The Scene

MANASSAS, Va. — At a recent Prince William County meeting in Virginia, 71-year-old Elizabeth Martorana described living in a development area for Amazon, Microsoft, and Google data centers: “It’s like living in hell.”

Martorana’s retirement community sits within a few miles of more than 20 proposed data center parks under various stages of development, and is adjacent to a proposed AI campus expected to be the largest in the world once operational. Dump trucks crowd the roads, workers level trees, and the skyline is filled with a spaghetti of transmission lines. In the next town over, she said, she’s heard that the constant humming from the facilities is driving people crazy. Martorana told Semafor the buildout in her area is “the biggest preventable environmental and humanitarian travesty.”

In the high-stakes AI race, tech companies are straining to pay the hundreds of billions in capital expenditures and moving mountains to procure the elusive GPUs required to calculate the largest math equations humanity has ever seen. The biggest hurdle, though, may turn out to be the same obstacle that has long stymied the development of everything from housing to public transportation: the neighbors. Complaints revolve around the annoying noise permeating through nearby homes, schools, and parks. And residents just don’t want to look at the brightly lit, endlessly long, gray complexes that power products like ChatGPT, Claude, and Gemini — and they say are erasing the character of their neighborhoods.

In cities like Memphis, Tennessee, and Fayetteville, Georgia, local citizens are fighting to stop companies like xAI, Blackstone, and Equinix from breaking ground, potentially hindering the rapid expansion of compute power that companies need to meet AI demand and increase their models’ capabilities. These efforts are also colliding with ongoing debates across the country on permitting reform and the NIMBY versus YIMBY battles roiling communities. At the same time, the US is counting on the domestic buildout of data centers to maintain its technological edge against China, which is also racing to expand its AI infrastructure and has fewer regulatory or civic hurdles.

Northern Virginia, where Martorana lives, is where much of the US infrastructure buildout is taking place. It has an existing ecosystem for data centers, an AI-supportive governor, a robust fiber optic network, and available land. But some projects are running up against opposition from locals, with some of them suing the county and data center firms — including Blackstone-owned QTS Realty Trust and Compass Datacenters — over the expansion. They are also voting tech sympathizers out of official positions and protesting nearly every new facility during town hall meetings. Locals are hounding companies to make their existing data centers quieter and better hidden.

The outcry hasn’t sent companies packing, but it has slowed the full-steam-ahead approach big tech has benefited from in recent years. Among the biggest setbacks in the state are the $26 billion QTS and Compass project tied up in court, and a $12 billion campus by Culpeper Acquisitions that has been delayed.

The AI companies say they are trying to be good neighbors. They have made improvements to their facilities, donated to community organizations, sponsored local job training programs, and built parks. Amazon alone has pumped $75 billion into Northern Virginia since 2011, adding $24 billion to the state’s gross domestic product in that time, according to the company.

“We connect and listen to residents and local leaders by taking their feedback and incorporating that input directly into our development and operational processes to improve our data center community presence,” Kevin Miller, Amazon Web Services’ vice president of global data centers, told Semafor.

But so far, those actions haven’t appeased Martorana or many others.

