The News

If you’re a parent, you’re probably worried about your children and screen time. You’ve probably seen headlines saying that young people’s mental health is suffering, that suicides and depression are way up, and that smartphones are responsible.

You might think: I don’t want to take risks with my kids’ mental health. If there’s even a chance that social media could be harming them, I don’t want to take that chance. Why not restrict my child’s screen time, or — at a societal level — impose legal limits on children’s access to social media? After all, it can’t hurt.

But it absolutely can hurt. The evidence on whether social media is harmful is ambiguous, and cutting teens off from social media means cutting them off from their friends. Before we talk about taking away teenagers’ phones or age-limiting social media, we need to be incredibly careful that we’re not doing more harm than good.

In this article:

Know More

First: Is there really a mental health crisis? It’s definitely true that more teenagers in several countries report symptoms of mental ill health than they did five or 10 years ago, Lucy Foulkes, an academic psychologist at Oxford University and author of the book What Mental Illness Really Is… (and what it isn’t), told me. “That’s a simple fact,” she said. “But the question is why.”

It could be simply that teens really are more depressed and anxious. Or it could be that mental illness is less stigmatized, so people are more willing to report it. A third possibility, she suggested, is that we “repeatedly tell teenagers that they’re an anxious generation,” so that they are more likely to think mild anxiety symptoms are a mental health problem. Her overall take is that the decline in teen mental health is “real but not straightforward.”

The next question is: Are smartphones causing it? “It would be foolish to ignore it as a possibility,” Foulkes noted. But there are lots of other possibilities: One in 10 teenage girls in the U.S. have missed school in the last 30 days because of fears of violence, and one in five say they’ve been the victim of sexual assault in the last year. Research by Andy Przybylski, a psychologist at the Oxford Internet Institute, and his colleagues into the mental health impacts of social media has found only evidence for very weak negative effects, and even some slight positive effects for moderate use. It may be that some individuals suffer badly even if the average teen doesn’t, but it’s hard to draw a picture of a societal crisis.

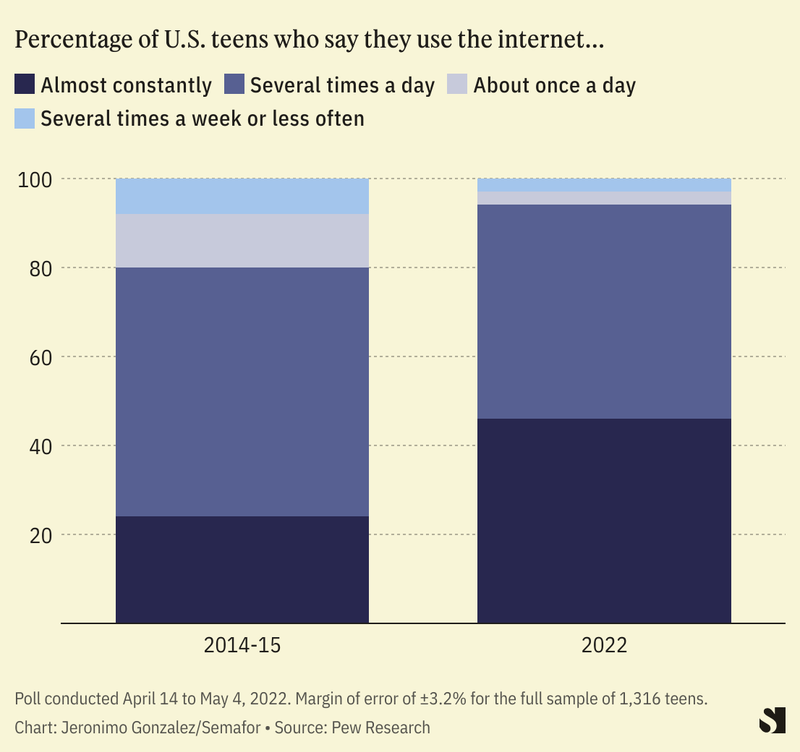

Even if smartphones are to blame, that raises the question of how. One possible mechanism for how social media has affected mental health is by reducing in-person contact, because everyone socializes online. But if that were true, the only policy response would be to stop everyone from accessing social media. If just one person were to stop, Foules said, “they’ll be worse off.”

