As gold prices soar, Ghana’s leaders have a rare opportunity to solve the country’s long-standing challenge: To transform the country’s vast gold reserves from an occasional foreign exchange windfall into a strategic development lever.

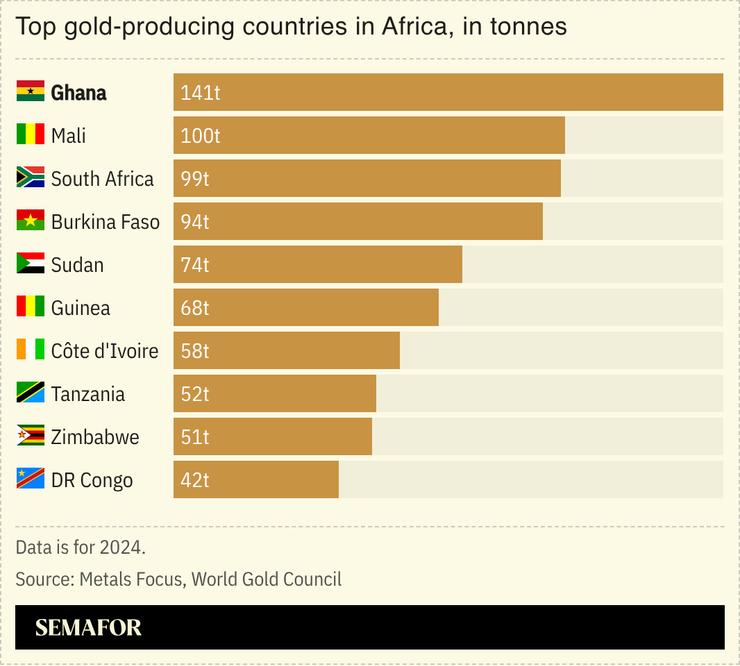

As the world’s sixth-largest producer, Ghana sits in a position most countries would envy. Record prices have catapulted gold to nearly 70% of all export earnings, amounting to roughly $21 billion last year. That represents nearly a fifth of GDP, but still leaves Ghana far from the upper-middle income status it craves.

Turning gold into a strategic lever for growth has been the country’s perennial challenge, one that policymakers have consistently framed as the pursuit of a”value addition.” But value addition has been narrowly understood as incremental refining — turning raw gold into bullion, or gold refined to 99.5%. This framing mirrors the wider African commodity narrative, in which the continent exports raw materials while capturing only a sliver of global value.

But gold is a more nuanced case than oil, cocoa, or copper. Most gold already leaves the continent relatively well refined. That means the reward for further refinement often amounts to only about 2% to 4% markups for refineries. Gold refineries in Africa are thus operating in a brutally efficient global industry where most larger refineries in countries like Australia operate on typical net profit margins of between 0.05% and 0.5%.

It’s no wonder that over the years Ghana has seen at least half a dozen major refineries end up idle, including a recent government-backed one mired in controversy, as none have been able to operate sustainably.

The simple truth is that Ghana has repeatedly mistaken refining for “value transformation.” But refinement is not where meaningful value lies.

Refined gold is still just bullion. If bullion sits in bank vaults, it earns no interest. Nearly half of all gold in the world, however, is used for jewellery, which on average generates 300% more value than bullion. Nearly 8% goes into equally knowledge-intensive electronics and medical technologies, which are even more valuable.

Ghana should learn from countries such as Thailand and the Philippines, which have spent decades building a knowledge ecosystem to promote just this kind of value transformation. Both Southeast Asian nations have prioritized public-private partnerships in which the state invests in skills, design schools, certification, and technical capacity, while private firms focus on branding, market access, and consumer trust.

By contrast, Ghana has failed to invest in such an ecosystem, while it has backed refineries and operated a state-owned jewellery company. For years, the state-owned jeweler struggled to secure even two kilograms of gold a month for production, while the country exported 2,500 to 4,000 kilograms monthly in raw form. Recent regulations have even placed private firms in direct competition with a state entity.

It is shocking that despite 130 years of industrial gold mining, Ghana today has no industry-standard gold assaying laboratory, such that foreign specialists always have the last word on the purity of Ghanaian gold. This is what happens when a country doesn’t prioritize its knowledge-ecosystem highly enough.

Ghana must stop confusing control with progress, and refinement with transformation. Political imagination must now be matched by skilled policy execution.

Bright Simons is Honorary Vice President at IMANI, a think tank in Accra, and a visiting senior fellow at ODI Global, a think tank in London.