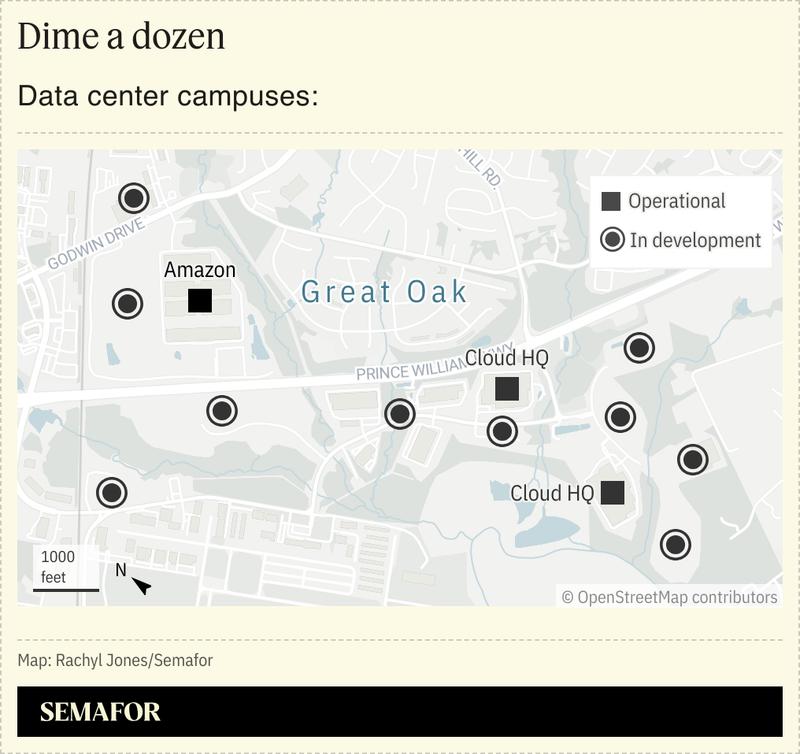

In one case, residents of a Manassas neighborhood called Great Oak complained about the constant buzzing coming from four nearby Amazon data center buildings — and specifically, from the 400 fans across their roofs that cool the servers inside, according to Dale Browne, who led the neighborhood’s homeowners association at that time. Amazon replaced the fans in 2023, Browne said, costing roughly $40 million by his calculations. (Amazon wouldn’t confirm the details.)

“Our engineers designed and implemented solutions that residents confirm have reduced sound levels, and those reductions have been validated by independent acoustic experts,” Miller said.

The updates reduced the tech campus’ noise output but created a new problem that has residents grumbling: The changes lowered the pitch of the sound, which now sends picture frames and dishes rattling in nearby homes, Browne said.

He and others are now working to change the county’s noise ordinance so Amazon is no longer in compliance and must take further action. Great Oak “was a wonderful place,” said Browne, who has lived in the neighborhood for 31 years. “It’s being destroyed.”

Know More

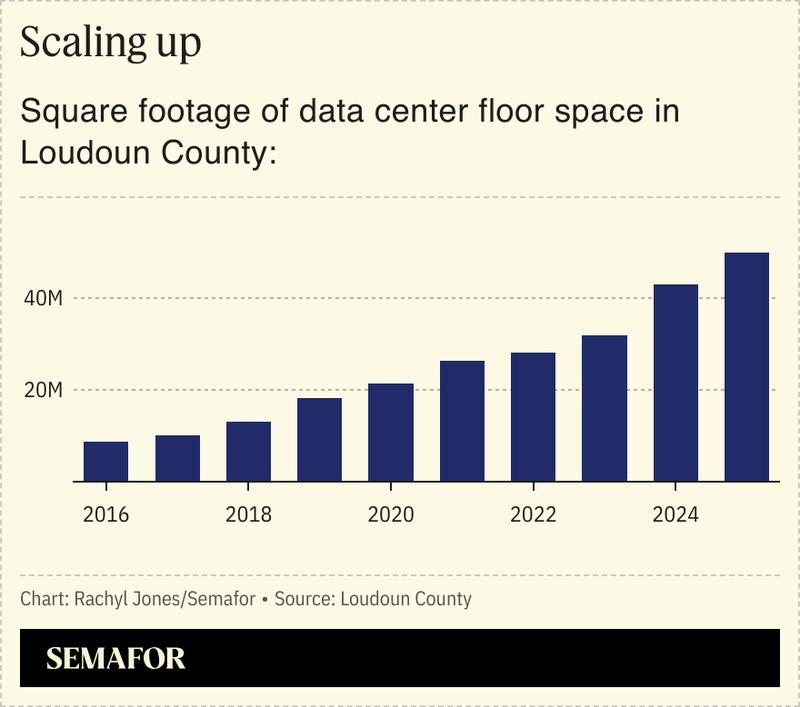

In Loudoun County, 45 miles from the nation’s capital, operational data centers and those in development span roughly 50 million square feet — about 1,150 acres. Nearby Prince William County, known for its Civil War history and for the Marine base in Quantico, doesn’t publicize an official count. Bill Wright, who lives in a neighborhood adjacent to a proposed data center campus, estimates it has 10 million square feet of operational data centers and 90 million more square feet planned based on public property documents.

Residents who spoke with Semafor, about half of whom are retirees, weren’t ideologically opposed to data centers — only the issues they cause when they’re placed so close to homes and schools.

“We bought [our home] near farmland, and what was once scenic is now completely surrounded by data centers,” said Ben Keethler, who lives in Ashburn, Virginia.

