The Signal Interview

AstraZeneca’s CEO, a French-born Australian running an Anglo-Swedish company, is betting $50 billion on a strategy of making the US its largest market — while also pouring $15 billion into China.

Each of the time zones Pascal Soriot operates in has offered vivid reminders of the delicate balancing act global business leaders must perform as the world economy transforms around them. Soriot caused angst in Westminster after retreating from planned investments at two UK sites, and after he decided to secure a full US listing for the FTSE-100’s largest company. Yet he still had a front-row seat for Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s recent trip to China.

The investments he announced in Beijing last month came just two years after Chinese authorities detained his most senior executive in the country. And when he stood in the Oval Office to announce AstraZeneca’s US expansion plans and an agreement to cut some drug prices, it was only after President Donald Trump threatened punishing tariffs on its imports.

Soriot has played this geopolitical game better than many in his industry, transforming AstraZeneca’s global reach as well as its sales, reputation, and pipeline of promising drugs. After 14 years in charge of the $320 billion company, he appears in no hurry to step down, setting his sights on a “2030 ambition” of lifting annual revenues to $80 billion, from $28 billion in 2012.

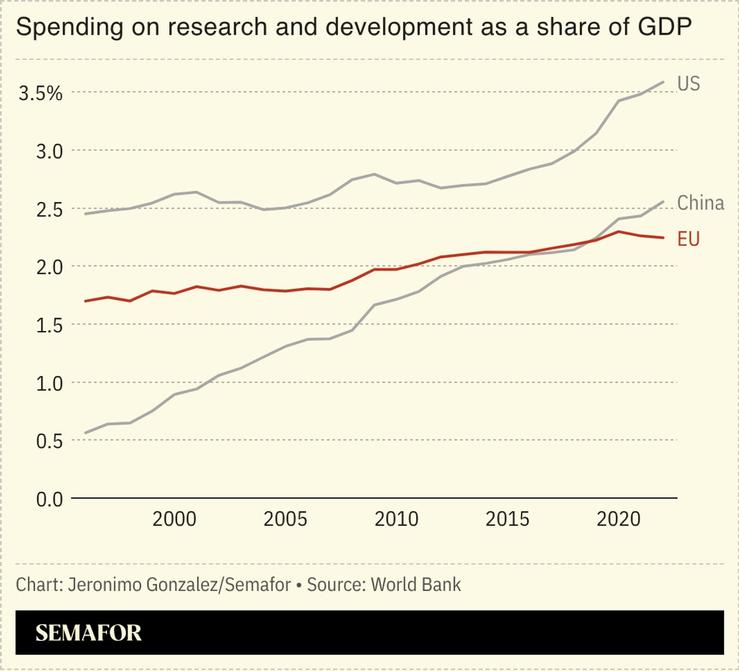

“These days, companies may have a domicile, but domicile has limited meaningfulness,” Soriot says in an interview in London: “We truly are global… and I think companies really have a formidable role to play, connecting the world.” But that world is changing, he adds, with the rise of two new science superpowers.

The investment choices that can shape an industry

Inside any company, you need “a sufficient amount of tension so people understand the need to perform,” Soriot says — not destructive competition or silos, but an understanding that the head office will back projects that move the needle, and turn down those that don’t.

“It’s the same for countries,” he adds. Asked whether his decision to halt a planned £200 million expansion of its Cambridge research site was a way of gaining leverage over a UK government from which AstraZeneca wanted more financial support, he acknowledges that “some people read it that way.”

But the bigger rationale, he says, was that his company needed to prioritize investment in the US — first because it needed to expand its manufacturing capacity there, “but secondly, of course, because the US administration asked us to invest or face tariffs.”

“You’ve got to make choices,” Soriot says, and his company has opted to invest where there is both a strong base of scientific talent and a market that rewards its innovation. His argument is that Europe has “destroyed” its leadership in biopharmaceuticals and put its “health sovereignty” at risk by focusing more on the cost of the industry’s products than on its strategic importance.

“We have been telling governments in Europe, not only the UK, for a long time, you need to create an environment to attract investments. And if nothing changes, at some point, you say, ‘Well, we’ve tried hard. Now we have to do what’s right for the company long-term.’”

AstraZeneca has needed to become more adept at dealing with different governments, Soriot says. It engaged early with members of the second Trump administration, both “to understand how to help them achieve their goals” and to argue that they should not “destroy the industry,” as he thinks Europe has done.

As his company grows, he explains, “we have to make sure that we help shape the industry.”

Competing with China when ‘they don’t need us any more’

Soriot’s generation of leaders grew up in the era of globalization, but must now navigate an interconnected world economy that plays by different rules. He cites his own experience: He’d never left France before age 19, but later learned the value of international cooperation by working in New Zealand, Australia, Japan, the US, Switzerland, and the UK.

