The News

Morgan Stanley CEO James Gorman said Friday he’ll step down in the next year, and added that there are three strong candidates who could replace him.

Gorman, who turns 65 this summer, is sharpening a timeline that has been consistent if slightly fuzzy. (He told me in 2018 that he planned to stay three to five more years, then repeated that in 2021.)

He has wanted to avoid the succession mess of the 2000s, when a blood feud between Phil Purcell and John Mack paralyzed Morgan Stanley for years and, after Mack rode back in, helped encourage the excessive risk-taking that nearly proved fatal in 2008.

There was some question whether ego might trump discipline and that timeline might turn into a Jamie Dimon-esque rolling five-year clock. But the Australian Gorman is sticking to it, and the succession race that started two summers ago, when he elevated two lieutenants to co-president, and sharpened in January, when another candidate, Jon Pruzan, left the firm, now kicks into middle gear.

Liz’s view

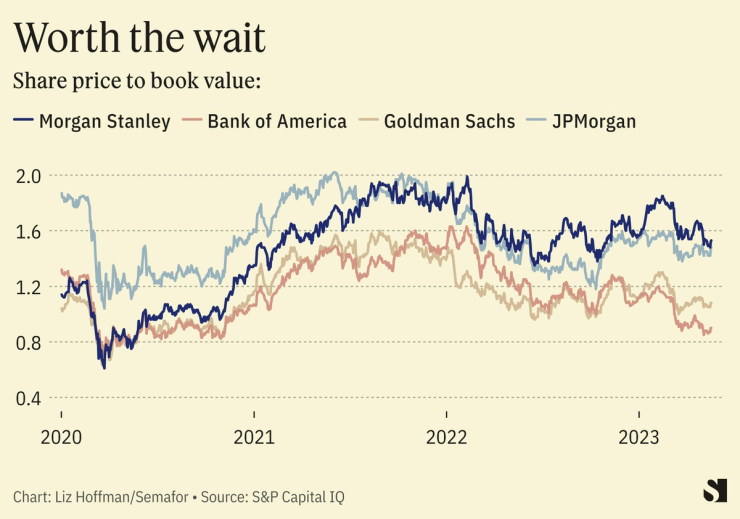

Barring a screw-up now, Gorman’s tenure will go down as one of the most successful among modern CEOs, and not just on Wall Street.

It’s hard to overstate just what a mess Morgan Stanley was when he got the job in 2010. Its stock had hit an all-time low of $6.71 (there is a commemorative tie, courtesy of Gorman’s dapper former No. 2, Colm Kelleher, that involves waterfowl and “The Twelve Days of Christmas”) and Moody’s downgraded the firm’s debt. For years after the 2008 crisis, Morgan Stanley remained Wall Street’s weakling, lurching from one mess to another and unable to win back investors.

Gorman’s strategy of cutting back on risky trading and going hard into the steadier business of money management was clearly correct and has now been copied by everyone from Goldman Sachs to Blackstone.

He was early to see that, coming out of 2008, both regulators and shareholders would prefer steady, lower-octane businesses to the profit pyrotechnics of the last decade. A former McKinsey consultant, he loved the wealth-management business, despite never having slapped a back in his entire life, and made it the engine of a new Morgan Stanley that is now one of Wall Street’s consistently best performers. (Outfoxing Vikram Pandit and getting Smith Barney, Citigroup’s giant wealth brokerage, for a song didn’t hurt.)

He could be aloof and peevishly analytical. “You’ll never hear him say ‘call me Jimmy,’ it’s always James,” David Rubenstein told me for this 2018 profile, and he discontinued Mack’s tradition of dining in the company cafeteria. The firm’s bigger egos, like investment banker Paul Taubman and wealth-management executive Greg Fleming, departed.

He also brought a discipline that had been sorely missing. Gorman writes the firm’s daily revenue figures longhand each night, tucking the looseleaf pages into a folder. I don’t know if he still does, but for a while he kept a list of every Spotify song he played on his desk, right next to a list of his New Year’s resolutions.