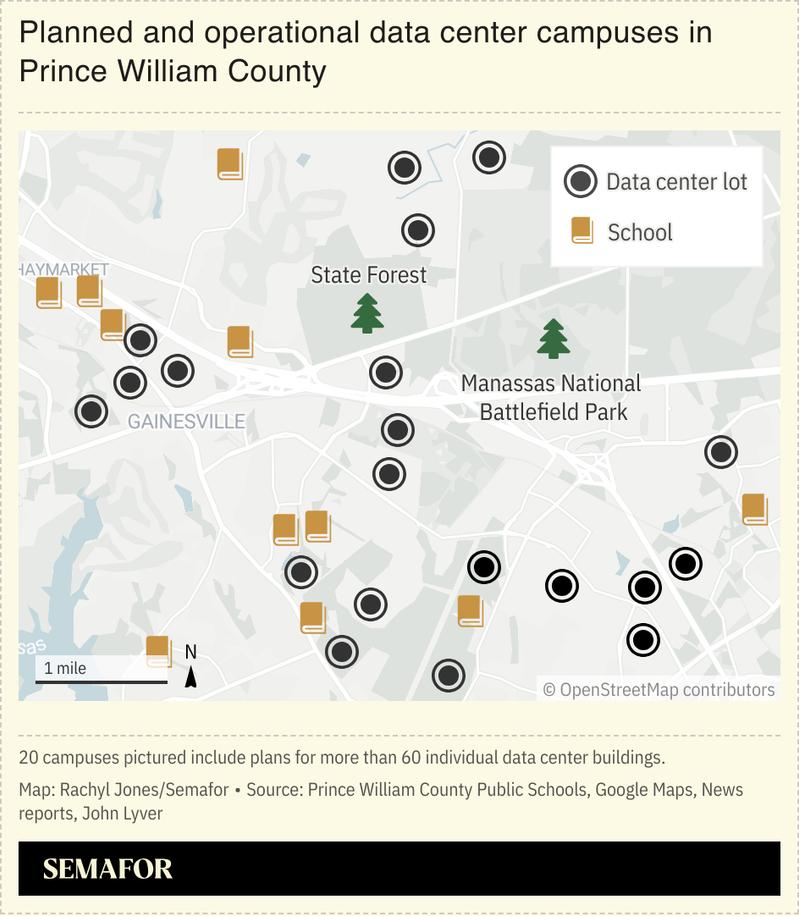

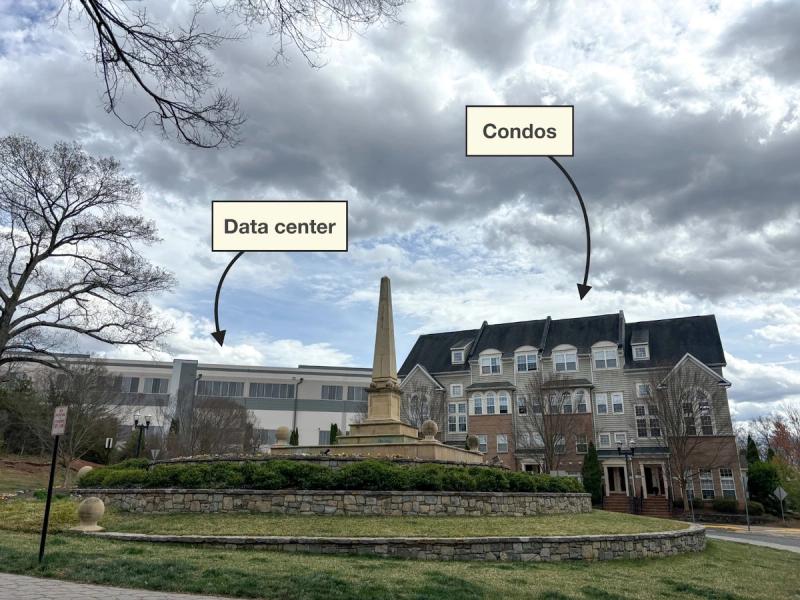

Across Northern Virginia, existing facilities — and sites that have been proposed or approved for construction — border schools, parks, cemeteries, homes, and Manassas National Battlefield Park, where two Civil War battles occurred.

Prince William County has a number of campuses in development that shouldn’t have been approved, according to Deshundra Jefferson, chair of the county’s board of supervisors. “Data centers had a lot of leeway” under the previous chairperson, she told Semafor.

In seven years, the county’s board has never rejected a data center application. While those years include Jefferson’s administration, she said her board has taken a stricter approach to making sure facilities aren’t too close to residential areas. That “put a stop to a number of bad applications,” she said. “And now that we’re talking about sensible guardrails, a number of them are balking at it.”

