The Scoop

It seemed like a straightforward case of pandemic fraud.

In May of 2020, a pop-up medical-supply company run by political insiders found itself under federal investigation for failing to provide $457 million worth of masks to California’s government.

________________________________________________

But the story of Blue Flame Medical is a stranger one and is now in front of one of the country’s top financial regulators. It has pulled a tiny Virginia lender and the largest bank in the country, JPMorgan, into a dispute that could carry hundreds of millions of dollars in fines.

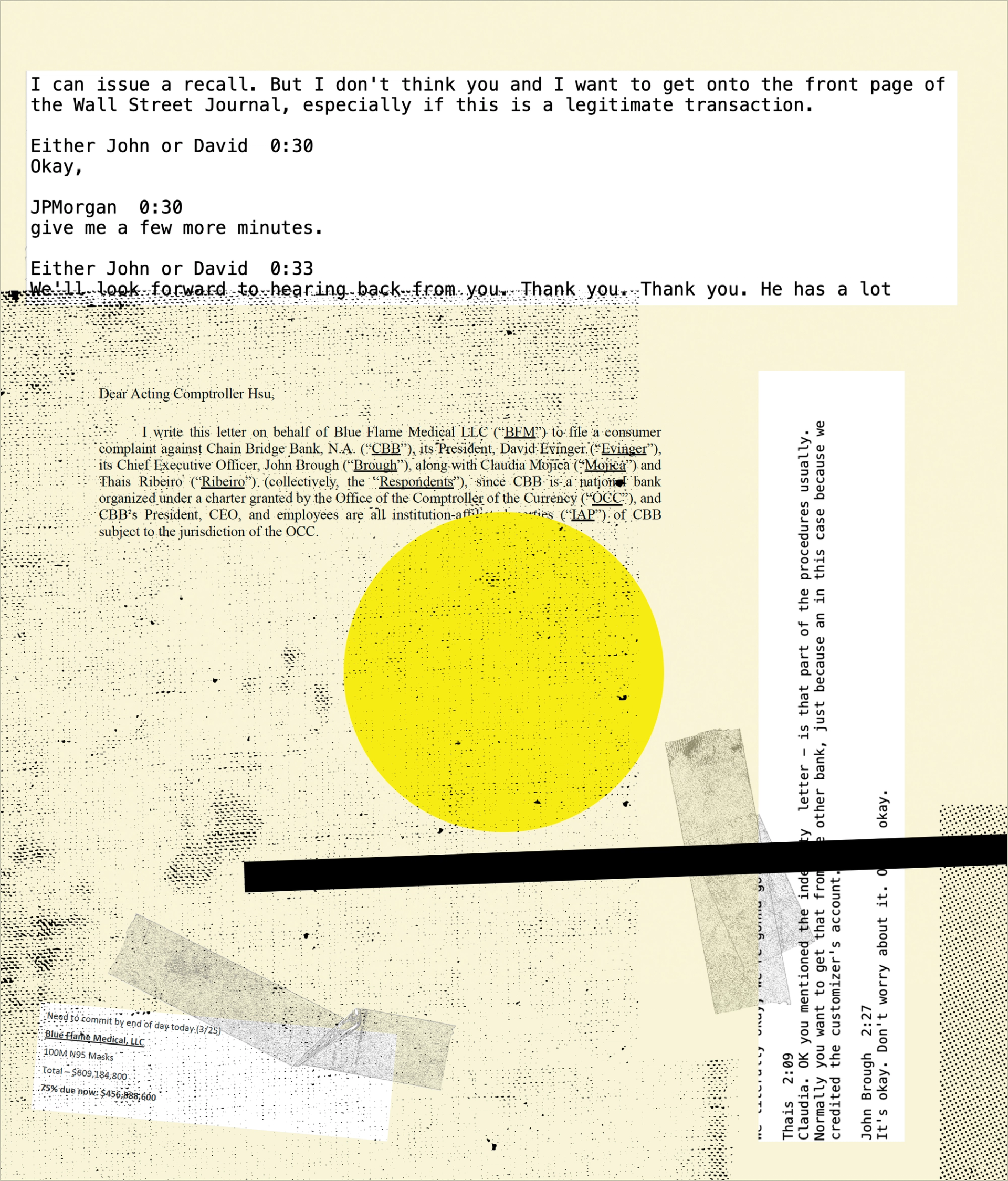

Blue Flame’s co-founder says the Virginia bank, aided by JPMorgan, illegally reversed a $457 million payment it received from the government of California, setting off a chain reaction that put his company out of business. Internal bank records and emails, recorded phone calls, and depositions reviewed by Semafor show that while fraud concerns played a role, the decision to unwind the payment was primarily driven by the sudden realization by executives of Chain Bridge Bank, which housed Blue Flame’s account, that it simply couldn’t hold that much money.

“I hope you’re using ‘M’ as roman numeral for thousands and not ‘M’ for millions,” a Chain Bridge executive wrote a colleague after being told that the wire was on the way. “That’s half our asset size and [there] could be problems on our capital ratios.”

His colleague responded that Chain Bridge’s CEO and its president “are very skeptical about this. If it ends up being real…they said we would need it off of the books asap.”

Their panic was justified. Chain Bridge was founded in 2007 by former Sen. Peter Fitzgerald, an Illinois Republican, and has become the party’s favored bank. Donald Trump’s 2024 campaign has its main account there, as did Ron DeSantis’ presidential run, the Republican National Committee and dozens of other PACs and congressional candidates, campaign-finance filings show. It’s thinking about going public.

But it’s a tiny bank. It made just $9 million in profits last year, and in early 2020 had just $762 million of deposits, supported by $64 million of capital. Even parked in riskless Treasury bills, a deposit as big as Blue Flame’s would have put the bank dangerously close to, or more likely over, federal limits, which invites OCC penalties and heavy supervision.

So off the books it went, four hours after it came in, despite the fact that it had been credited to Blue Flame’s account — making it essentially untouchable under banking laws. At Chain Bridge’s request, California’s bankers at JPMorgan recalled the funds without the approval of the state treasurer.