He was more cautious about moving into the white space created after Morgan Stanley was transformed at gunpoint into a bank holding company in 2008. Goldman Sachs, in the same boat, eventually grabbed onto its new banking license with both hands, and is now trying to unwind a disastrous foray into consumer banking (one that Gorman thought was idiotic, and would say as much to anyone who asked.)

Morgan Stanley stayed out of the toaster game and struck one shrewd acquisition after another. Solium, for $900 million, locked down a key distribution channel for its wealth products. Eaton Vance, for $7 billion, turned its subscale asset-management arm into a player.

Even E*Trade, bought for a hefty $13 billion at the peak of the pre-pandemic market, in February 2020, has paid for itself, bringing 5 million new clients and some excess deposits that Morgan Stanley has redeployed into loans to its wealthy clients.

For any CEO, the key is not overstaying the welcome. Next year, Gorman will have been in the seat for 14 years and reshaped the firm — the “architect of the reengineered success story that is Morgan Stanley,” Kelleher, his longtime deputy and now UBS’s executive chairman, told me today.

On a side note, Gorman said today that he’ll stay on as executive chairman. I’ve never understood why new CEOs often get the chairman’s job as well — they could use extra supervision — but I’ll also note that Gorman eventually found Mack, who remained chairman for almost two years, to be a little meddlesome.

Know More

The three candidates to replace him are Ted Pick, a seasoned trading hand with some rough edges; Andy Saperstein, a blocking-and-tackling operator who came up through the wealth arm by way of McKinsey, like Gorman; and Dan Simkowitz, a former capital-markets banker who runs the firm’s $1.4 trillion money-management arm.

The job has seemed for years like Pick’s to lose, and Pick and Saperstein were named co-presidents in 2021. But Gorman has always thought highly of Simkowitz, who reported directly to the CEO rather than up through Kelleher and was paid more in most years than the firm’s CFO.

As today’s announcement — not quite news, delivered at the firm’s annual meeting, normally a humdrum affair — shows, Morgan Stanley under Gorman is a no-drama place, and the way to get Gorman’s job is to pretend you don’t want it. This will be a Wall Street succession race in which nobody actually appears to be running.

Room for Disagreement

If there’s a mark on his tenure, it’s Morgan Stanley’s lack of diversity. All three contenders for Gorman’s job are white men, and a series of women have left the firm over the years including Ruth Porat, who went on to be CFO of Google, and Celeste Mellet, who is now at Global Infrastructure Partners.

Dimon’s successor looks likely to be one of two senior women at JPMorgan, who co-run the firm’s consumer banking arm. Citigroup’s Jane Fraser became the first woman to run a major U.S. bank in 2021.

The View From Tokyo

A quiet success of Gorman’s has been keeping Mitsubishi, which took a 22% stake in Morgan Stanley during the financial crisis, onside. That has required twice-a-year meetings between top executives, ping-ponging between New York and Tokyo. (In our occasional lunches at 1585 Broadway, when I covered the firm for The Wall Street Journal, I learned quickly to order the sushi.)

Their joint venture sets Morgan Stanley up to benefit from the Japanese retirement boom. Mitsubishi’s huge balance sheet has helped Morgan Stanley punch above its weight in the corporate lending market, and any CEO would kill for a friendly 22% shareholder with no plans to sell.

Correction

Dan Simkowitz was paid more in some years than Morgan Stanley’s CFO, not its CEO, and we’ve updated the story to correct Piepszak’s title.

Notable

- Gorman belongs to a crew of what the Financial Times’ Josh Franklin and Imani Moise called “forever CEOs” that includes Dimon and Bank of America’s Brian Moynihan.

- Bloomberg profiled Saperstein, a pool-and-patio type who hides his Harvard-and-Wharton pedigree under an unassuming air and pontoon-boat vacations in the Finger Lakes.

- Gorman talked about Morgan Stanley’s ambitions in Japan in an interview with Nikkei last month.