The Facts

Brookfield once embodied Wall Street’s love affair with commercial real estate coming out of the 2008 crash, when there were bargains aplenty and cheap debt on offer.

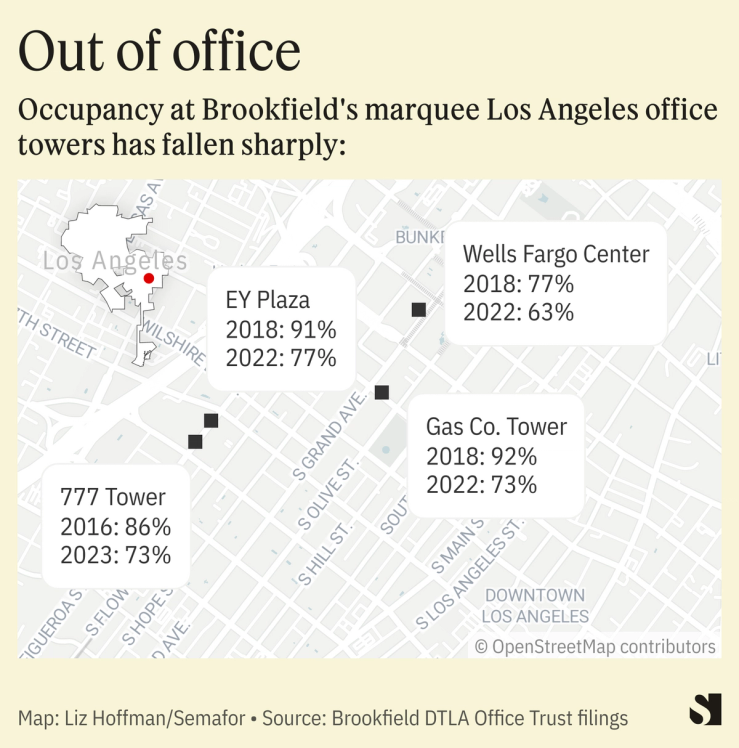

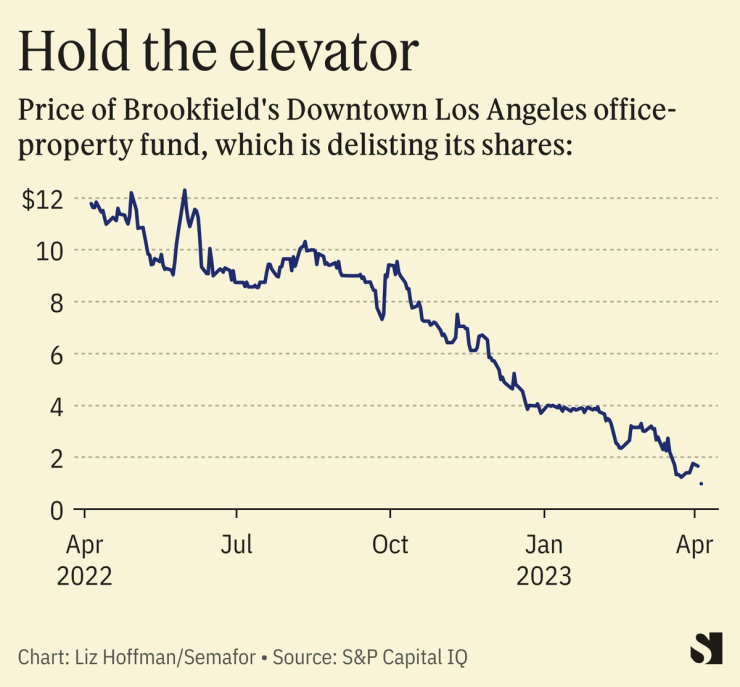

But earlier this year, Brookfield defaulted on two of its signature properties in downtown L.A. after interest rates rose sharply and leases rolled off, unrenewed. Shares of the listed fund it used to acquire those properties and five others in the city fell from $12 a year ago to just over $1 this spring and are being delisted from the New York Stock Exchange.

Investment firms that charged into commercial real estate, confident of their ability to keep raising rents and refinancing their debt at low rates, are handing the keys back to the bank.

Goldman Sachs is stuck with $200 million of debt backed by San Francisco apartment buildings after two investors, hedge fund Baupost and real-estate firm Veritas, walked away. The bank is fielding bids of less than 90 cents on the dollar for the debt, people familiar with the matter said.