“I can issue a recall,” a senior JPMorgan banker told Chain Bridge’s CEO, according to a recording of the conversation, “but I don’t think you and I want to get onto the front page of the Wall Street Journal, especially if this is a legitimate transaction.”

________________________________________________

Two months later, after Blue Flame had been publicly tarred as a suspicious actor, the state treasurer sent JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon an email thanking him for “protecting public money.”

Chain Bridge and its executives, along with JPMorgan, declined to comment.

The pandemic turned banks into conduits for a flood of money that they mostly didn’t want and didn’t quite know what to do with. That was especially true in its dark and chaotic early days, when Washington was pushing trillions of dollars into an economy in freefall.

Big banks prioritized their existing clients for government loans, delaying aid where it was most needed. Financial newbies threw open their doors, which is how firms with names like Womply and Kabbage became outsized vectors of fraud. Thousands of people had bank accounts mistakenly frozen, while the Justice Department is still chasing down true scammers. As savings rates spiked, bank coffers swelled with deposits; Silicon Valley Bank memorably used them to buy long-dated bonds, lighting a fuse that blew last spring.

Blue Flame’s co-founder, John Thomas, knows how it all looks. “Were we opportunistic? Yes,” he said in an interview last month in Washington. “Did we intend to and have the ability to fulfill those contracts? Yes.” He said Blue Flame stood to make about $138 million from the California deal.

The US Justice Department, tipped off by Chain Bridge, sent subpoenas to Blue Flame’s government clients, one of which ended up in the hands of a Washington Post reporter. Blue Flame’s customers canceled their contracts, Thomas said, adding that he refunded each one of them, in at least one case swallowing $40,000 in credit-card processing fees. California held a hearing, where a procurement official said that he didn’t know about Blue Flame’s short history when he approved the deal. The entire episode receded into the jungle of widespread pandemic fraud, waste, and abuse, the price tag of which the Associated Press has pegged at more than $400 billion.

In a complaint filed this week with the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, Thomas is urging the agency to investigate Chain Bridge’s actions and order it to reimburse him $457 million. Four members of Congress have signed letters supporting his cause.