Perhaps social media is driving people to catastrophize about their own mental health. Foulkes noted that Western societies largely started talking about reducing stigma and being aware of mental health around the start of the social-media era. But while those messages might have originated on social media, they’re society-wide now, propounded through mainstream media and even schools (my children learn about mental health awareness in elementary school). Taking the phone out of a teenager’s hand, or even banning all teenagers from using them, might not help.

Tom’s view

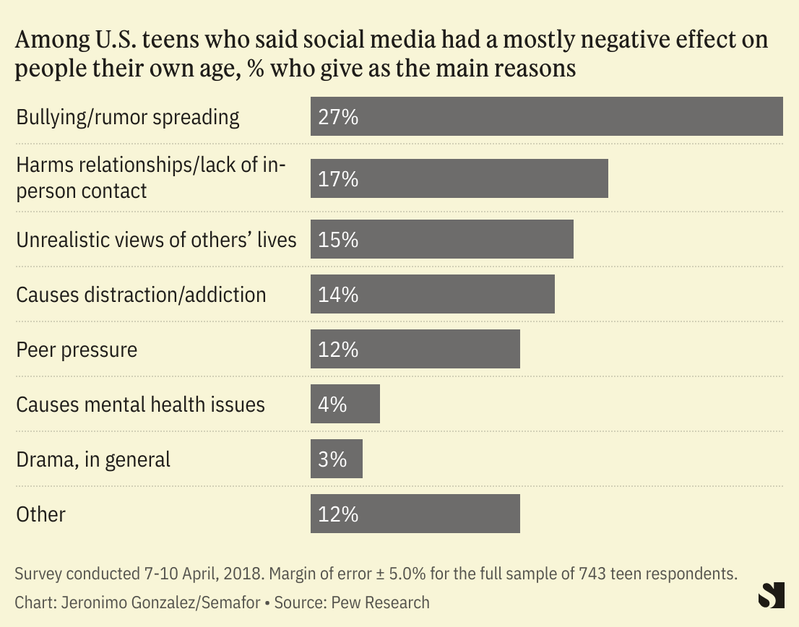

If young people are looking at Instagram and seeing images of other people’s unrealistically wonderful lives and it’s making them sad, or if they’re being bullied, perhaps putting the phone down could help. But we don’t know the mechanism by which they are becoming more sad, even if we accept (which I don’t, yet) that social media is the main driver of a real decline in mental health.

This is where you might invoke the precautionary principle. We don’t know that social media is causing it, but it might be, so why not limit it? I have a seven-year-old and a nine-year-old, so this conversation will apply to me in a very real way, soon.

Social media is the means through which teens socialize: There’s no putting the toothpaste back in the tube. If we take away a 13-year-old’s phone, we’re cutting them off from their peers. As Foulkes told me, being ostracized is terrible for mental health — that’s not ambiguous or contested like the impact of phones is. Deliberately ostracizing children in the name of mental health does not sound a good idea.

It’s not realistic anyway, she says. “Phones aren’t going to go away. This is the way teenagers interact now. We need to talk about how we can help them navigate that.”

Quotable

“Every time we have a mental health awareness week my spirits sink. We don’t need people to be more aware. We can’t deal with the ones who already are aware.”

— Simon Wessely, the first psychiatrist to become President of the U.K.’s Royal Society of Medicine.

Room for Disagreement

Jonathan Haidt, a social psychologist at New York University and perhaps the leading voice saying that social media is the driving force of a growing mental health crisis argues that most “correlational” studies — that is, those looking at real-world data — find that people, especially girls, who use social media more tend to have worse mental health. Correlational studies can’t be used to show causality, but he also says that experimental studies, which take two groups of people and give one access to social media, and which can show causality, also show this relationship.

Notable

- The psychologist Stuart Ritchie makes the case that the evidence is far weaker than Haidt claims, and that in particular experimental studies are very ambiguous and, for statistical reasons, difficult to draw conclusions from. The statistician Aaron Brown agrees with Ritchie.