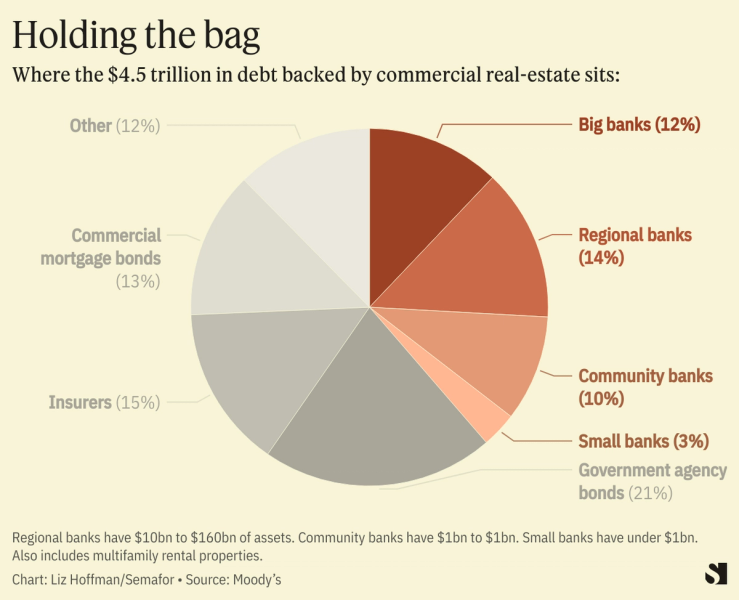

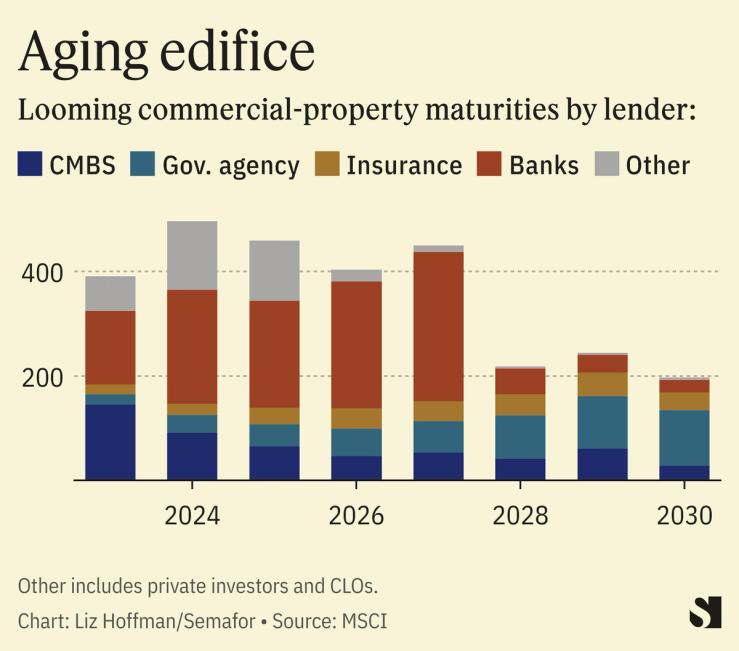

Some $900 billion of office-tower and apartment-building debt will come due by the end of 2024, according to MSCI. Almost half of it sits on the balance sheets of U.S. banks, which have emerged, reeling, from the recent turmoil.

Banks holding impaired loans will have to decide whether to cut borrowers a break or become the proud new owner of an office tower. Being too generous, though, creates paper losses and lays the same tinder that ignited at Silicon Valley Bank.

Know More

Blackstone rattled European debt markets by bailing on a €531 million loan backed by Finnish offices and stores. An arm of PIMCO, the giant West Coast money manager, defaulted in February on $1.7 billion of debt backed by seven office buildings in New York and San Francisco. (A problem tenant included Twitter, which PIMCO has sued for $136,260 in unpaid rent.)

These defaults mostly aren’t acts of desperation by a weak player but rather cool-eyed assessments by seasoned investors. Even those with the deepest pockets are being forced to pick winners and losers from within their own portfolios.

