The Scene

Hedge fund investor Parag Vora is already ahead in his fight with a $2.4 billion casino empire. But he’s not leaving the table.

In the five months since his fund, HG Vora, launched a fight at Penn Entertainment, he has been handed two board seats at the company, which runs 42 casinos across the US and ESPN’s sports-betting arm, and pushed the company into a hefty stock buyback.

At a moment when many activist investors would take their winnings, Vora is suing Penn, which he says conspired with state regulators to stymie his campaign at the company. The fight has put him on the wrong side of powerful gaming commissioners in several states — some with the power to arrest rule-breakers — as he fights in federal court for the right to seek a board seat that no longer exists. It’s a tough hand.

If his tenacity pays off, he’ll have cracked an industry that has long been immune from shareholder pressures, thanks to a stringent state-by-state licensing system that is deeply suspicious of outsiders — a legacy of a time when organized crime’s influence was heavy. That could open the door to other activist investors to target gaming companies at a time of uncertainty wrought by online competition that has already begun to create winners and losers.

Vora, who had never launched a public board fight before now, has accused Penn of violating Pennsylvania laws when it eliminated one open board seat ahead of its 2025 meeting. The hedge fund also alleged, without providing specifics, that Penn lobbied state regulators to prevent Vora from obtaining the licenses it needs, an allegation a person close to Penn denied.

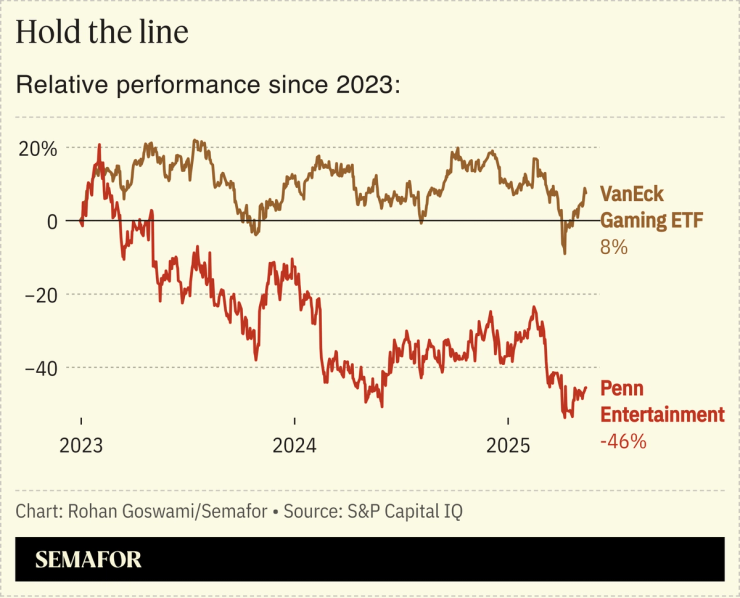

The fight goes back to the end of 2023, when a series of blunders — including buying Barstool Sports for $500 million and then selling back to Dave Portnoy for $1, plus a tax writeoff — hit Penn’s stock price and prompted Vora to launch his campaign. His firm built an 18.5% stake in the company and announced in late 2023 its intentions to push for changes.

That ran afoul of laws in several states, which require investors to clear such a move with gaming commissions. By early 2024 Vora was fielding questions from regulators running background checks and, in at least one case, seeking his trading records, according to people familiar with the matter. Massachusetts proved a particular obstacle, not granting the firm a license in time for them to run a fight at either Penn’s 2024 or 2025 shareholder meetings.

To circumvent those requirements, earlier this year, HG Vora decreased its stock holdings from 18.5% to below the 5% threshold that requires a license. It nominated three candidates to Penn’s board and began girding up for a fight. Both sides began private negotiations about a possible settlement — standard fare when an activist goes full tilt.

In this article:

Know More

That’s where things get contentious. Penn says that it interviewed all three of HG Vora’s director candidates and offered to put two of them on Penn’s board. Vora demanded either all three of his nominees be seated on the board or that the company commit to making “governance and strategic changes” — essentially, hanging what amounts to a for-sale sign on the company, alongside the two offered seats.

Penn went ahead and asked Vora’s two candidates if they wanted to join the casino company’s board anyway, and both agreed. The company eliminated a third seat, prompting Vora to sue the gaming company in Pennsylvania last week.

The hedge fund in a statement last week called the move “a self-serving action with no legitimate corporate purpose” and that “only benefits its incumbent directors.”

Hitting back Thursday, Penn described Vora’s efforts as a “blunderbuss campaign” in a fight letter sent to shareholders. “HG Vora has consistently taken action that has violated state gaming requirements,” Penn wrote, accusing the firm of complying with the letter, but not the spirit, of the law by cutting its stock holdings in Penn but maintaining its economic exposure through financial contracts. It pointed out that HG Vora was also fined by the SEC over disclosure issues at another company it invested in.

Spokespeople for both sides declined to comment further.

Rohan’s view

You have to know when to fold ’em. Vora is running a campaign for a seat that doesn’t exist anymore, something that is logistically impossible, barring a heavy-handed court ruling, and possibly not allowed under SEC regulations. Most activists would rejoice at getting 25% of a company’s board — historically, more than enough to make some changes, assuming their ideas are good. But not Vora.

Big picture, Vora’s gambit could open up a new playbook at casino companies — a seismic shift in a sector that, like big banks that are subject to capital rules, has been protected from dissident shareholders. (The last big proxy fight at a casino company was at Wynn Resorts, when Elaine Wynn — a longtime shareholder licensed by Nevada — took her case to investors in an effort to oust a longtime board member she perceived as too close to her ex-husband, who was accused of sexual misconduct. She lost the fight but managed to get board change nonetheless.)

But if he continues to push along this path, he runs the risk of bringing regulators eager to protect their beat down on his head.