl Rock managed roughly $25 billion each, making for a balanced firm. Both have since grown, but Owl Rock’s business of making corporate loans has expanded faster, and the acquisition of a real-estate firm in 2021 further tilted the balance.

Liz’s view

Blue Owl launched with a lot of ego under one roof, and tempers were bound to flare.

Still, this seems foolish all around. Blue Owl has built what every Wall Street executive dreams of: a diversified firm with a lot of permanent capital that throws off billions of dollars in steady fees. Its three legs — private credit, real estate, and the legacy Dyal business — live at the profitable edge of a private-equity industry that is moving away from its roots in leveraged buyouts.

In reporting this story, I found no flashpoint to explain the rift between Rees and his co-founders — just the garden-variety tensions that follow lots of mergers, in this case amplified by big personalities and tribal loyalty. (If you know the backstory, please do get in touch.)

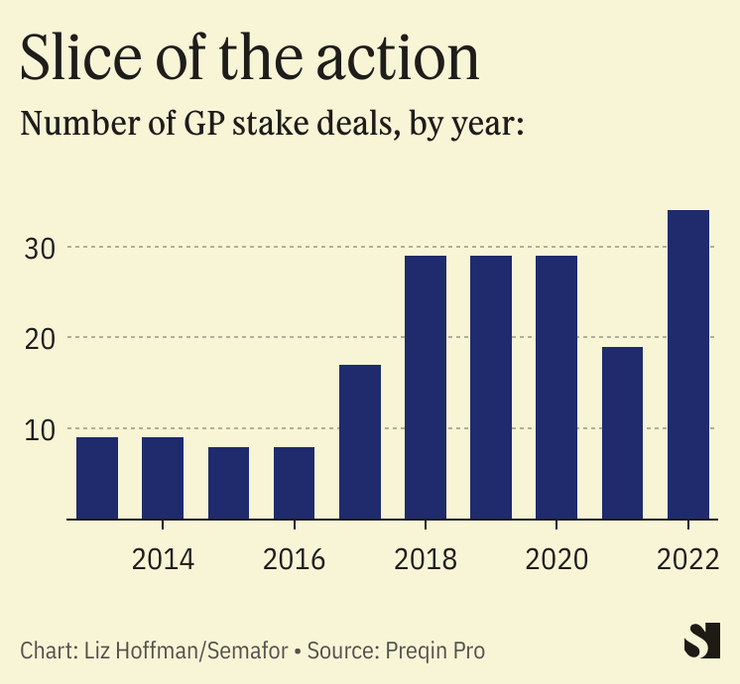

Blue Owl clearly thinks it can shed Rees while keeping his business, which includes stakes in firms like Silver Lake and Vista. But Rees built that book on personal relationships, convincing skeptical private-equity tycoons to take his money. As near as can be said about anyone still on Wall Street these days, Rees created an entire asset class. I wouldn’t be so sure those ties will stay.

Room for Disagreement

Dyal is known for its hands-off approach to the private-equity firms it invests in, so they might not care whether Rees stays or goes. A lot of financial innovations — and Rees’ idea of collecting a stable of investment firm stakes certainly counts, having been copied across Wall Street — start with an impresario-evangelist, and eventually get institutionalized into a more faceless approach.

Notable

- Rees “won favor by acquiring stakes in other firms but made enemies by selling a slice of his own,” the Financial Times wrote in 2021.

- Lending done by firms like Blue Owl, outside of traditional banks, “doesn’t eliminate risk,” The Wall Street Journal wrote in December, “just spreads it around a bit more.”