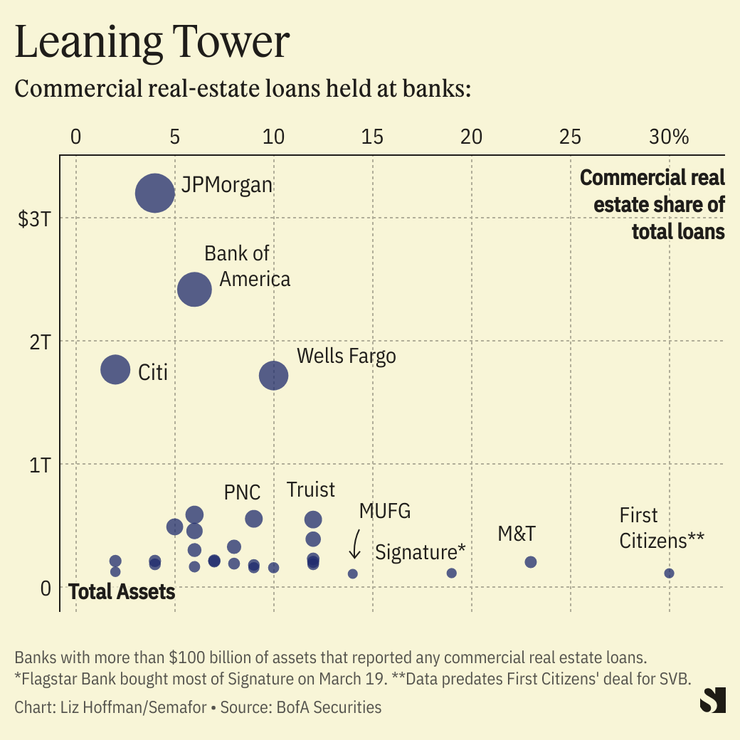

America’s biggest banks hold $550 billion in commercial property debt, according to the Mortgage Bankers Association. Another $1.2 trillion is sitting at smaller banks — 15% of their total assets, at a time when depositors are pulling their money, or at least being cautious.

Step Back

Landlords borrowed cheaply over the past decade, but those rate lock-ups are expiring, bringing higher debt payments.

And three years into the hybrid-work experiment, companies are shrinking their footprints and upgrading to shinier buildings when their leases expire. That space is going unfilled or re-rented at lower rents.

That leaves property owners facing a choice: Pony up more money to meet higher interest rates and needed renovations, or simply hand the keys back to lenders. It’s a big-money version of what happened in 2008, when underwater homeowners simply stopped paying, daring the bank to repossess.

Just look at Brookfield’s L.A. holdings. Gas Company Tower, a 1.4 million-square-foot, 54-story office building in the Bunker Hill neighborhood that Brookfield bought in 2013, was 92% leased in 2018 but just 73% leased at the end of last year. The same goes for its other properties in the city’s financial district:

Liz’s view

My conversations over the past few weeks with bankers and investors have centered on a single question: whether the regional-banking turmoil is over.

I think yes, but with a major caveat. Banks take different kinds of risks when they make a loan. One is the risk that interest rates will either quickly rise (those loans get less valuable) or fall (all your borrowers will refinance at lower rates and there goes your profits). Another is credit risk: Will the people you’ve lent money to pay it back?

The concern now is that the recent focus on rate risk might be overlooking the fact that the underlying loans are bad, or at least much worse than we thought.

Foul-ups like those that took down Silicon Valley Bank are simple math problems to solve and avoid, and increasingly so as the Fed gives a clearer map of where it’s heading on interest rates. They are a problem at the bank level: SVB made bad bets and underestimated the loyalty of its depositors, and so it went out of business.

But problems on the borrower side of the trade are thornier. They only become clear as trouble spots emerge in the economy and assumptions that underpinned investments made in better times are proven overly optimistic.

Brookfield, when it barreled into Los Angeles in the early 2010s, assumed it would be able to command higher rents going forward, especially as its growing footprint boosted its negotiating muscle with tenants. When it refinanced the Gas Company Tower two years ago, the deal terms assumed cash flow of $29 million on total rents of $58 million, according to investor documents seen by Semafor.

Through the first nine months of 2022, the building was on pace for just $21 million in cash and $51 million in rents.

Room for Disagreement

Investors (and reporters) have a tendency to look for the next crisis in the ashes of the last one, and 2008 looms large in everyone’s memory.

Real estate today has some of the ingredients that proved disastrous last time — specifically loans made on the assumption that the good times would continue. But it’s missing a key ingredient: mountains of debt.

Banks and even their pseudo-rivals, private credit funds, aren’t nearly as rickety as they were in the mid-2000s. The biggest banks held as much as $30 in investments for every dollar of shareholder equity. Today they hold about $10 for each dollar of equity. Less debt means losses are minimized and more contained.

One other counterpoint: Blackstone just raised $30.4 billion for its new real-estate fund, the largest ever.

Notable

- “Office towers aren’t doomed — just the mediocre ones,” from Insider.

- Things are no better in Europe. The FT’s big read on cracks in the continent’s property market.

- “Revenge travel” boosts hotels, but malls are a mess, a Moody’s analyst tells Yahoo.