Ann Wheeler, who preceded Jefferson as chairperson, disputed the “leeway” and said that if the data centers hadn’t been approved, in many locations, townhomes or shopping centers would’ve been built instead. And the tax revenue brought in by the AI buildout — expected to be $364 million next year — has helped fund schools, social services, a new mental health center, roads, and parks. Data centers also support 74,000 jobs in the state, most of which are in construction.

Power Struggle

While the centers’ noise and locations are the primary complaints from residents now, tomorrow’s concerns revolve around energy.

The growing footprint of data centers in Northern Virginia means utility companies must expand capacity to serve them at a cost that will take decades to recover, according to a report by a nonpartisan state advisory agency. While data centers are currently paying their fair share of energy costs, consumers can expect higher bills in the future, the report said — both because of increased energy prices and because they’ll be shouldering the expense of building new infrastructure.

By 2040, a Virginia household consuming an average amount of energy could pay an extra $400 a year, according to the report. However, Loudoun County, a data center-heavy area, says the revenue from its facilities has helped lower residents’ property taxes. As a result, some households may see their tax benefits offset — or even outweigh — their increased energy costs.

“Where we require specific infrastructure to meet our needs (such as new substations), we work to make sure that we’re covering those costs and that they aren’t being passed on to other ratepayers,” Amazon’s Miller said.

Dominion Energy, which serves the area, has proposed to regulators raising energy rates for data centers more sharply than residential rates. If approved, large customers — which include data centers — would see an 18.5% price hike by Jan. 2027, compared to residents’ 15% increase. The company is also trying to require data centers to sign 14-year agreements to pay for a set amount of power, even if they use less. “That will protect residential customers from paying for costs that belong to large customers,” spokesperson Aaron Ruby told Semafor.

Whether the state can actually build enough energy infrastructure is another question. Meeting even half of the demand spurred by data centers over the next 10 years will be “difficult,” even with growth in renewable and nuclear power, the state report found.

Dominion has a plan to produce 27 gigawatts of new power in the next 15 years — more than double what it generates today, Ruby said. “It’s a realistic and achievable plan, and we’re already well on our way,” he said.

Step Back

Virginia Gov. Glenn Youngkin has prioritized the buildout of data centers in the state. “We should continue to be the data center capital of the world and make sure Richmond is doing what is necessary to support that goal,” Youngkin said during his State of the Commonwealth address earlier this year. And in Richmond, tech companies and Dominion are among the strongest lobbying forces.

A dozen key players have hired 84 lobbyists in the state, 25 of whom work for Dominion, according to The Virginia Public Access Project (VPAP), a nonprofit that tracks campaign donations and lobbying efforts. Dominion routinely spends some of the most on lobbying in the state, and two years ago shelled out an unusually high $4 million, more than 10 times the amount of the next-highest spender.

Rachyl’s view

Drive through certain parts of Northern Virginia, and you’ll see the data centers are indeed sprawling. I stayed in Virginia for three days to report this story, but I hardly noticed the low buzzing of facilities near me, including from an Amazon data center campus less than a mile away from my hotel.

Locals are putting up a good fight — and the concessions they’ve gotten from tech companies have likely made small but meaningful improvements in their neighborhoods. And efforts like theirs epitomize what has become one of the Democratic Party’s central internal fights now, over an “abundance agenda” that would reshape decades of environmental protections and local power. But between pro-tech Republicans’ control of Virginia and the US, a shifting Democratic debate over local autonomy, and the financial power of the world’s biggest companies, the anti-data center locals appear to be losing more battles than they’re winning.

The lobbyists working against community organizations have been a “David and Goliath struggle,” said Josh Thomas, a delegate representing Gainesville, a town in Prince William County.

Energy and tech firms are also shoveling cash at the delegates who will have a say in their futures in Virginia. Since 2021, Dominion has donated $25 million to local campaigns, committees, and PACs, including $6.4 million in the most recent election cycle, according to VPAP.

“It’s been a tough environment,” said Jefferson, the Prince William County official. “There were a number of proposed bills that would have reined in data centers, and they were either rejected or watered down.”

Room for Disagreement

Resistance appears to be spreading, as national media covers the Virginians’ stories and as the anti-data center whisper network grows. Browne said he has been contacted by people around the country — in the suburbs of Columbus, Ohio, and in Peculiar, Missouri, for example — who are weighing letting data centers expand in their communities and want to hear his experience.

In August of last year, at the request of Peculiar locals, Browne posted in a city Facebook group about the noise problems in Great Oak. Two months later, Peculiar council members unanimously blocked a $1.5 billion data center bid by Diode Ventures.