“For me, globalization is about collaboration and competition. It’s not about giving away what you’ve got,” he says.

There is a harder message in that observation, particularly for Europe and the UK. Countries “cannot be naive in this competition,” he warns. Governments, like companies, must identify what their assets are and build on them: “You have to play to your strengths and invest in those. You can’t just say, OK, I’m good at this and then spend no money. Doesn’t work.”

Soriot says the “animal spirits” that drive the US economy remind him of his French parents’ desire to build a better life for themselves and their children after World War II. But he sees a particular danger that Europeans fall into the “trap” of believing that any victory for China is the result of the country “not playing by the book.”

That perception is not correct, he says. “It’s not like we invest in China and Chinese companies basically steal what we do. I mean, they don’t need us anymore. We partner with them because they have great innovation, great technologies and great scientists.”

If Europe does not learn to collaborate with China while competing with it, he warns, “we’re going to lose.” AstraZeneca, he adds, has spent the last few years training its Chinese teams to take the lead of global projects to ensure that they learn to work with the entire company — and teach it how to develop products faster.

Soriot rejects the idea that his investments in China risk accelerating the disruption of the science base in the UK and Europe. “If we don’t do it, someone else is going to do it, especially Chinese companies,” he said. And if the pharma industry’s traditional powerhouses don’t learn to compete with Chinese peers that are setting the pace on AI and robotics, “those companies will basically replace us.”

Building strategy around a mission, a plan, and historic strengths

Just as Soriot tells UK ministers to focus on the country’s strengths in life sciences and artificial intelligence, he has built AstraZeneca’s growth strategy around its historic strengths in areas like treatments for cardiovascular and respiratory diseases. But when he arrived from Roche to take up the CEO role in 2012, he discovered these “were falling apart.” In oncology, he recalls, “we had only a handful of people who knew what they were doing.”

The temptation might have been to “break everything, fire everybody, and start again,” but that was not Soriot’s approach. “Even if a company is going through a difficult time, you have to evolve it over time,” he says.

There were three steps to overcoming the skepticism that greeted his arrival, Soriot says: setting out a clear “shared ambition” of what kind of company AstraZeneca could become; narrowing its focus on a few priorities; and having a plan that was credible enough to convince people that he could deliver.

Once that framework is set, he says, “you have to take risks”. When he sold non-core assets to reinvest the proceeds in research and development, for example, investors wondered why he was shedding profit-making businesses before the other bets he was placing had paid out. “If R&D had not delivered, then we would have been done,” he reflects. He felt the pressure most strongly in 2013 and 2014, he says, but it was not until 2017 that his strategy started to produce “green shoots.”

How ‘casual intensity’ can direct the energy of an organization

Under Soriot’s leadership, AstraZeneca’s hit rate for taking drugs from pre-clinical stage to final development has far outstripped the industry average. It has more than 100 Phase III trials running, and expects readouts from at least 20 of them in 2026, making for a pipeline that Citi analysts have called the strongest in the sector.

Soriot, who earlier this month announced a robust 8% increase in revenues for 2025, calls its current performance “a validation of believing in science and believing in talented people.” But he is wary of claiming victory, he says, because success breeds bureaucracy and complacency.

“When you’re about to crash and burn, you realize you have to take risks, and everybody does. But when you’re successful, it’s very tempting to say, ‘OK, we carry on doing what we’re doing, and not take risks any more and relax,’” he says. “You have to continuously make sure people understand the need to innovate and perform.”

Soriot has described his leadership style as “casual intensity.” He has a reputation for delivering such messages in person, and is known to call up scientists several layers below him in the 130,000-person company to understand the molecules that he is being asked to invest in. The hands-on approach is appropriate when some drug studies can cost more than a manufacturing plant, he says, but it is also a way for him to keep testing his strategic priorities, and to keep an eye on talent.

When a retired CEO asked recently how Soriot kept going at the age of 66, his answer was curiosity and the knowledge that he was working with great people who are making a difference. “But you cannot make a difference if you’re just flying at 30,000 feet,” he says. “I really believe you need to be able to understand the broad picture and where you need to prioritize, but also understand enough of the details so that you can actually help direct the energy of the organization.”

Asking questions of people at all levels of the company ensures that a CEO keeps learning, but it also helps him identify “who is on top of their game, and who is not,” Soriot says. “People tell you, ‘I pick talent.’ But the question is, how do you pick talent? You can’t pick talent just talking to people [over] coffee.”

Notable

- Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk’s GLP-1 drugs have defined the weight management drug market, but AstraZeneca last month struck a deal with China’s CSPC to license experimental drugs for obesity and other weight-related conditions. The agreement, worth $1.2 billion to $17.3 billion depending on certain milestones being met, follows AstraZeneca’s licensing of an experimental weight-loss pill from China’s Eccogene.