A major part of the Trump administration’s plan to sell national assets is moving forward, with consequences for big telecom companies. Republicans are working to authorize an auction of wireless spectrum as part of the “big, beautiful bill” that would enact the president’s domestic agenda.

Renewing the Federal Communications Commission’s ability to license out airwaves is the first step towards opening up tens of billions of dollars worth of spectrum, currently reserved for the Defense Department, for commercial use. Proponents including Sen. Ted Cruz say it could raise $100 billion that could be used for border security.

It’s part of a broad push from the White House to privatize huge swaths of the economy — what Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has called “monetizing the US balance sheet.” The idea is to sell off, borrow against, or otherwise slap a price tag on everything from gold reserves to government buildings to national art collections and grazing lands, while pushing thousands of federal workers into “higher productivity jobs in the private sector.”

The idea is gaining purchase with financiers, even those not ideologically aligned with much of the White House’s agenda. “You think about the Grand Canyon or the White House, things like that that are out there that are part of our nation,” Ariel Investments co-CEO John Rogers told Semafor last month. “The value of those assets have grown and compounded over the years.”

The questions now around a potential spectrum auction: Who’s bidding? And will the taxpayer actually benefit?

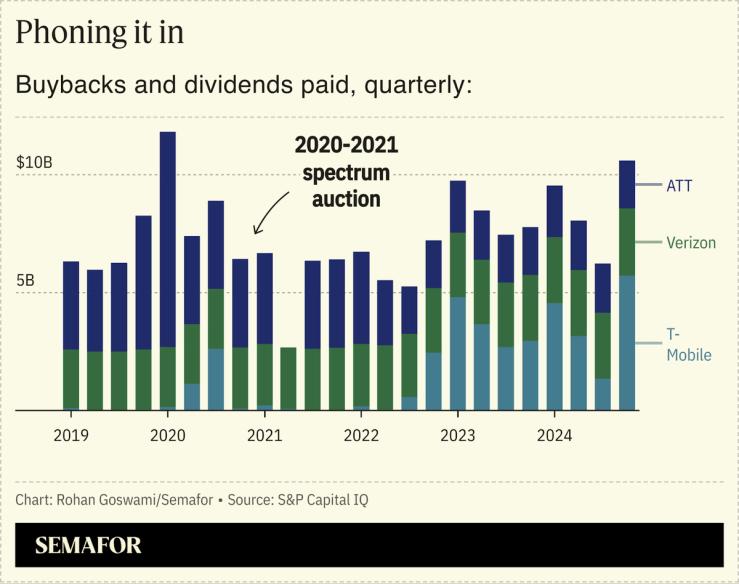

AT&T, Verizon, and T-Mobile spent a combined $81 billion at the FCC’s last auction, in 2021, and have borrowed heavily in recent years to pay for a broader spectrum buildout, begging patience from their shareholders. Now that stock buybacks and dividend growth have restarted, there’s little appetite among investors for a fresh round of capital spending.

The Congressional Budget Office has estimated that an auction could bring in $80 billion, according to several industry lobbyists familiar with the numbers. But that doesn’t account for the cost to the Defense Department to move its systems to a new wavelength, which a DoD official testified in 2023 could be more than $120 billion and take 20 years to pull off.