“Our bank put us out of business,” Thomas said.

The material cited in this story largely comes from filings in federal court in Virginia, where Blue Flame sued Chain Bridge in 2020. A judge ruled in 2022 that Chain Bridge had wrongly wired out the money and suggested that Chain Bridge’s executives misled JPMorgan into believing that the money hadn’t been credited to Blue Flame’s account. She didn’t award damages because she found Blue Flame wouldn’t have been able to deliver the masks anyway.

Thomas said the company delivered 13 million masks to state and local governments, and provided videos of deliveries in Chicago and Maryland. “Not a single item has ever been returned,” Thomas said.

In this article:

Know More

Blue Flame was founded in March 2020 by Thomas, a Republican strategist, and Mike Gula, a Republican fundraiser. It quickly struck deals with several states to deliver N95 masks and signed contracts with two established Chinese manufacturers. On March 26, California wired $457 million from its bank account at JPMorgan to Blue Flame’s account at Chain Bridge as a pre-payment for 100 million masks.

When the Blue Flame wire came in, internal emails show that bank employees tried to shift the money to another bank using a network called IntraFi. But they hadn’t realized that IntraFi’s daily limit is $125 million, which would leave $332 million on Chain Bridge’s balance sheet just days before it needed to file its quarterly report to regulators.

“Do not contact the client about this wire,” Chain Bridge CEO John Brough wrote in an internal email to Chain Bridge account managers a few minutes later. When one of them replied that the bank had already credited Blue Flame’s account, Chain Bridge’s President David Evinger said: “It’s okay, don’t worry about it.”

Chain Bridge tried to get California’s treasurer’s office to recall the money, but was told twice that the transaction was authorized. “We confirm that this is a legitimate transfer,” an employee from the California Department of General Services told Evinger, in a recorded call.

The two executives next pressed California’s bankers at JPMorgan to make a formal request for the money to be sent back. JPMorgan, which had suspicions of its own, ultimately sent the recall before it had its client’s approval, and the money was wired back to California’s account that afternoon. “It wasn’t anything that I had communicated to Chase,” the California payments officer who oversaw the deal later testified. “I was told the wire was coming back.”

JPMorgan later sued California to recoup $6 million in Chain Bridge’s legal fees it paid because it had indemnified Chain Bridge for the wire transfer — standard industry practice. It dropped the case last month.

Two weeks after the Blue Flame incident, California signed a $1 billion contract with BYD, the Chinese electric-battery company, to produce hundreds of millions of masks. The subsidiary it signed a contract with had been created on March 10, 2020. BYD missed its deadline twice.

Liz’s view

This mess helps explain why banks wanted little to do with pandemic relief and were pressed reluctantly into service to distribute the $4.6 trillion of government aid pumped into the economy in response to Covid-19.

They were slow to embrace the Small Business Administration’s Paycheck Protection Program, which covered payroll for millions of US businesses, over concerns about fraud risk that might follow them for years. “An uncertain payday, extra hours worked and potential legal or reputational risk combine to raise the question,” S&P wrote shortly after the program’s launch. “Will the millions in fees be adequate compensation?”

If it all feels a bit self-serving and unpatriotic, it is. But Bank of America’s $4 billion purchase of mortgage lender Countrywide in 2008 has cost it $50 billion in fines since then. Jamie Dimon has lasting regrets about rescuing Bear Stearns and Washington Mutual during the financial crisis. (First Republic, which he bought in a fire sale last spring, was a much cleaner bank.) There’s a reason banks don’t love being pressed into service.

The Chain Bridge mess is also a reminder that the long tail of US banks is really long. There are 4,500 banks in the country, the vast majority of them with less than $1 billion in assets. They can’t make the same investments in technology, compliance, and risk management as $3.5 trillion JPMorgan. That’s fine as long as they stick to serving small customers with small ambitions, but sometimes they don’t.

Chain Bridge had never seen a deposit this big and didn’t know that it couldn’t handle it. With small banks under pressure from higher interest rates and souring real estate, we’ll find out over the next year or two what other competencies they’ve been short on.