The News

The disqualification of Côte d’Ivoire’s main opposition candidate from the race to become the country’s next president could undermine the nation’s reputation as a stable investment hub, his lawyer told Semafor.

A court ruling last month barred former Credit Suisse CEO Tidjane Thiam, leader of the Democratic Party of Ivory Coast (PDCI), from running in October’s presidential election. He revoked his previous French citizenship in February, with the request approved the following month. But the court ruled that he didn’t revoke his French citizenship early enough to qualify for this year’s vote..

The decision “sends a devastating signal,” Thiam’s lawyer, Mathias Chichportich, told Semafor. Investors may struggle to trust a state that disregards its own laws, he argued, adding that political and legal uncertainty creates instability that may deter investment.

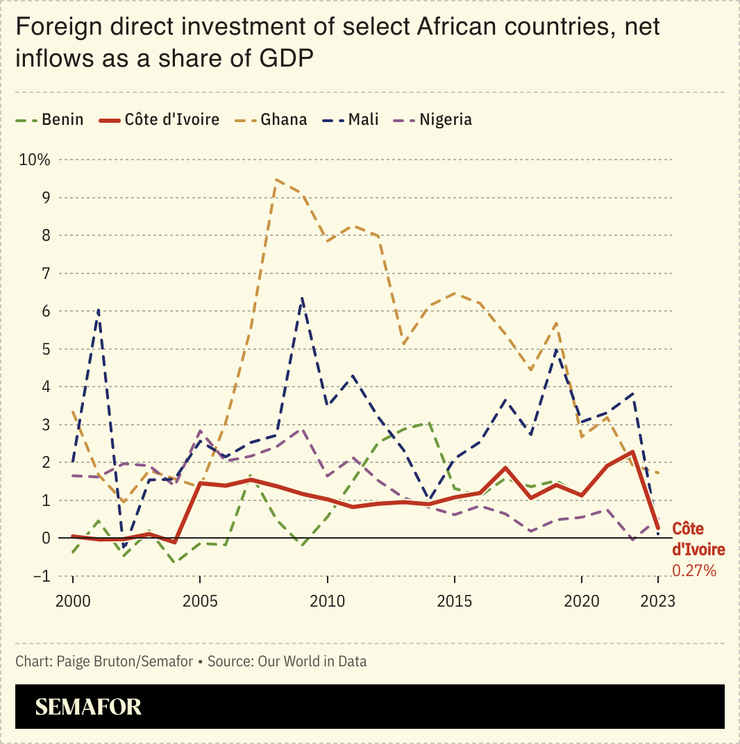

In a glowing April report, the International Monetary Fund said Côte d’Ivoire had emerged as an “engine of growth and stability” in the eight-country West African Economic and Monetary Union of Francophone African countries. GDP growth in the country averaged 6.4% over the past decade, around 3 percentage points higher than the average for sub-Saharan Africa. Côte d’Ivoire also attracts nearly 30% of foreign direct investment in WAEMU — more than any other nation in the group — according to data from the UN’s trade and development body.

Analysts warn that Thiam’s disqualification, amid uncertainty over whether 83-year-old President Alassane Ouattara will seek a fourth term, could lead to damaging instability in Francophone West Africa’s biggest economy. “Thiam’s disqualification sends a negative signal for a country like Côte d’Ivoire, which otherwise enjoys strong governance indicators in the region,” said Aroni Chaudhuri, Africa economist at the French credit insurer Coface.

Know More

Thiam’s exclusion stems from a legal complaint filed by private citizens citing a rarely used clause in the 1961 Nationality Code. The law states that any adult who acquires another nationality automatically forfeits Ivorian citizenship. Thiam is exploring ways in which to mount an appeal, according to Chichportich.

He is the fourth major political figure in Côte d’Ivoire barred from running for president, after former President Laurent Gbagbo, former Prime Minister Guillaume Soro, and former Youth Minister Charles Blé Goudé.

Step Back

Côte d’Ivoire has wrestled with bouts of insecurity since the country descended into a bloody civil war in 2002 that lasted five years. Ouattara, who took office in 2011 after months of violence that followed his predecessor’s refusal to accept electoral defeat, has presided over a period of economic growth that has outstripped other countries in the region.

But Ouattara’s controversial decision to seek a third term — a move many opposition parties viewed as unconstitutional — triggered unrest in 2020.

“Until now, the consensus was that this election cycle would be calmer than in 2020, which saw violence,” said Chaudhuri. “But even without unrest, uncertainty over how the vote will be conducted can impact consumption and investment — as seen in Senegal, where growth slowed and consumption fell during the 2024 election period.”

Joël’s view

A broader concern lies beyond Thiam’s case: The sudden enforcement of dormant legal provisions. The particular clause invoked against him was almost never used against political figures — except for a case in 2011 — and its reactivation raises questions about what other long-overlooked laws could be resurrected for political (or business) ends.

The Abidjan court ruled in April that Thiam lost his Ivorian citizenship in 1987 when he became French, only regaining it in March 2025 after he renounced that nationality — too late to qualify for the late 2024 electoral roll update.

Chichportich, Thiam’s lawyer, argues that his client’s dual nationality was long known and never contested, even during his tenure as a minister in the 1990s. Thiam has also pointed out that half of the country’s football team holds dual citizenship — and that ignoring such realities would undermine the legitimacy of many public figures and national symbols.

Questions of nationality — or Ivoirité — have been used to sideline political opponents in Côte d’Ivoire for more than a generation. Former President Henri Konan Bédié was accused of having a Ghanaian father. Thiam’s case shows how arcane legal precedents could be used to great effect to undermine high-profile individuals.

Room for Disagreement

Some, including within Thiam’s party, argue that he should have anticipated the legal outcome and renounced his French citizenship after being elected PDCI president in December 2023.

One adviser to French companies in Abidjan, speaking on condition of anonymity, told Semafor: “Investors like predictability. If the Thiam decision doesn’t cause turbulence, the economy keeps growing, and the country stays on a steady course, no one will make a fuss — aside from the standard formal statements from Western embassies. Everyone has their role.”

The View From The Business Community

“Among many business leaders, especially SME [small and medium enterprise] heads who lived through the 2010 crisis, there’s real fear and apprehension,” said Georges Yao Yao, co-founder of Y3 Audit & Conseils. “But there’s also a shared sense that, given all the progress and investment since 2011, there are strong incentives not to risk sliding backwards.”

Notable

- The “Thiam saga” shows how identity politics can still weigh heavily in Côte d’Ivoire, wrote Chatham House consulting fellow Paul Melly in a BBC article.